AUCTORES

Globalize your Research

Review Article | DOI: https://doi.org/10.31579/2637-8892/236

Psychologist in private practice. Doctor in Psychology, Psychologist Specialist in Clinical Psychology, Doctor in Philosophy

*Corresponding Author: Antonio Duro Martín, anduma@cop.es; Associate Professor, Universidad Rey Juan Carlos (URJC), Madrid, Spain (2003-2013); Collaborating Associate Professor Doctor, Universidad Pontificia de Comillas (UPCO), Madrid, Spain (2010-2011).

Citation: Antonio Duro Martín, (2023), Re-Print: Self-Esteem: Update and Maintenance. A Theoretical Model with Therapy Applications, Psychology and Mental Health Care, 7(7): DOI:10.31579/2637-8892/236

1 This is the English version of the following article: Duro, A. (2021). Autoestima: actualización y mantenimiento. Un modelo teórico con aplicaciones en terapia. Clínica Contemporánea, 12 (3), Articulo e23, 1-20. https://doi.org/10.5093/cc2021a16

Copyright: © 2023, Antonio Duro Martín. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received: 03 November 2023 | Accepted: 13 November 2023 | Published: 21 November 2023

Keywords: self-esteem; low self-esteem; model; theory; therapy; self-concept

Conceptualizing self-esteem as the result of the comparation between two schemas of the self, model-self and perceived-self (self-concept), a systemic, integrated, and analytic model is proposed to explain how that construct is updated and maintained in real time. Its theoretical structure includes elements of two types: components -situational antecedents, representations and mental states-, and cognitive processes -deduction, interpretation, and attribution. Within its operation stand out the self-esteem occasions -situational triggers-, the role plaid by the model-self as a principle to derive various blocks of information, the final experiences produced by self-esteem, and processes of feedback to correct inputs to the system. The model is based on research results in this field and is consistent whit other various psychological theories and constructs. Its clinical applications in psychopathology and psychotherapy are outlined, especially the possibility of developing its own therapy.

The relevance of self-esteem is revealed by the number of academic publications that it has been generating. There are more than twelve thousand references for “self-esteem” and more than three hundred and fifty for the combination “self-esteem + low,” as search terms for the “title” field in the PsycINFO database, as of July 2020. Qualitatively, its importance is revealed by the multitude of theories about this construct (Maxwell & Bachkirova, 2010). There are also recent meta-analyses that link it with sexual orientation (Bridge et al., 2019), social relationships (Harris and Orth, 2020), status identity (Ryeng et al., 2013), patient treatment anorexics (Kastner et al., 2019) and the differences between men and women (Zuckerman et al., 2016); and meta-analyses that study their development during the life cycle (Orth et al., 2018) and changes from childhood (Huang, 2010).

On the other hand, low self-esteem and associated psychopathology extends throughout the population, affecting children (Wanders et al., 2008), adolescents (Taylor and Montgomery, 2007) and adults (Steiger et al., 2015). It presents comorbidity with anxiety (Pyszczynski et al., 2004) and depression (Steiger et al., 2015), eating disorders (Chang 2020; Shiina et al., 2005), personality (Jacob et al., 2010), and psychoses (Hall & Tarrier, 2003). Hence the variety of therapies developed from classic and latest generation clinical approaches.

However, such an abundance of research and therapies suffers from excessive fragmentation, giving the impression that they all refer to the same underlying factors that, however, remain implicit. Asking ourselves about this problem, the purpose of this work is to propose an integrated model of self-esteem, of a systemic nature and with a very analytical description of processes - in order to enable its subsequent clinical application -, where the antecedents, representations and constituent mental states are made explicit in their updating and maintenance, basing its theoretical structure on previous empirical results.

Before exposing the model, we will specify its material object and stage of development. It is a cognitive-behavioral model of a factual or interpreted nature to explain the updating and maintenance of self-esteem; It is not a model to explain self-esteem. It is in a preliminary phase of theoretical construction and, at present, offers a general definition (of a more abstract nature) of its components and processes, as well as a sequence of non-arbitrary relationships between them. Despite its current heuristic nature, the model complies, as will be verified, with those methodological criteria required in a preliminary theoretical phase (Bunge, 2000), namely: conceptual unity and empirical interpretability (semantic criteria); as well as external consistency, scope, depth and unifying capacity (gnoseological criteria), thereby making possible its future formalization in subsequent phases of theoretical construction.

In its current stage, the model does not define the concrete content of its components - situational antecedents, representations, consequent mental states - which it adopts as basic postulates (the premises in a pre-axiomatic phase of theoretical construction) to establish the object of study. In fact, such contents are peripheral postulates because their change or modification would not affect the core of the model (Bunge, 2000). In particular, although the model recognizes and assumes the existence of contents, dimensions or factors of self-esteem, in principle it does not commit to any of them, which would only have a methodological character of primitives or foundations at the base of its theoretical body. On the other hand, the references cited in the present study have been taken solely and exclusively as illustrative cases that have been taken into account in the formation of the model, they are remarkably diverse and sometimes with a certain conceptual distance in accordance with our unifying theoretical intention. Furthermore, given the novelty (gnoseological criterion) of our approach, except error, there are no or we have not found direct antecedents to its structure.

Finally, we say that the model is “systemic” in a double sense. With this word we refer to both its systematic conceptual structure with internal validity (Bunge, 2000) and its functioning as a system, specifically a system with feedback. Keep in mind that this type of system covers various self-regulatory functions in man (von Bertalanffy, 1989).

Self-esteem is defined as a system open to the interactions of the person with their environment and self-regulated, whose updating and maintenance tend to optimize the mental state of the individual. If the system becomes destabilized, in the case of low self-esteem, it will then try to restore itself by modifying its component elements. A dysfunction in this process for one reason or another will cause subjective discomfort and probable psychopathology.

The model adheres to the basic theoretical foundations (Bunge, 2000), being cognitive in nature since its conceptual structure includes both mental representations (Pylyshyn, 1980) and cognitive processes (Bourne et al., 1979; Broadbent, 1984; Fodor, 1983; Lachman et al., 1979; Schank, 1984), although it also includes behaviors in response to the environment. Its operation is consistent with the theories on resource conservation (Hobfoll, 1989, 2001): self-esteem as a resource; working memory (Cowan, 2000): self-critical rumination in low self-esteem (Kolubinski et al., 2017) that wastes resources; self-efficacy (Bandura, 1986): incompetence lowers self-esteem; and interpersonal acceptance and rejection (Rohner and Carrasco, 2014): social approval reinforces self-esteem; and it is compatible with the self-regulatory executive function model (Wells, 2000; Wells and Matthews, 1994, 1996): self-esteem as an essential piece in personal self-regulation. Its articulation with these other constructs in an ascending and descending sense reinforces its validity, in accordance with Bunge (1974). For the rest, its components are linked to the material object of the current psychology of the mind: schemes of the self -personal identity (Metzinger, 2009); mental states -self-awareness (Noë, 2009); personal project -intentionality (Dennett, 1989); and feedback loop -mental causation (Varela et al., 2016).

Self-esteem is defined as the result of a person's prior assessment of himself, which implies the following:

(a) Since it is a valuation, the pre-existence of two previous terms is necessary that make it possible and allow them to be compared to each other to estimate their differences or similarities, namely: (i) one's own self, or self-concept, as it is perceived by the person at a certain moment, and which we will call “perceived-self”; and (ii) another self that the person takes as a reference or archetype of their perceived-self, and which we will call “model-self.” Actually, in this assessment process the perceived-self is compared with the model-self, both being representations or mental schemes. Therefore, self-esteem is equal to the value, merit or demerit, that someone grants to themselves after having compared both schemes. The greater the similarity between them, the greater the self-esteem, and vice versa.

(b) As it is a self-assessment, the person gets involved and involves himself in it, attributing responsibility for its result.

Although self-esteem corresponds to the individual, however, its origin and maintenance are psychosocial in nature. It is transmitted intergenerationally (Steiger et al., 2015), shaping its development during childhood and adolescence from multiple characteristics of the family environment (Krauss et al., 2019). Johnson (2010) defends its evolution in two phases, a basic self-esteem, of a more affective nature, constituted first; and another subsequent self-esteem that one must earn by one's performance. Regarding influences from the family environment, a relationship has been found between certain parental actions and the psychosocial development of children (Fuentes et al., 2015; Gallarin et al., 2021). Also, the family dimension of the self could be explained from the parental impact (Martinez et al., 2021).

Being the result of the person-environment interaction, self-esteem fits between antecedents and consequents, resulting from determined causes and producing specific effects. Its full immersion within a broad constellation of factors reveals it as an integral part of a larger and more complex dynamic system, alluding to its forced plasticity. In summary, its essential qualities are: (a) it is part of the person-environment interaction system; (b) it is continually updated by being contingent with the above, (c) it is a consequence of a previous comparison process, (d) it generates particular effects, connected to a feedback process, and (e) its structure, that is, its components and processes, constitutes a system in itself.

For its part, the model-self also exhibits its own profile during self-assessment: (a) imperative character: unavoidable model; (b) rigidity: non-modellable model; (c) contingency: the potential benefits of the model are not guaranteed, and (d) immediacy: automatically activates the processing cycle.

Without impediment of environmental influences, it is possible for a person to deliberately adopt a model-self as a personal project, as a commitment to himself to be and behave in a certain way, an option that equates the human mind to a propositional mechanism, a matter that concerns the intentionality of our actions, a question already belonging to the field of philosophy of mind (Dennett, 1989; Metzinger, 2009) or general philosophy: the vital project of Ortega y Gasset, magnificently summarized by Marías (1941). Thus, among various affordable alternatives for the model-self, the person would opt for one of them all or would make it to his size. A recent study (Schick et al., 2020) has shown that an intrapersonal factor of intrinsic origin underlies self-esteem.

This model-self as a project would also be linked to the fulfillment of certain personal goals punctuated throughout life -study, work, consume-, revealing a temporal dimension in self-esteem. Consequently, this type of self-esteem would emerge when comparing the trajectory of achievements obtained by the subject with respect to a previously devised model trajectory of goals to achieve. In this longitudinal version we would therefore have self-esteem as proximity between two trajectories, compared to self-esteem as a coincidence between two self-profiles in the transversal version.

The model, as we have anticipated in the Introduction, does not assume any specific content or dimensionality of the self – our concepts of self-model and self-perceived, defined below, are used exclusively as terms of comparison. However, we admit, it will be convenient to expose, even very briefly, some considerations about the self, a complex construct with a long tradition in the literature. Obviously, space limitations prevent us from an exhaustive review of this concept, as it has been understood by the various theoretical approaches and, even less, from the existing empirical results on its dimensionality, differential functionality of the factors in various contexts, and even on the transcultural character of the self, and other related issues.

On the one hand, self-concept and self-esteem are concepts so closely related that they are almost indistinguishable and even used interchangeably (Pajares and Shuck, 2001; Shavelson and Bolus, 1982). On the other hand, there is also a broad debate about the dimensionality and hierarchical structure of the self - see (Baumeister et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2020; Marsh and O'Mara, 2008; Marsh and Shavelson, 1983; Rosenberg, 1979 ) to obtain a broad view on the matter. In this last regard, the theoretical structure of five factors - academic, social, emotional, family and physical - has been receiving empirical support, even in confirmatory factor analyzes in various countries with quite diverse cultures (Chen et al., 2020; García et al., 2013; García et al., 2018; Murgui et al., 2012; Tomas and Oliver, 2004). Obviously, a multidimensional approach to the self allows for more accurate predictions and a better explanation of certain mental disorders and specific behavioral problems (Chen et al., 2020; Fuentes et al., 2020; Gallarin et al., 2021; Garcia et al., 2021; al., 2018; Maiz and Balluerka, 2018).

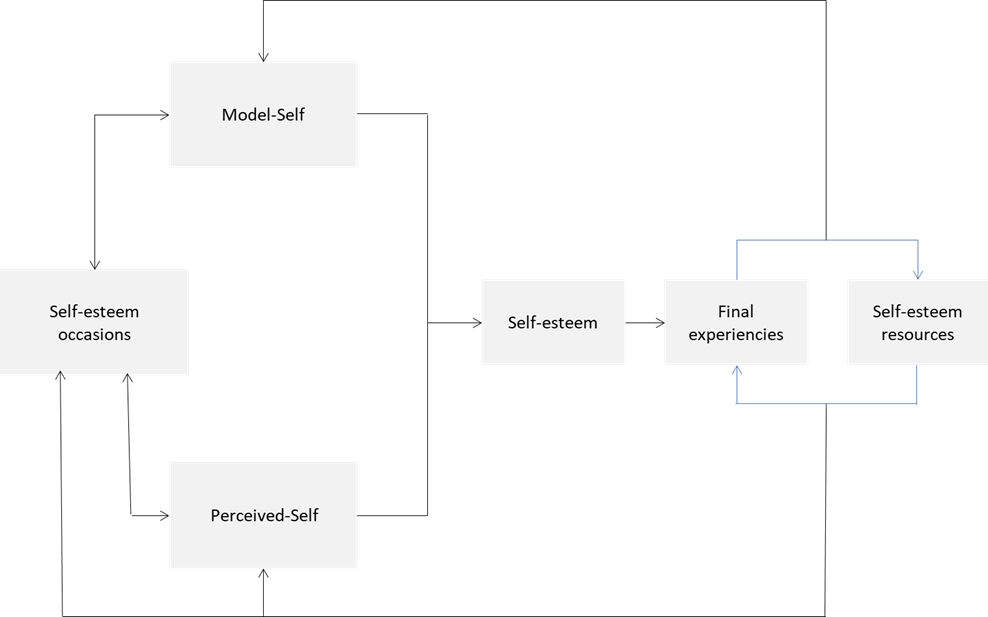

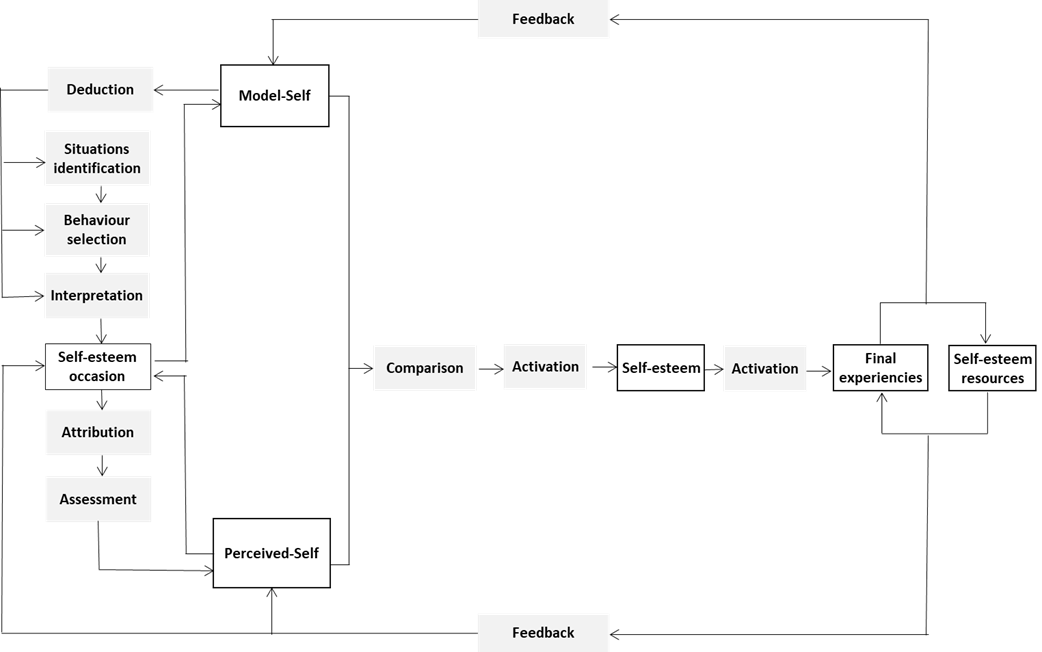

The model consists of two classes of elements: (a) components: situational antecedents, representations and consequent mental states, and (b) cognitive processes: process information between components (see Graphs 1 and 2). All of them are necessary moments in each cycle of self-esteem.

Graph 1: components of the self-esteem model

Occasions of self-esteem: those antecedent situations, or specific aspects or anticipated effects, where the person is, and that give rise to an assessment of the perceived-self with respect to the model-self. They cover a wide spectrum: social situations or current task execution, memory of past situations, anticipation of future situations... In the case of raising demands, the occasions for self-esteem already include how the subject has responded to them –Johnson (2010) ratifies a self-esteem based on performance.

When we define the concepts of model-self and perceived-self below, we refer solely and exclusively to them as moments or terms that intervene in the process of a comparison between two mental representations. As we have commented in the Introduction, its specific contents are assumed but not defined, they are the basic postulates in this work.

Model-self: mental scheme that works as an archetype to which the perceived-self is equated, and which is taken as a scale to assess the latter. By definition, it will be implicit to the person (Franck et al., 2008), but it could be explicit if it were the case of a personal project or become explicit during a therapy process. Its magnetism rests on an underlying belief in the person concerned that resembling this scheme will yield beneficial results; model-self not as an end in itself, but as an instrument: “if I am x, then I will get y.” Consequently, the model-self would be "loaded" with attitudes, behaviors..., considered adequate to obtain certain benefits: "if I am kind, generous..., then I will achieve social acceptance". Therefore, from this representation, expectations emerge about how to resolve the occasions of self-esteem. Johnson (2010) speaks of a self-esteem that one must earn through their achievements (earning).

Its content would be displayed as an ideal profile of qualities related to personal appearance, social competence or task execution..., and personal successes - academic, professional, social -, self-control, or self-respect in moral matters (Clucas, 2020). There are results that attest to this: self-esteem depends on those principles on which it is based (Pyszczynski et al., 2004); it meshes with basic motivations that drive the individual to achieve objectives and competencies (Maxwell and Bachkirova, 2010); plays a mediational role in academic self-efficacy (Bandura, 1986; Batool et al., 2017); personal competence is its best predictor (Soral and Kofta, 2020); and is linked to the desire for status (Anderson et al., 2015), the frustration of which leads to low self-esteem (von Soest et al., 2018). The features of its profile will be hierarchical, subordinated to each other according to their significance in absolute terms or relative to present situations.

Although a single model-self is presumed in the person's mind, two possibilities should not be ruled out: (i) that the individual can use different alternative self-models, using them as appropriate; and (ii) that due to social influence the current model-self is neutralized or even supplanted by another foreign model-self. But even if this were the case, this would not invalidate the functioning of the model since only one model-self and only one would intervene in each specific self-assessment.

Perceived-self: mental scheme of how the person perceives his own self at a given moment or period, constituting his self-concept. In Robson's (1989) questionnaire, situations or personal characteristics that lead to successive self-esteem are collected, such as being successful, self-control, pleasant personality, (not) looking horrible...

In connection with the longitudinal version of self-esteem, this scheme would incorporate "extensions of the self", an expression referring to the tangible and intangible results that the subject has obtained in various fields, and whose success or failure is attributed to himself. It is known how materialistic factors influence self-esteem (Gupta & Singh, 2019).

Self-esteem resources: representations stored in the memory of the person with information of any type: social, economic... - and which he could use instrumentally to correct the discrepancy suffered between his model-self and perceived-self. The richness of these resources will obviously depend on the training the individual has received, the knowledge acquired and the experience accumulated.

Self-esteem: mental state that includes the consideration and appreciation that one gives to oneself after having compared his two self-schemas, varying in tone according to the degree of coincidence between the two: the greater the coincidence, the higher the self-esteem or tone. Discrepancies with an ideal lead to low self-esteem (Renaud & McConnell, 2007); and the items to evaluate it reveal a tacit comparison: “I am capable of doing things as well as most other people” (Rosenberg, 1965).

Since self-esteem is subordinated to the person-environment interaction, it is convenient to introduce two complementary concepts here: (a) possible self-esteem: maximum feasible self-esteem given the current conditions of the person and their environment, which would be relative self-esteem; and (b) full self-esteem: self-esteem achieved when a perfect similarity occurs between the perceived-self and the model-self, which would be absolute self-esteem. The latter eventuality will constitute a singular event in the subject's life and will be stored with greater prominence in his episodic memory. In line with the aforementioned interaction, self-esteem will be updated, especially when it shows significant damage, and in order to restore the entire system: there are short-term effects of stress on self-esteem (Palmier-Claus et al., 2011); it itself suffers from fragility (Borton et al., 2012); and uncertainty about one's own self-esteem is linked to depression (Luxton and Wenzlaff, 2005).

Final experiences: states of consciousness that will harbor the consequences caused by self-esteem, being impregnated with the emotional tone corresponding to how the latter was. We say “final” because they close a complete cycle of updating self-esteem. They will oscillate from positive to negative in harmony with changes in current self-esteem, and will have a retroactive effect on self-schemas and self-esteem occasions.

To include the longitudinal version of self-esteem, the components of the model must be completed with these three new concepts: (a) Model-self of goals: scheme with those goals to be achieved over time, that the individual had set to estimate himself, (b) Perceived-self of achievements: outline with the trajectory of his successes and failures; and (c) Self-esteem due to achievements: that obtained after comparing the two previous schemes.

A set of serial cognitive processes connects the components of the model to each other. They require the assistance of cognitive and metacognitive resources for information processing, and are automatically triggered once the necessary background is given. They meet the criteria of cognitive process (Rowlands, 2010), and by their category they are subpersonal processes -output information only available for the subsequent process-, except when they precede the consequent mental states.

There are three nuclear processes that in turn give rise to derived processes, according to detail: (a) deduction and/or recovery of information from the model-self: generates expectations about how antecedent situations should be resolved, and leads to the subprocesses of identification of antecedent situations, selection and implementation of behaviors and interpretation of self-esteem occasions; (b) internal attribution: assigns personal responsibility for the outcome of the situation, and initiates the subprocess of valuing the perceived-self; and (c) comparison perceived-self-model-self: compares both schemes, assigning the corresponding self-esteem, and leads to the subprocesses of activation of the final experiences from the self-esteem, and feedback from the final experiences.

Graph 2: processes of the self-esteem model

Deduction and/or recovery: from a sufficiently rich and multiform model-self, these three blocks of information are deduced or recovered directly from its content: (a) class of situations, or pattern of characteristics, potentially relevant for self-esteem, (b) repertoire of appropriate behaviors to display or inhibit in these situations, and (c) set of rules of interpretation to judge whether or not the situation has been resolved favorably according to this scheme.

Identification of antecedent situations: process that takes as inputs: (a) antecedent situation: environmental or internal stimuli, and (b) pattern of situational characteristics relevant to self-esteem according to the model-self, considering whether or not there is adjustment. Its way out will consist of accepting or discarding the situation as an occasion for self-esteem. Some situations will raise performance demands on the subject, their compliance being a requirement for a positive assessment of the perceived-self - the same self-influences this process (Schäfer and Frings, 2019) and some disorders make it difficult (Cella et al., 2018).

Selection and implementation of behavior: process whose inputs are: (a) demands for action that could elevate the situation and (b) behaviors available to deal with it conveniently according to the model-self; selecting the behavior with the greatest probability of success, which will be exactly the one that simultaneously meets the situational demands and the expectations of success of the model-self. From representations and after identifying an element of a certain category, goals are generated as rules of action (Pylyshyn, 1984). Its output will be the implementation of the selected behavior, an event that will occur only when the individual has perceived the aforementioned demands. It is a crucial process for self-esteem that connects situational demands with a response chosen according to the model-self.

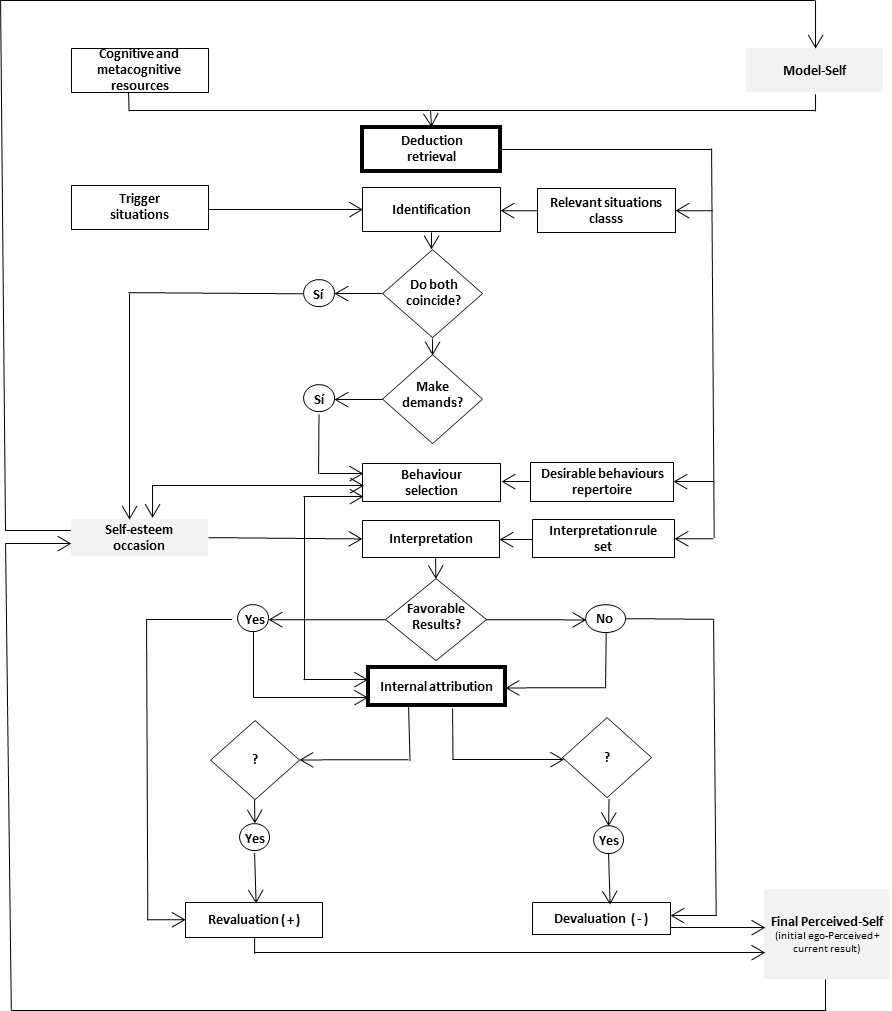

Interpreting self-esteem occasions: process with these inputs: (a) self-esteem occasion and (b) model-self criteria for judging its outcome; determining how it has been the same. Its output will be the valuation or devaluation of the perceived-self in line with the result produced. Although indirectly, here the two schemes of the self are connected for the first time.

Internal attribution: process that assigns the responsibility that the person attributes to himself for the result of the self-esteem occasion, being estimated or dismissed depending on whether it was success or failure. Its inputs are: (a) interpretation of the self-esteem occasion and (b) behavior implemented in the situation; its output being the concomitant valuation of the perceived-self. A negative attributional style together with low self-esteem is associated with depressive symptoms (Southall & Roberts, 2002). In successive cycles of self-esteem, feedback would take place between said inputs and output.

Appraisal of the perceived-self: process whose inputs are: (a) result of the self-esteem occasion itself, its passive appraisal, and (b) result according to the internal attribution made, its active appraisal. Both valuations will be added to each other in sign and value. We speak of "passive" or "active" assessment, referring to the null or direct participation of the subject in resolving the situation. Its output will be a final perceived-self, the sum of the initial perceived-self plus the value, with a negative or positive sign, corresponding to the result of the recent occasion for self-esteem.

Graph 3: Detailed assessment of the final perceived-self

Comparison model-self/perceived-self: process where (a) the model-self and (b) the final perceived-self enter, comparing each other; its output being the activation of a mental state where the concomitant self-esteem is collected. The two schemes of the self are directly connected here, both being evaluated on the same parameters.

Activation of self-esteem: it immediately follows the previous process and initiates this consequent mental state, being accessible to the consciousness of the interested party.

Activation of final experiences: process whose input and output are, respectively, the resulting self-esteem and the final consequences associated with it. This concludes a separate cycle of activation and maintenance of self-esteem, caused by each preceding situation. Certain environmental patterns activate automatic processes linked to self-esteem (Gawronski and Bodenhausen, 2006).

Feedback: process whose inputs are: (a) state of self-awareness of the final experiences, and (b) self-esteem resources that the subject has and can mobilize to improve his self-esteem; and its output will be the maintenance or modification of the inputs to the system, positive and negative feedback, respectively.

The proposed sequence of processes is consistent with the cognitive paradigm and its therapeutic applications for depression (Beck et al., 1979) or for intermittent explosive disorder (Gorenstein et al., 2007); based, furthermore, on matters of fact: the antecedent precedes its interpretation, and the results are prior to its attribution. It is foreseeable that the evaluation and monitoring of these processes will prove very useful in therapy with patients.

Since self-esteem is immersed in the person-environment dynamic, it is influenced by certain antecedent situations, among others, and especially, social relationships (Pyszczynski et al., 2004); and generates its particular consequences, being, therefore, an intermediate link in a more extensive causal chain. Next, we will examine how its updating and maintenance works, also pointing out the components of the model.

They represent a set of events of a given kind (Bunge, 1979) and include all those situational antecedents that trigger the self-esteem process. Depending on how they are resolved, it will serve to judge whether or not the perceived-self has satisfied the expectations of the model-self (see Graph 3). Three types of antecedents are considered: (a) occasions of external self-esteem: when the person is perceiving environmental information referring to himself or his actions: ““I receive signs of social rejection”, “I have gotten good grades”; (b) occasions of internal self-esteem: mental states or sensations of the person, memory or anticipation of results in past or future situations: “I am satisfied with what I did”, “I will not be able to behave appropriately”; and (c) complex self-esteem occasions: those where external and internal aspects are combined: “my boss congratulated me, and I really think I did well.” In cases of low self-esteem, the most frequent antecedents involve mistakes, failure or social rejection (Kolubinsky et al., 2016; McManus et al, 2009).

Although it may seem that there are spontaneous occasions of self-esteem, without any intervention from the subject, the model presupposes that a certain participation of the subject is involved in all of them, even if it had occurred a long time ago - remote participation - or was reduced to mere passive participation, simply physical presence: receiving a gesture of approval or rejection on the street. The subject's participation compromises the subsequent attribution of responsibility for the outcome of the situation, making the nature of his actions especially important. The latter faces a double difficulty: it must at the same time (a) satisfy the situational demands and (b) resolve the situation in accordance with the expectations of the model-self. Furthermore, the ever-changing condition of the person-environment interaction will continually raise new demands that will force the subject to give different responses to match their actions with the situational transformations that occur, under penalty of risking their self-esteem. Obviously, as the model-self becomes more demanding -obtaining not only social approval, but even gaining sociometric status (Anderson et al., 2015)-, it will be essential to mobilize more and more personal resources, and the risk of failing to meet such expectations will also be greater, since unsatisfied personal goals reduce self-esteem (Lindsay & Scott, 2005).

Two final observations: in self-esteem occasions: (a) an initial perceived-self is already given and influenced by the self-assessment resulting from the ongoing self-esteem occasion, updating it as a final perceived-self, and (b) due to social influence, the current model-self of the person may be inhibited, blocking the appropriate selection of behaviors and causing inappropriate action in the situation, thereby promoting a devaluation of the final perceived-self.

Although the model-self makes demands, it does not include in itself the way to fulfill them. It is postulated, however, that its content structure works as a principle to deduce, or perhaps directly recover, substantial information to efficiently execute the cognitive processes that operate on self-esteem. Specifically, this scheme would provide information to: (a) identify those antecedent situations that are occasions for self-esteem; (b) select and implement or inhibit behaviors on the occasion of current self-esteem; and (c) interpret the result achieved in each situation, according to certain rules. The interaction of the different occasions of self-esteem with the model-self will pulsate various parts of the scheme, promoting sequences of information transformation. Cognitive processes such as priming (Cowan, 2000) facilitate the activation of schemes from certain stimuli. Its effectiveness as a scheme is based on providing: (a) a set of clearly established pertinent situational patterns, (b) a wide and versatile repertoire of behaviors to implement in the various occasions that arise, and (c) consistent rules for interpreting results.

We will illustrate this functioning with a simple example: if “being a pleasant person” appeared in the model-self, then a situation preceding a social gathering would be identified as an occasion for self-esteem in the company of its demands, and an action that involved “conversing animatedly in the group” would be selected as an appropriate behavior option to receive the sympathies of the attendees and thus ensure self-esteem.

These experiences function as a term where a separate cycle of self-esteem is completed - antecedent plus sequence of processes -, consisting of states of consciousness that collect the ultimate consequences of self-esteem. Depending on this, they will be impregnated with an affective tone that will oscillate between a maximum positive, optimal experiences, and a maximum negative, terrible experiences; being in some cases truly intense experiences. Depending on their nature and intensity, they will lead to a retroactive process of maintenance or modification of the system components.

In the positive, they are experiences of self-satisfaction, self-confidence, self-acceptance and self-care (Jacob et al., 2010), and they will range from psychological well-being with feelings of joy or satisfaction to feelings of pride and self-complacency indicative of greater fulfillment or personal fulfillment: self-esteem predicts feelings of status and inclusion (Benson and Giacomin, 2020). In their phenomenal aspect, they will manifest to the individual as a feeling of carelessness for having reached a kind of goal -the perceived-self would become "transparent", in the positive sense given to this term by Metzinger (2009)- or of internal coherence between its cognitive, emotional and behavioral dimensions (Duro, 2005). They will free up cognitive resources or facilitate their access for other tasks or projects, since those people with positive beliefs about themselves become more involved in problem-solving processes (Roberts et al., 2020); cushioning the mental burdens of anxiety, high self-esteem (Pyszczynski et al., 2004).

At its negative pole, the person will experience self-distrust, self-rejection, self-criticism..., states colored by corresponding feelings - sadness, dejection, remorse -, which produce incapacity. Recurrent self-critical rumination in low self-esteem (Kolubinski et al., 2017, 2019; Sowislo and Orth, 2013) wastes the limited capacity of working memory (Cowan, 2000) in a sterile attempt to restore it – sadness causes episodes of ruminative questioning (Roberts et al., 2020). Low self-esteem also inhibits the subject's ability to perceive and act, keeping in mind that self-esteem mediates coping with situations (Kurtovic et al., 2018) - low self-esteem makes it difficult to perceive body signals (Cella et al., 2019). ), and it follows complications, such as resentment that negatively correlates with it (Murillo and Salazar, 2019) and mental disorders. It constitutes a vulnerability factor for depression (Franck et al., 2008; Steinberg et al., 2007), also in relation to types of self-esteem (Johnson, 2010), exacerbating personal defects and failures (Fennell, 2004), and even producing that disorder (Beck et al., 1979). At the same time, an excessive concern for social acceptance, very frequent in low self-esteem, leads to vigilance processes associated with anxiety (Beck et al., 1985), without forgetting that the variability of self-esteem, together with other factors, generates paranoid symptoms (Palmier-Claus et al., 2011).

A feedback loop will be activated by the final experiences to maintain or modify the inputs in subsequent self-esteem cycles. It will work in the short term for each occasion of current self-esteem, and in the medium and long term for more lasting maintenance. When the discrepancy between the self-schemas has exceeded a certain threshold, the concomitant negative experience will function as an incentive inciting the subject to reduce it, given that cognitive dissonance always enhances a corrective motivation (Festinger, 1957); although sometimes this correction is distorted: it would be the pathological rules of life (Fennell, 2004). Its retroactive effect will operate in two areas: (a) internal loop: circuit that interconnects the final experiences with the model-self and the perceived-self to make changes in these schemas, as a self-regulation mechanism; and (b) external loop: circuit that interconnects the final experiences with the perception and action on self-esteem occasions with a view to optimizing the latter, as an adaptive strategy. Obviously, the effectiveness of the feedback will depend on the amount of self-esteem resources that the person concerned can mobilize.

Occasions of self-esteem that contain an intentional social influence -advice, rejection- or casual -accidental exposure to more attractive models of self- will also act through the internal loop, changing pre-existing schemes temporarily or permanently. It must be distinguished feedback from influence: there a discrepancy is corrected and here the schemes are directly modified: someone imposes a model-self, a situation annuls the current model-self. Remember that both schemas of the self show permeability to influences from the internal environment -moods, proprioceptive sensations- and from the external environment -occasions of self-esteem.

To appease the discomfort of negative final experiences, the person will need to use all those self-esteem resources that are available to him: cognitive, metacognitive, social, economic... A reinterpretation of antecedent situations or reattribution of their result are examples of cognitive resources. It cannot be ruled out that access to these resources may be blocked by one's own dismissal, decision-making inhibited by lack of self-confidence.

In particular, they will be appropriate here for different reasons: (a) social skills such as showing empathy or providing social support: those with low self-esteem tend to ingratiate themselves more with third parties (Schmitte et al., 2019); (b) self-regulation capacities to adjust the self-esteem system, in line with the S-REF model (Wells & Matthews, 1994); (c) metacognitive resources -redirecting attention, monitoring background situations (Wells, 2009); and even, for some profiles of the model-self (d) economic resources or social influence to achieve certain professional positions, hire services or acquire assets: aesthetic interventions improve self-esteem (Richard et al., 2018).

The model with its analytical nature makes it possible to explain salient aspects of mental disorders and the functioning of existing therapies for low self-esteem. From its operating principles, it is postulated that the latter emerges from two basic differentials: (a) between the model-self and the perceived-self, and (b) between the resources available and necessary to recover self-esteem. In any case, the patient would be plunged into a means-ends conflict, in the origin and maintenance of which external factors - family environment, social influence - and internal factors - personal ambition, social deviation - will play a part.

Low self-esteem accompanies other mental disorders: eating disorders (Chang 2020), anxiety, behavioral and personality problems (Jacob et al., 2010; Pérez-Gramaje et al., 2019), certain psychoses (Hall and Tarrier, 2003); and, as a personal vulnerability factor (Butler et al., 1994; Franck et al., 2008; Sowislo and Orth, 2013; Steiger et al., 2015), it can provide a basis on which the pathological structure of other conditions is based: consistent self-esteem predicts the course of therapy for depression (Eberl et al., 2018), and its variability induces improvements in personality treatments (Cummings et al., 2012).

The model place its etiology on one or more of these defects: (a) vices in the configuration of self-schemas, (b) cognitive processes of self-esteem that are biased or inhibited for one reason or another: a variable self-esteem would lead to externalizing the result of events (Palmier-Claus et al., 2011), and (c) lack of effective negative feedback.

We will illustrate the above with some examples, separating them by components and processes: (a) components: a negative perceived-self would remain crystallized in the person's mind due to situations of abuse, harassment, family neglect... (McManus et al., 2009) or stigmatization, whose internalization damages self-esteem (Jahn et al., 2020), blocking its timely updating through successful actions, an essential therapeutic change (Ellis, 1996); an overestimation of the perceived-self would be equally harmful: vulnerable narcissism correlates negatively with self-esteem (Rohmann et al., 2019); (b) processes: biases when identifying antecedent situations, people with low self-esteem tend to make upward social comparisons (Parker et al., 2013); or misinterpretation of expectations, transforming legitimate aspirations into disturbing needs (Ellis & Grieger, 1986); conflict between the goals of self-regulation and adaptation, carried out, respectively, by the internal and external feedback loops: self-esteem mediates the conflict between family and work (Innstrand et al., 2010).

As we mentioned previously, there are numerous therapies in use for low self-esteem, some of which have recently been implemented, such as those derived from the metacognitive approach (Kolubinski et al., 2016, 2018, 2019), namely: individual cognitive-behavioral therapy with adults (Cummings et al. al., 2012; Hall and Tarrier, 2003; McManus et al., 2009; Pack and Condren, 2014; Parker et al., 2013; Waite et al., 2012; Whelan et al., , 2007), adolescents (Taylor and Montgomery, 2007) and children (Wanders et al., 2008), also in groups (Beattie and Beattie, 2018) and in coexistence with other disorders (Jacob et al., 2010; (Pack and Condren, 2014; Whelan et al. ., 2007); dialectical behavioral therapy (Roepke et al., 2011); rational-emotive therapy, even integrated with other therapies (Roghanchi et al., 2013); EMDR technique (Wanders et al., 2008); mindfulness approach (Fennell, 2004); coaching techniques (Maxwell and Bachkirova, 2010); or even fixed role therapy (Kelly, 1955), originally as a treatment for personality; there are also comparative studies between various therapies (Wanders et al., 2008).

The model can contribute to perfecting the application of these therapies, and lays the foundations for its own therapeutic project based on its structure and functioning: making the model-self explicit, improving the detection of occasions of self-esteem. In any case, it is maintained that self-esteem will be recovered solely and exclusively by optimizing the person-environment relationship in order to increase the chances of self-esteem that end in a good outcome.

Among the contributions of the proposed model, we would highlight its integrated nature - completing in a whole different concepts and results hitherto dispersed - and analytical, which allows explaining the updating and maintenance of self-esteem in real time; as well as its potential to develop future clinical applications in psychopathology and psychotherapy; its coherence with other psychological theories and constructs; and its origin in results in this field of research. Within its limitations, we understand that there is still a lack, among other things, of an adequate articulation of the transversal and longitudinal versions of self-esteem, and of elucidating how the automatic and deliberate aspects of the model-self are articulated.

In our opinion, future works should address: (a) the necessary formalization of the model and its empirical contrast; (b) a comprehensive and orderly exposition of a treatment program to adequately assess and adjust the various components and cognitive processes involved, as we have seen, in updating and maintaining self-esteem; as well as (b) a subsequent comparative analysis of its clinical efficiency with respect to other currently existing therapies.