AUCTORES

Globalize your Research

Research Article | DOI: https://doi.org/10.31579/2690-8808/145

Department of Pure and Applied Psychology, Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba-Akoko, Akungba-Akoko, Ondo State.

*Corresponding Author: Agesin, Bamikole Emmanue, Department of Pure and Applied Psychology, Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba-Akoko, Akungba-Akoko, Ondo State.

Citation: Agesin, Bamikole Emmanue. (2022 Perceived Prison Environment as Predictor of Prisoners’ Adjustment: The Mediating role of Resilience among Inmates in South-West Nigeria. Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Studies 3(10); DOI: 10.31579/2690-8808/145

Copyright: © 2022 Agesin, Bamikole Emmanue, This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received: 06 October 2022 | Accepted: 25 October 2022 | Published: 26 November 2022

Keywords: perceived prison environment; prison adjustment; resilience; inmates

The concept of studying prison behaviour, particularly adjustment after incarceration has evolved with the cause of time and has ultimately become a veritable source for understanding how prisoners employ personal adjustment characteristics in their respective socio-cultural, economic and demographic circumstances. These behaviours actually define social position of inmates and provide a better understanding of behavioural process that reduces the overall economic cost of adjusting problems within prison communities. The problem of adjustment is under-reported in common place within the Nigerian correctional Service. This study examined the role of prison environment as predictor of Prisoners’ adjustment among inmates: The mediatory role of resilience.Using a correlational survey design and systematic sampling technique, four hundred and seventy-six convicts responded to Prison Environment scale, resilience Scale, and Prison Adjustment Scale. Analysis of the data with Linear and multiple regression and Sobel statistics. Findings revealed that, Prison environment significantly predicted prisoners’ adjustment β.26, t 5.25’’, p< .01, Resilience significantly predicted prisoners’ adjustment β.18, t 2.25’, p< .05 Furthermore, the strength with which resilience mediated the relationship between prison environment and prison adjustment was significant. Thus, (Ƶ = 2.31, p., <. 05). It was recommended that, government may need to take into consideration the condition of the prison environment and resilience when designing programs toward promoting or enhancing psychologically well-adjusted prison inmate.

There has been great concern about how inmates adjust to prison life, the patterns of adaptation to imprisonment can have significant implications (Humber, Webb, Piper, Appleby & Shaw, 2013). The extent to which adaptations are predisposed by the prison environment itself and or influenced by the prisoners’ characteristics has been a matter of significant consideration (Africa Centre for the Prevention of Crime, 2010).

The discomforts of confinement affect prisoners in diverse ways (Jeff, Levin & Amit, 2010). Jimoh (2007), asserts that prisoners are exposed to a new culture of deprivation, solitude and alienation play a significant role in prisoner’s adjustment pattern. The combined impact of solitude, the emotional imbalance of prison life, and the separation from loved ones often lead to depression among incarcerated individuals (Ashkar & Kenny, 2008).

These and many more circumstances pervading prison environment may lead to a myriad of behavioural concerns in the lives of these individuals and those of significant other within this category of people (Humber, et al., 2013). The increase in the number of cases self-mutilation in prison communities has agitated research interest and global concern (Africa Centre for the Prevention of Crime, 2010). Therefore, it becomes important that understanding behavioural mechanisms that underlie prisoner adjustment in prison populations calls for research attention.

Adjustment generally refers to utilization of skills and experiences that facilitate personal integration into the society to which one belongs (Weiten, Dunn, & Hammer, 2011). Similarly, adjustment also refers to the psychological processes through which people manage or cope with the demands or challenges of everyday life (Weiten et al., 2011).

Bakare (1990) opined that adjustment connotes behaviours that enable a person to get along and be comfortable in his particular social settings; hence, such behaviour as nervousness, depression or withdrawing from the society is a question of adjustment. Adjustment can also be seen as the manner in which a person meets his environment, or seen as the way a person feels and behaves under new life situations and experiences (Jeff, Levin & Amit, 2010).

Therefore, prisoners’ adjustment refers to the processes through which inmates manage and cope with the demands of the prison environment and its experiences. The extent to which an inmate’s adjustment to imprisonment is influenced by the prison environment itself (indigenous) or influenced by the prisoner’s ‘pre prison characteristics’ (imported) has long been of considerable debate (Dhami, Ayton, & Loewenstein, 2007).

It is necessary to see prisoners’ adjustment as unique survival achievements towards the goal of maintaining one’s mind, spirit, and body in prison. The human experience of incarceration is intentionally hidden from society (Haney, 2001). In the present study, one of the possible predictors of Prisoners adjustment is Prison Environment.

Prison Environment

Perceived prison environment refers to the social, emotional, organizational and physical characteristics of a correctional institution as perceived by inmates and staff (Toch, 1977). It is often used synonymously with the term “prison climate”. The environment inmates are confined in consists of two distinct entities: structural and individual. The individual entities are not necessarily physical objects found in the prison environment. Rather, these structural entities are made up of eight environmental dimensions that address: personal freedom, inmate activities, support, structure, social relations, and emotional feedback for the inmate from the prison staff, and inmate privacy and safety (Toch, 1977). These eight dimensions are seen as making up the primary environmental concerns of the inmate that are shared among the prison population.

The Nigerian prison environment with regard to amenities have been described as dehumanizing (Soyinka, 1972), and in spite of the public outcry by human rights organisations, most prison yards in Nigeria are overcrowded beyond capacity (Jimoh, 2007). Prisoners often face life threatening challenges and environmental situations such as overcrowding; having to be forcefully placed in the same cell with hardened criminals, being prevented from seeing loved ones which inevitably may lead to poor prisoner’s adjustment that may result to self-harm tendencies (Jeff et al., 2010).

Currently, Nigeria prisons are housing 49,000 in two hundred and thirty four prisons out of which 20% are convicts while the rest are awaiting trial inmates (Amnesty International Report, 2012 cited in, Awopetu, 2014).. According to some studies outside Nigeria (Young, Palta, Dempsey, Skatrud, Weber, Badr, 1993; Wicklow & Espie, 2000) report that 20-30% of the United State prison population between the ages of 30-60 has scored relatively high on psychological distress measurements. The pain of imprisonment carries certain psychological cost. Whenever, one is imprisoned, he is likely to suffer certain deprivation; separation due to incarceration which can be a stressful experience and leads to poor level of prison adjustment. Studies on incarceration in Nigeria have been directed at the prevalence of violence in prison (Okunola, Aderinto, & Atere, 2002). From the review of literatures, it seems most study done on incarceration have focused on the prevalence of imprisonment in Nigeria. There is dearth of study and empirical data on the connection between prison environment, and mediatory role of resilience on prison adjustment among prison inmates in Nigeria. Therefore, the present study attempts to address this knowledge in gap. The study is modest in that it attempts to determine the predicting roles of prison environment and the mediatory role of resilience in predicting prisoners’ adjustment in some selected prisons in western Nigeria. It is my hope that, this study moves towards a better understanding of the challenges this problematic behavior presents to mental health.

Resilience

Another variable of interest in this study that may predict prisoners’ adjustment is how resilient the prisoners are. Resilience is one of the psychological resources that could help prisoner cope with the challenges in the prison environment. Despite the vast body of research on resilience, there is little agreement on a single definition of resilience among scholars. In fact, it has been variously defined (Carle & Chassin, 2004). Resilience could be describe as a reference framework to describe the positive aspects and mechanisms in an individual, group, material, or system which, when facing a destabilizing and disruptive situation affecting their integrity and stability, enables them to hold up, cope, recover, and come out strengthened by it (Vaquero, Urrea, & Mundet, 2014). In short, resilience is best defined as the ability of a system to absorb disturbances and still retain its basic function and structure (Armstrong, Galligan & Critchley, 2011) and as the capacity to change in order to maintain the same identity (Arslan, 2016). Resilience is when, “Some individuals have a relatively good outcome despite having experienced serious stresses or adversities – their outcome being better than that of other individuals who suffered the same experiences” (Rutter, 2013).

Relatively assuming, a few researchers have showed that resilience has been found to play an essential part in decreasing depressive symptoms (Southwick & Charney, 2012) and trauma symptoms (Fan & Olatunji, 2013). Resilience exists in people who develop psychological and behavioural capacities that allow them to remain calm during crises and to move on from the incident without long-term negative consequences (Olatunji, Armstrong, Fan & Zhao, 2014).

Resilience have been significantly linked to health promoting and wellbeing, especially when faced with adversity (Ong, et al., 2006). However, not all individuals who experience unpleasant events in childhood will become troubled adolescence. People who demonstrate stable and healthy functioning levels and are able to adapt positively to the resilient individuals (Fan & Olatunji, 2013).

Resilience is commonly explained and studied in context of a two-dimensional construct concerning the exposure of adversity and the positive adjustment outcomes of that adversity (Luther & Cicchetti, 2000). These two judgments, one is about a positive adaptation which is considered behavioural or social competence or success at meeting any particular task at a specific life stage, and the other about the significance of risk associated with negative life conditions that are related to adjustment difficulties. Therefore, the present study attempts to fill this lacuna by examining perceived prison environment as a predictor of prisoners’ adjustment among prison inmates in South-West Nigeria: The mediating role of resilience.

Statement of Hypotheses

Research Design and Participants

The study adopted correlational survey design. The researcher is interested in knowing the predictive effect of the dependent variable (prison environment) on prison adjustment (dependent variables) and the Mediatory role of Resilience.

The population of study comprised representative of all prisoners from the six prison facilities in the south west part of Nigeria. They are as follows, Akure Medium Prison Olokuta Akure, Ondo State, Ilesha Prison, Osun State, Abeokuta Prison, Ogun State, Agodi prison, Ibadan, Oyo State, Kirikiri Maximum prison, Apapa Lagos State, and Ado-Ekiti Prison, Ekiti State.

Measures

Four major instruments were used to collect data from the respondents. They include;

Biographic Information Questionnaire: This contain the personal details of participants such as gender, age, religion, academic qualification, marital status, length of sentence.

Prison Environment Inventory: This is made up of self-reported 48- items developed by Wright (1985). It has eight (8) sections namely, activities (1-6), emotional feedback (7-13), freedom (14-19), privacy (20-25), safety (26-31), social (32-37), structure (38-42) and support (43-48). The PEI-48 is a 4- item Likert format scale ranging from (that 0 = Never, 1 = Seldom, 2 = Often, and 3 = Always.) and some of the sample items include (1) There is at least one movie each week, (2) An inmate obtains training if he wants (3) Inmates have something to do every night. (4) The guards tell inmates when they do well. (5) The guards ask inmates about their personal feelings. The pilot study shows Cronbach alpha (α) = 83, but Cronbach (α) =.83 was reported for the present study. Composite scores above the mean score means supportive Prison While scores below the mean indicate Non-supportive prison.

Prisoner’s Adjustment Scale (PAQ): This is a 20 item self-report instrument PAQ developed by (Wrights, 1985). The PAQ assesses perceptions such as prisoners’ comfort around inmates, comfort with staff, feelings of anger, frequency of illness, trouble sleeping, fears of being attacked, physical fights, heated arguments with inmates etc. Participants responded by indicating their level of agreement to each item based on five-point scale, ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Examples of the items include, I have discomfort around fellow inmates, have discomfort around staff, understand rules, have necessary training etc. The score above mean score indicate positive/ better prison adjustment, while score below mean score indicate poor level of prison adjustment. Wright reported a Cronbach alpha of (α) =0.93 and the Guttman Split half reliability (r) =0.89.The pilot study shows Cronbach alpha (α) =67, but Cronbach (α)-.69 was reported for the present study. PAQ was interpreted in terms of the sum of the total aggregate score of the items. Scores above the mean indicate increased adjustment and scores lower than the mean indicate less adjustment.

Resilience scale:

Resilience was assessed using a resilience scale (RS-25) developed by Wagnild & Young (1993) to provide clinicians and researchers a shorter instrument to reduce participant burden. The RS-14 is a 7- item Likert format scale ranging from (1- strongly disagrees to 7- strongly Agree) and some of the sample question include (1.) I usually manage one way or another. (2) I fell proud that I have accomplished things in life (5.) I feel that I can handle many things at a time. Wagnild and Young (1993) reported reliability co-efficient of .91 the original RS. A Cronbach Alpha of (α) = .78 was reported for the present study. The scores above the mean indicate resilient Prisoners, while scores below indicate non resilient Prisoners.

Procedure

Six prison formations were randomly selected from the south western zone in Nigeria based on balloting. The choice of even numbers was arrived at via the ballot technique. That is odd and even were wrapped differently and all put together in a box. Individual prisoners were asked to pick one and he or she picked a wrapped paper upon which even numbers were written. Prisons facilities labeled even numbers on the list were selected. Approval was earlier obtained from the department of Psychology, Ekiti State University; that introduced me to the Prison facilities for the research purpose, with this approval; I was able to visit different prisons that were selected in the study. With permission and approval obtained from the respective prison authorities, the researcher used systematic sampling technique (i.e. odd and even numbers) on the list of prison inmates provided by each prison officials of the selected prisons to choose participants among the inmates that were involved in the research work.

Eighty (80) prisoners were randomly selected through simple balloting from each of the chosen prison. Hence, four hundred and eighty (480) prisoners were used for the study. However, two (2) questionnaires were not adequately completed, hence the reason for not including them in the processing of the result. Finally, four hundred and sixty-eight (478) questionnaires were adequately completed and returned questionnaire were used for the processing of the result of this study. Male=249 (52.1), Female =229(47.9), Christianity 397(83.1) Islam 81(16.9), Age mean=23.55, SD=3.49, N=478 Gender= mean=1.52, SD=500, N=478, Sentence Period mean=9.44, SD=12.68, N=460, Religion mean=1.17, SD=376, N=478, Prison Environment mean=60.61, SD=16.557, N=478, Religiosity mean=69.04, SD=18.094, N=478, Resilience mean=79.09, SD=13.254, N=478, Prisoner’s Adjustment mean=43.89, SD=9.667, N=478, Self-Harm Urges mean=33.29, SD=12.767, N=478.

The three instruments were packaged together as a questionnaire with 3 sections where section A seeks demographic information, Section B while section C, centers on Self-Harm and section F focus on prison Adjustment scale. These were administered to the participants by the researcher after necessary permissions have been sought which will give the researcher access into the yards. The instruments were collected immediately after completion. The exercise lasted for the period of six weeks with a week allocated for each prison. However, only one day in the week was used for each prison but no one could predict the very day permission would be granted to interact with the prisoners in the yards, possibly for security reasons.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics was used to analyze the socio-demographic variables. The study hypotheses were tested using multiple regression analysis and t-test analysis.

Test of Relationship among the Study Variables

Pearson Product Moment correlation (PPMC) was used to inter-correlate the study variables in order to ascertain the extent and direction of relationships among them. The result is presented below.

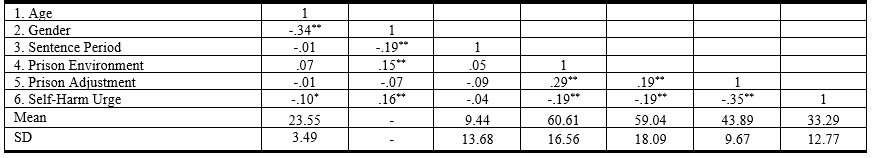

Table 1: Correlation Matrix Showing the Mean, SD and the Relationship among the Study Variables

Perceived religious af..= Perceived religious affiliation **. Note: * p<.01, * <. 0.5, N 478. Gender was coded male 0 female 1.

The result in table 1.1 shows that Prisoners environment significantly correlated with Inmates’ adjustment [r = (476) =.29**p <.01], such that, when the prison environment is supportive the prisoner is better adjusted vice

Hypothesis 1

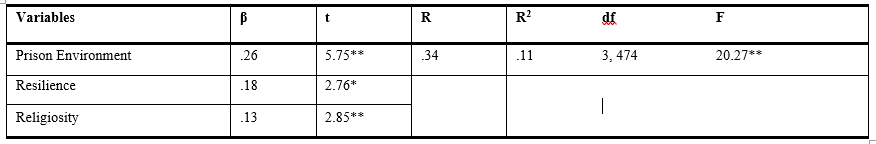

Table 2 Showing Prison Environment, Resilience Predicting Prisoners’ Adjustment

** p< 0 N=478>Prison environment significantly predicted prisoners’ adjustment β.26, t 5.25’’, p< .01, such that, the more conducive and supportive the prison environment is, the more adjusted the prisoners are to the prison environment. Resilience significantly predicted prisoners’ adjustment β.18, t 2.25’, p< .05 such that, the resilient prisoners are better adjusted to the prison environment, than those who are not resilient

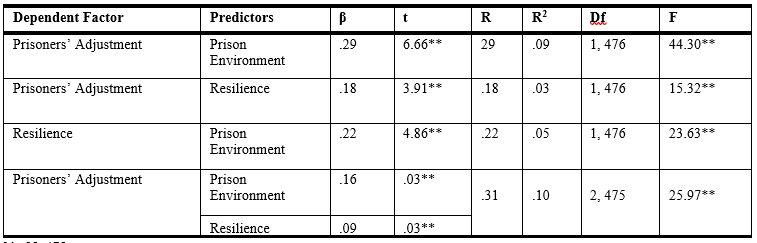

Table 3 Showing Resilience mediating the relationship between Prison Environment and Prisoners’ Adjustment

Prison environment significantly predicted prisoners’ adjustment (β .29, t 6.66, p< .01).Resilience significantly predicted prisoners’ adjustment (β .18,t 3.91, p< .01).Prison environment significantly predicted Resilience (β .22, t= 4.86, p< .01).Prison environment significantly predicted prisoners’ adjustment (β .16, t= 03, p< .01).

When Resilience was introduced, the β reduce to .β .16, when resilience is .09. From the result of the analysis, it is therefore clear that there is partial mediation of resilience in the predictive influence of prison environment on the prisoners’ adjustment in the study.

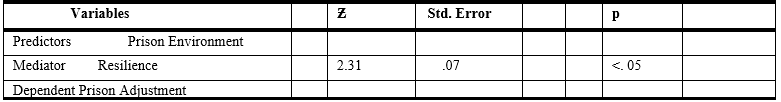

Table 4: Sobel Summary Showing the Strength of Mediation between Prison Environment and Prison Adjustment by Resilience

The result of the Sobel test indicated that strength with which resilience mediated the relationship between prison environment and prison adjustment was significant. Thus, (Ƶ = 2.31, p., <. 05

It is evident that there is a relationship between the result of this present study and previous ones. The result of hypothesis one which stated that, prison environment, will significantly predict prisoners’ adjustment was accepted. This finding is consistent with the work of Parcel et al., (2000) and Denman et al, (2002), on impact environment has on the social adjustment mostly on Schools, Universities (Dooris, 2001; Whitehead, 2004) and hospitals (Pelikan, et al, 2001; Whitehead, 2004) as well as other organizations. Petersilia, (2003) asserts that the social deprivation of the jail custodial environment and its experience can have lasting effects the mental well-being of prisoners. The discordant conditions of the jail environment play a significant role in the social and professional development of the imprisoned and in the development of behavior that is adopted by the prisoners who eventually exhibit this behaviour when reabsorbed into the society leading to adjustment problems.

The result demonstrate that external cues and contingency factors such as environment and resilience play significant roles in the prisoners adjustment, and one reason for this may be that conducive and supportive prison environment provides optimism towards life and significant others. For example, Tompkins, et al., (2007) who found that choosing to take illicit substance was frequently influenced by other prisoners; for example, being in prison at the same time with drug-using friends or sharing a cell with a drug-user could increase people’s inclination to engage in drug taking. Also, MacKenzie & Goodstein, 1986; McEwen, 1978; Osgood(1985) corroborates that if some leniency is given towards a regiment of choice and control, inmates can experience reduced level of stress, as well as abuse, injury, discomfort, and other negative byproducts of the prison environment. Invariably, though, not all inmates could be afforded leniency due to their disposition such as those in maximum protection prisons.

Similarly, empirical data such as, Swann and James, (1998) and Stark et al., (2006) support the fact that, social and environmental characteristics of the prison setting usually show degenerating effect on prisoners’ health. To help hold this assertion, Petersilia, (2003) examined the role of socialization within a custodial environment through the lens of the prison inmate. These author reported that analysis of the development of inmate behavior has been the socialization process that actually begins with incarceration in the jail system, and this alters in varying degrees, behavioural and physiological changes in prisoners.

From this finding, it’s obvious that prison has been implicated to have effect on prisoners’ adjustment and self-harm urge just as it was implicated to exacerbate, rather than lessen, individuals’ inclinations to use illicit drugs just as reported by (Lynch & Sabol,2004).Stover & Weilandt (2007) and Cope (2003) highlighted the associations of prison environment and drug use, these authors emphasized that prisoner’s often use drugs to counteract boredom or to “slip away” from the realities of prison life, in other words, drug intake is been used to pass time. In the same vein, Cope (2003) demonstrated how young offenders often manipulated their perception of time in prison through using different types of psychoactive substances. Smoking cannabis, for example, could make “time fly” in prison, although, cocaine was often avoided because of the brevity associated with its euphoria.

The result of this study also validate the second hypothesis that resilience will play a mediatory role between prison environment and prisoners adjustment. The finding indicates that, resilience showed a significant correlation with prisoners’ adjustment. Despite the growing report that prison inmates show signs of depression and melancholy, when ecological factors seem unsupportive, contemporary recent findings suggest otherwise, for instance, Wagnild (2003) who examined the role of morale, life satisfaction, and resilience reported a significant relationship, when correlated with prisoner adjustment in Pretoria, South Africa. However, variety of factors may be responsible, for this which include but not limited to, modern facilities and procedures, the role of technology, prison budgeting and noticeable increase in humanitarian activities scheduled for prisoners. Criminologists (Petersilia, 2003) have documented that over time ex-offenders become ‘embedded’ in criminality, and they gradually weaken their bonds to conventional society. After years of engaging in a criminal lifestyle, reestablishing these bonds with mainstream society becomes very difficult. Re-establishing societal bonds is a crucial aspect of all successful ex-offender re-integration.

The result of this finding is consistent with the results of Hardy, Wagnild & Young, (1990) and Concato, & Gill, (2004) who reportedly found inverse relationships between depression and resilience. Moreover, the finding corroborates the result of Nygren, Alex, Jonsen, Gustafson, Norberg& Lundman, (2005), who reported that mental health was correlated with resilience in women, but not men. Matsen, Best & Garmezy (1990) explained that three outstanding properties of resilient individuals are; the capacity to develop and progress despite of adverse and risky conditions and occurrence of positive consequences after experiencing them, the permanent capability to perform under stress and tension, and ability to return trauma caused by experiencing adverse situations in life. The result of this finding also, substantiates the work of Pattillo, Weiman & Western, (2004) who reported that resilient individuals participate more in health promoting behaviors, welcome involvement in daily activities, enjoy challenges, and prefer change to stability. The term resiliency generally refers to processes and factors that halt the growth path from risk of problem-causing behaviors and psychological damage and bring about adaptive consequences despite of adverse conditions (Mohammadi, 2005). Also the findings supported the works of Schaefer and Moos's model in (Schaefer & Moos, 1992), where it was reported that resiliency is the strongest predictor of posttraumatic growth related to childhood parentification; resilience explained 14% of the variance in PTG (Hooper, Marrota, & Lanthier, 2008).

Hypothesis two which state that, resilience will significantly mediate the relationship among prisoners’ adjustment, prison environment was confirmed. The findings support the study by Ong, Bergeman, Bisconti & Wallace, (2006) who found that, resilience mediated the association between stress and negative mood, such that individuals who were more resilient showed less mood reactivity to and faster mood recovery from daily stressors. Also the result of this study is convergent with the findings of Moein & Ladan, (2015), which suggested that cognitive emotion self-regulation mediated by resiliency is able to directly or indirectly predict impulsivity and that the relationship between cognitive emotion self-regulation and impulsivity is not a simple linear relationship as other variables such as resiliency play an important mediating role (at least for positive strategies) in this regard.

The result established the assertion that resilience is considered a personality characteristic that mediates the negative effects of stress and promotes adaptation (Wagnild & Young, 1993). In addition to having particular personality characteristics, resilient individuals often rely on protective factors to help adjust to difficult times. According to the Resiliency model (Richardson, 2002) individuals experience disruption to their lives when a stressor is encountered, they rely on internal protective factors, such as self-reliance and good health, as well as external protective factors, such as social networks, to restore balance in their lives. Likewise, the result is in support of the findings of Meng, Xiao-Xi, YuGe & Lie (2015) which reported that resilience partially mediated in the relationship between stress and life satisfaction among Chinese medical students. Ong, Bergeman, Bisconti & Wallace, (2006) report that individuals who were more resilient showed less mood reactivity to and faster mood recovery from daily stressors. Equally, Akbari & Khormaiee (2015) reported that resilience predicted healthy psychological state which played partial mediating role between emotional intelligence and psychological well-being among students.

First, self-reported survey approach was used in the generation of data. This method was chosen to accelerate the collection of a large amount of quantifiable data, and to protect the anonymity of the inmates. While survey data is acceptable in studies of this kind, it is recommended that future research utilize a mixed methods approach using both quantitative and qualitative techniques and independent sources to verify the survey data.

Another shortcoming of this study is that of responder bias, which is common to all survey studies due to respondents’ belief of projecting a good image rather than be seen in different perspective. Similar to other research studies, this project is not without its own inadequacy. For instance, the sample size used for this research work may not guarantee generalization on this subject matter, to be true representatives of the entire number prison inmates we have in Nigeria prison facilities and by implication, the result of this work should be generalize with caution.

It is imperative to state here that, only prison facilities from the South-West were randomly selected, and this only represent a fraction of the entire prison facilities in the country. Owing to the relative simplicity of this analysis there is always the possibility of omitting relevant variables. However, despite these limitations, this study represents one of the largest population-based studies of self-harm among this category of people.

In trying to understand the plights of inmates with focus on the prison environment, it is important to be cognizant of the varying circumstances that exist within prisons environment. These circumstances characterized by what Toch (1977) identified as part of prison environment dimensions (structure, privacy, support, activities, emotional support, freedom, social relations, and safety) such give rise to unpredictable environmental dimensions. These dimensions, and their comprising factors, make it difficult for prison facilities to address the ideal of rehabilitation yet alone those of deterrence, incapacitation, and retribution while trying to address and/or placate inmate concerns.

Additionally, the function of the prison and its impact on both inmate and guard contributes greatly to problems associated with these dimensions. The difficulties encountered with inmate concerns is heightened by the demands of society which argues for the barest of housing conditions, little or no recreational activities, and for stiffer, longer sentences while asking that those who are released be rehabilitated in hopes of reducing recidivism.

To potentially better the prison ideal of rehabilitation and reduce inmate concerns, effort and resources should be tailored to individual inmates rather than the total inmate population. This can start when offenders enter the prison by using sensitive psychological battery testing to help identify inmates who require specialized needs and placing them into the correct program.

These programs would contain the proper resources needed to specifically deal and address unique inmate problems. Inmates who receive specific treatment regimen may feel as if the criminal justice system views them as an individual rather than a number, and by so doing enhance their level of adjustment to the prison environment.

The findings of this present study have proved relevant to the Nigerian prison situation the theoretical positions of (Goleman 1998; Goltfredson 1998; Zohar & Marshall 2000; Zohar & Berman 2001; Akinboye, Akinboye & Adeyemo. 2002; Adeyemo 2007, 2008; & Jimoh 2007). On the basis of the above, the following recommendations were made;

The government may need to take into consideration the significant roles of prison environment, personality trait of prison inmates (resilience) when designing program toward promoting or providing a prison environment for psychologically well-adjusted prison inmate. While there is no magic bullet, if there was a simple and easy solution no doubt it would have been implemented years ago, some radical changes are needed if it will aid adjustment to the prison environment. There needs to be an inherent shift in the philosophy of prison in this country, and so the researcher recommends that the Ministry of interior in collaboration with that of ministry of Justice publishes a new statement on the purposes of prison, where the primary purpose is rehabilitation, reformation and reintegration which acknowledges that all persons deprived of their liberty shall be treated with respect for their human rights.. In addition to using the prison environment scale across countries, attention should be given to studying the effects of the prison environment on cultural relativity, social class and ethnicity, comparing the results to determine how inmates from different cultures are affected by prison environment. Finally, a performance indicator is to be developed to help local authorities gauge and evaluate the success of inmate resilience and emotional wellbeing. Meanwhile, further studies on adjustment is required, especially if psychological factors such as personality types, emotional regulation, and emotional intelligence is considered.

Clearly Auctoresonline and particularly Psychology and Mental Health Care Journal is dedicated to improving health care services for individuals and populations. The editorial boards' ability to efficiently recognize and share the global importance of health literacy with a variety of stakeholders. Auctoresonline publishing platform can be used to facilitate of optimal client-based services and should be added to health care professionals' repertoire of evidence-based health care resources.

Journal of Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Intervention The submission and review process was adequate. However I think that the publication total value should have been enlightened in early fases. Thank you for all.

Journal of Women Health Care and Issues By the present mail, I want to say thank to you and tour colleagues for facilitating my published article. Specially thank you for the peer review process, support from the editorial office. I appreciate positively the quality of your journal.

Journal of Clinical Research and Reports I would be very delighted to submit my testimonial regarding the reviewer board and the editorial office. The reviewer board were accurate and helpful regarding any modifications for my manuscript. And the editorial office were very helpful and supportive in contacting and monitoring with any update and offering help. It was my pleasure to contribute with your promising Journal and I am looking forward for more collaboration.

We would like to thank the Journal of Thoracic Disease and Cardiothoracic Surgery because of the services they provided us for our articles. The peer-review process was done in a very excellent time manner, and the opinions of the reviewers helped us to improve our manuscript further. The editorial office had an outstanding correspondence with us and guided us in many ways. During a hard time of the pandemic that is affecting every one of us tremendously, the editorial office helped us make everything easier for publishing scientific work. Hope for a more scientific relationship with your Journal.

The peer-review process which consisted high quality queries on the paper. I did answer six reviewers’ questions and comments before the paper was accepted. The support from the editorial office is excellent.

Journal of Neuroscience and Neurological Surgery. I had the experience of publishing a research article recently. The whole process was simple from submission to publication. The reviewers made specific and valuable recommendations and corrections that improved the quality of my publication. I strongly recommend this Journal.

Dr. Katarzyna Byczkowska My testimonial covering: "The peer review process is quick and effective. The support from the editorial office is very professional and friendly. Quality of the Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions is scientific and publishes ground-breaking research on cardiology that is useful for other professionals in the field.

Thank you most sincerely, with regard to the support you have given in relation to the reviewing process and the processing of my article entitled "Large Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of The Prostate Gland: A Review and Update" for publication in your esteemed Journal, Journal of Cancer Research and Cellular Therapeutics". The editorial team has been very supportive.

Testimony of Journal of Clinical Otorhinolaryngology: work with your Reviews has been a educational and constructive experience. The editorial office were very helpful and supportive. It was a pleasure to contribute to your Journal.

Dr. Bernard Terkimbi Utoo, I am happy to publish my scientific work in Journal of Women Health Care and Issues (JWHCI). The manuscript submission was seamless and peer review process was top notch. I was amazed that 4 reviewers worked on the manuscript which made it a highly technical, standard and excellent quality paper. I appreciate the format and consideration for the APC as well as the speed of publication. It is my pleasure to continue with this scientific relationship with the esteem JWHCI.

This is an acknowledgment for peer reviewers, editorial board of Journal of Clinical Research and Reports. They show a lot of consideration for us as publishers for our research article “Evaluation of the different factors associated with side effects of COVID-19 vaccination on medical students, Mutah university, Al-Karak, Jordan”, in a very professional and easy way. This journal is one of outstanding medical journal.

Dear Hao Jiang, to Journal of Nutrition and Food Processing We greatly appreciate the efficient, professional and rapid processing of our paper by your team. If there is anything else we should do, please do not hesitate to let us know. On behalf of my co-authors, we would like to express our great appreciation to editor and reviewers.

As an author who has recently published in the journal "Brain and Neurological Disorders". I am delighted to provide a testimonial on the peer review process, editorial office support, and the overall quality of the journal. The peer review process at Brain and Neurological Disorders is rigorous and meticulous, ensuring that only high-quality, evidence-based research is published. The reviewers are experts in their fields, and their comments and suggestions were constructive and helped improve the quality of my manuscript. The review process was timely and efficient, with clear communication from the editorial office at each stage. The support from the editorial office was exceptional throughout the entire process. The editorial staff was responsive, professional, and always willing to help. They provided valuable guidance on formatting, structure, and ethical considerations, making the submission process seamless. Moreover, they kept me informed about the status of my manuscript and provided timely updates, which made the process less stressful. The journal Brain and Neurological Disorders is of the highest quality, with a strong focus on publishing cutting-edge research in the field of neurology. The articles published in this journal are well-researched, rigorously peer-reviewed, and written by experts in the field. The journal maintains high standards, ensuring that readers are provided with the most up-to-date and reliable information on brain and neurological disorders. In conclusion, I had a wonderful experience publishing in Brain and Neurological Disorders. The peer review process was thorough, the editorial office provided exceptional support, and the journal's quality is second to none. I would highly recommend this journal to any researcher working in the field of neurology and brain disorders.

Dear Agrippa Hilda, Journal of Neuroscience and Neurological Surgery, Editorial Coordinator, I trust this message finds you well. I want to extend my appreciation for considering my article for publication in your esteemed journal. I am pleased to provide a testimonial regarding the peer review process and the support received from your editorial office. The peer review process for my paper was carried out in a highly professional and thorough manner. The feedback and comments provided by the authors were constructive and very useful in improving the quality of the manuscript. This rigorous assessment process undoubtedly contributes to the high standards maintained by your journal.

International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews. I strongly recommend to consider submitting your work to this high-quality journal. The support and availability of the Editorial staff is outstanding and the review process was both efficient and rigorous.

Thank you very much for publishing my Research Article titled “Comparing Treatment Outcome Of Allergic Rhinitis Patients After Using Fluticasone Nasal Spray And Nasal Douching" in the Journal of Clinical Otorhinolaryngology. As Medical Professionals we are immensely benefited from study of various informative Articles and Papers published in this high quality Journal. I look forward to enriching my knowledge by regular study of the Journal and contribute my future work in the field of ENT through the Journal for use by the medical fraternity. The support from the Editorial office was excellent and very prompt. I also welcome the comments received from the readers of my Research Article.

Dear Erica Kelsey, Editorial Coordinator of Cancer Research and Cellular Therapeutics Our team is very satisfied with the processing of our paper by your journal. That was fast, efficient, rigorous, but without unnecessary complications. We appreciated the very short time between the submission of the paper and its publication on line on your site.

I am very glad to say that the peer review process is very successful and fast and support from the Editorial Office. Therefore, I would like to continue our scientific relationship for a long time. And I especially thank you for your kindly attention towards my article. Have a good day!

"We recently published an article entitled “Influence of beta-Cyclodextrins upon the Degradation of Carbofuran Derivatives under Alkaline Conditions" in the Journal of “Pesticides and Biofertilizers” to show that the cyclodextrins protect the carbamates increasing their half-life time in the presence of basic conditions This will be very helpful to understand carbofuran behaviour in the analytical, agro-environmental and food areas. We greatly appreciated the interaction with the editor and the editorial team; we were particularly well accompanied during the course of the revision process, since all various steps towards publication were short and without delay".

I would like to express my gratitude towards you process of article review and submission. I found this to be very fair and expedient. Your follow up has been excellent. I have many publications in national and international journal and your process has been one of the best so far. Keep up the great work.

We are grateful for this opportunity to provide a glowing recommendation to the Journal of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy. We found that the editorial team were very supportive, helpful, kept us abreast of timelines and over all very professional in nature. The peer review process was rigorous, efficient and constructive that really enhanced our article submission. The experience with this journal remains one of our best ever and we look forward to providing future submissions in the near future.

I am very pleased to serve as EBM of the journal, I hope many years of my experience in stem cells can help the journal from one way or another. As we know, stem cells hold great potential for regenerative medicine, which are mostly used to promote the repair response of diseased, dysfunctional or injured tissue using stem cells or their derivatives. I think Stem Cell Research and Therapeutics International is a great platform to publish and share the understanding towards the biology and translational or clinical application of stem cells.

I would like to give my testimony in the support I have got by the peer review process and to support the editorial office where they were of asset to support young author like me to be encouraged to publish their work in your respected journal and globalize and share knowledge across the globe. I really give my great gratitude to your journal and the peer review including the editorial office.

I am delighted to publish our manuscript entitled "A Perspective on Cocaine Induced Stroke - Its Mechanisms and Management" in the Journal of Neuroscience and Neurological Surgery. The peer review process, support from the editorial office, and quality of the journal are excellent. The manuscripts published are of high quality and of excellent scientific value. I recommend this journal very much to colleagues.

Dr.Tania Muñoz, My experience as researcher and author of a review article in The Journal Clinical Cardiology and Interventions has been very enriching and stimulating. The editorial team is excellent, performs its work with absolute responsibility and delivery. They are proactive, dynamic and receptive to all proposals. Supporting at all times the vast universe of authors who choose them as an option for publication. The team of review specialists, members of the editorial board, are brilliant professionals, with remarkable performance in medical research and scientific methodology. Together they form a frontline team that consolidates the JCCI as a magnificent option for the publication and review of high-level medical articles and broad collective interest. I am honored to be able to share my review article and open to receive all your comments.

“The peer review process of JPMHC is quick and effective. Authors are benefited by good and professional reviewers with huge experience in the field of psychology and mental health. The support from the editorial office is very professional. People to contact to are friendly and happy to help and assist any query authors might have. Quality of the Journal is scientific and publishes ground-breaking research on mental health that is useful for other professionals in the field”.

Dear editorial department: On behalf of our team, I hereby certify the reliability and superiority of the International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews in the peer review process, editorial support, and journal quality. Firstly, the peer review process of the International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews is rigorous, fair, transparent, fast, and of high quality. The editorial department invites experts from relevant fields as anonymous reviewers to review all submitted manuscripts. These experts have rich academic backgrounds and experience, and can accurately evaluate the academic quality, originality, and suitability of manuscripts. The editorial department is committed to ensuring the rigor of the peer review process, while also making every effort to ensure a fast review cycle to meet the needs of authors and the academic community. Secondly, the editorial team of the International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews is composed of a group of senior scholars and professionals with rich experience and professional knowledge in related fields. The editorial department is committed to assisting authors in improving their manuscripts, ensuring their academic accuracy, clarity, and completeness. Editors actively collaborate with authors, providing useful suggestions and feedback to promote the improvement and development of the manuscript. We believe that the support of the editorial department is one of the key factors in ensuring the quality of the journal. Finally, the International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews is renowned for its high- quality articles and strict academic standards. The editorial department is committed to publishing innovative and academically valuable research results to promote the development and progress of related fields. The International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews is reasonably priced and ensures excellent service and quality ratio, allowing authors to obtain high-level academic publishing opportunities in an affordable manner. I hereby solemnly declare that the International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews has a high level of credibility and superiority in terms of peer review process, editorial support, reasonable fees, and journal quality. Sincerely, Rui Tao.

Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions I testity the covering of the peer review process, support from the editorial office, and quality of the journal.

Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions, we deeply appreciate the interest shown in our work and its publication. It has been a true pleasure to collaborate with you. The peer review process, as well as the support provided by the editorial office, have been exceptional, and the quality of the journal is very high, which was a determining factor in our decision to publish with you.

The peer reviewers process is quick and effective, the supports from editorial office is excellent, the quality of journal is high. I would like to collabroate with Internatioanl journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews journal clinically in the future time.

Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions, I would like to express my sincerest gratitude for the trust placed in our team for the publication in your journal. It has been a true pleasure to collaborate with you on this project. I am pleased to inform you that both the peer review process and the attention from the editorial coordination have been excellent. Your team has worked with dedication and professionalism to ensure that your publication meets the highest standards of quality. We are confident that this collaboration will result in mutual success, and we are eager to see the fruits of this shared effort.

Dear Dr. Jessica Magne, Editorial Coordinator 0f Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions, I hope this message finds you well. I want to express my utmost gratitude for your excellent work and for the dedication and speed in the publication process of my article titled "Navigating Innovation: Qualitative Insights on Using Technology for Health Education in Acute Coronary Syndrome Patients." I am very satisfied with the peer review process, the support from the editorial office, and the quality of the journal. I hope we can maintain our scientific relationship in the long term.

Dear Monica Gissare, - Editorial Coordinator of Nutrition and Food Processing. ¨My testimony with you is truly professional, with a positive response regarding the follow-up of the article and its review, you took into account my qualities and the importance of the topic¨.

Dear Dr. Jessica Magne, Editorial Coordinator 0f Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions, The review process for the article “The Handling of Anti-aggregants and Anticoagulants in the Oncologic Heart Patient Submitted to Surgery” was extremely rigorous and detailed. From the initial submission to the final acceptance, the editorial team at the “Journal of Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions” demonstrated a high level of professionalism and dedication. The reviewers provided constructive and detailed feedback, which was essential for improving the quality of our work. Communication was always clear and efficient, ensuring that all our questions were promptly addressed. The quality of the “Journal of Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions” is undeniable. It is a peer-reviewed, open-access publication dedicated exclusively to disseminating high-quality research in the field of clinical cardiology and cardiovascular interventions. The journal's impact factor is currently under evaluation, and it is indexed in reputable databases, which further reinforces its credibility and relevance in the scientific field. I highly recommend this journal to researchers looking for a reputable platform to publish their studies.

Dear Editorial Coordinator of the Journal of Nutrition and Food Processing! "I would like to thank the Journal of Nutrition and Food Processing for including and publishing my article. The peer review process was very quick, movement and precise. The Editorial Board has done an extremely conscientious job with much help, valuable comments and advices. I find the journal very valuable from a professional point of view, thank you very much for allowing me to be part of it and I would like to participate in the future!”

Dealing with The Journal of Neurology and Neurological Surgery was very smooth and comprehensive. The office staff took time to address my needs and the response from editors and the office was prompt and fair. I certainly hope to publish with this journal again.Their professionalism is apparent and more than satisfactory. Susan Weiner

My Testimonial Covering as fellowing: Lin-Show Chin. The peer reviewers process is quick and effective, the supports from editorial office is excellent, the quality of journal is high. I would like to collabroate with Internatioanl journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews.

My experience publishing in Psychology and Mental Health Care was exceptional. The peer review process was rigorous and constructive, with reviewers providing valuable insights that helped enhance the quality of our work. The editorial team was highly supportive and responsive, making the submission process smooth and efficient. The journal's commitment to high standards and academic rigor makes it a respected platform for quality research. I am grateful for the opportunity to publish in such a reputable journal.

My experience publishing in International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews was exceptional. I Come forth to Provide a Testimonial Covering the Peer Review Process and the editorial office for the Professional and Impartial Evaluation of the Manuscript.

I would like to offer my testimony in the support. I have received through the peer review process and support the editorial office where they are to support young authors like me, encourage them to publish their work in your esteemed journals, and globalize and share knowledge globally. I really appreciate your journal, peer review, and editorial office.

Dear Agrippa Hilda- Editorial Coordinator of Journal of Neuroscience and Neurological Surgery, "The peer review process was very quick and of high quality, which can also be seen in the articles in the journal. The collaboration with the editorial office was very good."

I would like to express my sincere gratitude for the support and efficiency provided by the editorial office throughout the publication process of my article, “Delayed Vulvar Metastases from Rectal Carcinoma: A Case Report.” I greatly appreciate the assistance and guidance I received from your team, which made the entire process smooth and efficient. The peer review process was thorough and constructive, contributing to the overall quality of the final article. I am very grateful for the high level of professionalism and commitment shown by the editorial staff, and I look forward to maintaining a long-term collaboration with the International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews.

To Dear Erin Aust, I would like to express my heartfelt appreciation for the opportunity to have my work published in this esteemed journal. The entire publication process was smooth and well-organized, and I am extremely satisfied with the final result. The Editorial Team demonstrated the utmost professionalism, providing prompt and insightful feedback throughout the review process. Their clear communication and constructive suggestions were invaluable in enhancing my manuscript, and their meticulous attention to detail and dedication to quality are truly commendable. Additionally, the support from the Editorial Office was exceptional. From the initial submission to the final publication, I was guided through every step of the process with great care and professionalism. The team's responsiveness and assistance made the entire experience both easy and stress-free. I am also deeply impressed by the quality and reputation of the journal. It is an honor to have my research featured in such a respected publication, and I am confident that it will make a meaningful contribution to the field.

"I am grateful for the opportunity of contributing to [International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews] and for the rigorous review process that enhances the quality of research published in your esteemed journal. I sincerely appreciate the time and effort of your team who have dedicatedly helped me in improvising changes and modifying my manuscript. The insightful comments and constructive feedback provided have been invaluable in refining and strengthening my work".

I thank the ‘Journal of Clinical Research and Reports’ for accepting this article for publication. This is a rigorously peer reviewed journal which is on all major global scientific data bases. I note the review process was prompt, thorough and professionally critical. It gave us an insight into a number of important scientific/statistical issues. The review prompted us to review the relevant literature again and look at the limitations of the study. The peer reviewers were open, clear in the instructions and the editorial team was very prompt in their communication. This journal certainly publishes quality research articles. I would recommend the journal for any future publications.

Dear Jessica Magne, with gratitude for the joint work. Fast process of receiving and processing the submitted scientific materials in “Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions”. High level of competence of the editors with clear and correct recommendations and ideas for enriching the article.

We found the peer review process quick and positive in its input. The support from the editorial officer has been very agile, always with the intention of improving the article and taking into account our subsequent corrections.

My article, titled 'No Way Out of the Smartphone Epidemic Without Considering the Insights of Brain Research,' has been republished in the International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews. The review process was seamless and professional, with the editors being both friendly and supportive. I am deeply grateful for their efforts.

To Dear Erin Aust – Editorial Coordinator of Journal of General Medicine and Clinical Practice! I declare that I am absolutely satisfied with your work carried out with great competence in following the manuscript during the various stages from its receipt, during the revision process to the final acceptance for publication. Thank Prof. Elvira Farina

Dear Jessica, and the super professional team of the ‘Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions’ I am sincerely grateful to the coordinated work of the journal team for the no problem with the submission of my manuscript: “Cardiometabolic Disorders in A Pregnant Woman with Severe Preeclampsia on the Background of Morbid Obesity (Case Report).” The review process by 5 experts was fast, and the comments were professional, which made it more specific and academic, and the process of publication and presentation of the article was excellent. I recommend that my colleagues publish articles in this journal, and I am interested in further scientific cooperation. Sincerely and best wishes, Dr. Oleg Golyanovskiy.

Dear Ashley Rosa, Editorial Coordinator of the journal - Psychology and Mental Health Care. " The process of obtaining publication of my article in the Psychology and Mental Health Journal was positive in all areas. The peer review process resulted in a number of valuable comments, the editorial process was collaborative and timely, and the quality of this journal has been quickly noticed, resulting in alternative journals contacting me to publish with them." Warm regards, Susan Anne Smith, PhD. Australian Breastfeeding Association.

Dear Jessica Magne, Editorial Coordinator, Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions, Auctores Publishing LLC. I appreciate the journal (JCCI) editorial office support, the entire team leads were always ready to help, not only on technical front but also on thorough process. Also, I should thank dear reviewers’ attention to detail and creative approach to teach me and bring new insights by their comments. Surely, more discussions and introduction of other hemodynamic devices would provide better prevention and management of shock states. Your efforts and dedication in presenting educational materials in this journal are commendable. Best wishes from, Farahnaz Fallahian.

Dear Maria Emerson, Editorial Coordinator, International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews, Auctores Publishing LLC. I am delighted to have published our manuscript, "Acute Colonic Pseudo-Obstruction (ACPO): A rare but serious complication following caesarean section." I want to thank the editorial team, especially Maria Emerson, for their prompt review of the manuscript, quick responses to queries, and overall support. Yours sincerely Dr. Victor Olagundoye.

Dear Ashley Rosa, Editorial Coordinator, International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews. Many thanks for publishing this manuscript after I lost confidence the editors were most helpful, more than other journals Best wishes from, Susan Anne Smith, PhD. Australian Breastfeeding Association.

Dear Agrippa Hilda, Editorial Coordinator, Journal of Neuroscience and Neurological Surgery. The entire process including article submission, review, revision, and publication was extremely easy. The journal editor was prompt and helpful, and the reviewers contributed to the quality of the paper. Thank you so much! Eric Nussbaum, MD

Dr Hala Al Shaikh This is to acknowledge that the peer review process for the article ’ A Novel Gnrh1 Gene Mutation in Four Omani Male Siblings, Presentation and Management ’ sent to the International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews was quick and smooth. The editorial office was prompt with easy communication.

Dear Erin Aust, Editorial Coordinator, Journal of General Medicine and Clinical Practice. We are pleased to share our experience with the “Journal of General Medicine and Clinical Practice”, following the successful publication of our article. The peer review process was thorough and constructive, helping to improve the clarity and quality of the manuscript. We are especially thankful to Ms. Erin Aust, the Editorial Coordinator, for her prompt communication and continuous support throughout the process. Her professionalism ensured a smooth and efficient publication experience. The journal upholds high editorial standards, and we highly recommend it to fellow researchers seeking a credible platform for their work. Best wishes By, Dr. Rakhi Mishra.

Dear Jessica Magne, Editorial Coordinator, Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions, Auctores Publishing LLC. The peer review process of the journal of Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions was excellent and fast, as was the support of the editorial office and the quality of the journal. Kind regards Walter F. Riesen Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. Walter F. Riesen.

Dear Ashley Rosa, Editorial Coordinator, International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews, Auctores Publishing LLC. Thank you for publishing our article, Exploring Clozapine's Efficacy in Managing Aggression: A Multiple Single-Case Study in Forensic Psychiatry in the international journal of clinical case reports and reviews. We found the peer review process very professional and efficient. The comments were constructive, and the whole process was efficient. On behalf of the co-authors, I would like to thank you for publishing this article. With regards, Dr. Jelle R. Lettinga.

Dear Clarissa Eric, Editorial Coordinator, Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Studies, I would like to express my deep admiration for the exceptional professionalism demonstrated by your journal. I am thoroughly impressed by the speed of the editorial process, the substantive and insightful reviews, and the meticulous preparation of the manuscript for publication. Additionally, I greatly appreciate the courteous and immediate responses from your editorial office to all my inquiries. Best Regards, Dariusz Ziora

Dear Chrystine Mejia, Editorial Coordinator, Journal of Neurodegeneration and Neurorehabilitation, Auctores Publishing LLC, We would like to thank the editorial team for the smooth and high-quality communication leading up to the publication of our article in the Journal of Neurodegeneration and Neurorehabilitation. The reviewers have extensive knowledge in the field, and their relevant questions helped to add value to our publication. Kind regards, Dr. Ravi Shrivastava.

Dear Clarissa Eric, Editorial Coordinator, Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Studies, Auctores Publishing LLC, USA Office: +1-(302)-520-2644. I would like to express my sincere appreciation for the efficient and professional handling of my case report by the ‘Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Studies’. The peer review process was not only fast but also highly constructive—the reviewers’ comments were clear, relevant, and greatly helped me improve the quality and clarity of my manuscript. I also received excellent support from the editorial office throughout the process. Communication was smooth and timely, and I felt well guided at every stage, from submission to publication. The overall quality and rigor of the journal are truly commendable. I am pleased to have published my work with Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Studies, and I look forward to future opportunities for collaboration. Sincerely, Aline Tollet, UCLouvain.

Dear Ms. Mayra Duenas, Editorial Coordinator, International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews. “The International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews represented the “ideal house” to share with the research community a first experience with the use of the Simeox device for speech rehabilitation. High scientific reputation and attractive website communication were first determinants for the selection of this Journal, and the following submission process exceeded expectations: fast but highly professional peer review, great support by the editorial office, elegant graphic layout. Exactly what a dynamic research team - also composed by allied professionals - needs!" From, Chiara Beccaluva, PT - Italy.

Dear Maria Emerson, Editorial Coordinator, we have deeply appreciated the professionalism demonstrated by the International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews. The reviewers have extensive knowledge of our field and have been very efficient and fast in supporting the process. I am really looking forward to further collaboration. Thanks. Best regards, Dr. Claudio Ligresti