AUCTORES

Globalize your Research

Research Article | DOI: https://doi.org/10.31579/2578-8949/115

1 College of Dentistry, The Ohio State University, Ohio, United States of America.

2 Department of Mathematical Sciences, University of Bath, Bath, United Kingdom.

3 Department of Orthodontics, UNC Adams School of Dentistry, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

4 Department of Public Administration, School of Public and International Affairs, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, North Carolina.

5 Department of Orthodontics, UNC Adams School of Dentistry, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

6 Department of Developmental Biology, Harvard School of Dental Medicine.

7 Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, UNC Adams School of Dentistry, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

8 Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Wake Forest Baptist Health, Wake Forest, North Carolina.

9 Department of Plastic & Oral Surgery, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

10 Department of Otolaryngology/Head and Neck Surgery, University of North Carolina Health, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

11 Department of Plastic & Oral Surgery Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

12 Department of Plastic Surgery, Wake Forest Baptist Health, Wake Forest, North Carolina.

13 Department of Otolaryngology, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts.

14 Department of Plastic Surgery, University of North Carolina Health, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

*Corresponding Author: Carroll Ann Trotman, College of Dentistry, The Ohio State University, Ohio, United States of America.

Citation: Carroll Ann Trotman, Julian Faraway, M. Elizabeth Bennett, G. David Garson, Ceib Phillips, et al., (2023), Decision Considerations and Strategies for Lip Surgery in Patients with Cleft lip/Palate: A Qualitative Study, Dermatology and Dermatitis, 8(5); DOI:10.31579/2578-8949/115

Copyright: © 2023, Carroll Ann Trotman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of The Creative Commons. Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Received: 03 July 2023 | Accepted: 31 July 2023 | Published: 27 October 2023

Keywords: cleft lip/palate; decision-making; clinical trial; lip repair; lip revision; qualitative

Objective: To qualitatively assess surgeons’ decision making for lip surgery in patients with cleft lip/palate (CL/P).

Design: Prospective, non-randomized, clinical trial.

Setting: Clinical data institutional laboratory setting.

Patients, Participants: The study included both patient and surgeon participants recruited from four craniofacial centers. The patient participants were babies with a CL/P requiring primary lip repair surgery (n=16) and adolescents with repaired CL/P who may require secondary lip revision surgery (n=32). The surgeon participants (n=8) were experienced in cleft care. Facial imaging data that included 2D images, 3D images, videos, and objective 3D visual modelling of facial movements were collected from each patient, and compiled as a collage termed the ‘Standardized Assessment for Facial Surgery (SAFS)’ for systematic viewing by the surgeons.

Interventions: The SAFS served as the intervention. Each surgeon viewed the SAFS for six distinct patients (two babies and four adolescents) and provided a list of surgical problems and goals. Then an in-depth-interview (IDI) was conducted with each surgeon to explore their decision-making processes. IDIs were conducted either ‘in person’ or virtually, recorded, and then transcribed for qualitative statistical analyses using the Grounded Theory Method.

Results: Rich narratives/themes emerged that included timing of the surgery; risks/limitations and benefits of surgery; patient/family goals; planning for muscle repair and scarring; multiplicity of surgeries and their impact; and availability of resources. In general, there was surgeon agreement for the diagnoses/treatments.

Conclusions: The themes provided important information to populate a checklist of considerations to serve as a guide for clinicians.

Little information exists on surgeons’ decision-making process for primary lip repair and lip revision surgery in patients with Cleft Lip/Palate (CL/P). These surgical decisions affect the esthetic and functional outcomes of the nasolabial region and the outcomes on the soft tissue form and function/movement is highly variable (Trotman et al., 2013). More often than not, soft tissue disabilities persist after the primary lip repair in the form of facial disfigurements and impaired circumoral movements that require additional revision surgeries (Tanikawa et al., 2010; Trotman et al., 2010). The burden of care for patients and their caregivers is great and includes [1] Direct costs (e.g., treatment expenses, time lost at work) and indirect costs (e.g., health/emotional well-being of the child and caregivers) (Boulet et al., 2009). [2] Reports that the quality of parent-infant interactions is adversely affected and children develop psychological problems (Hunt et al., 2007), and that many wish to have additional surgery later in life (Marcusson, 2001). [3] Complaints of anxiety and awkward moments by patients during social interactions (Hebl et al., 2000). (4) Evidence of socioeconomical problems in the form of diminished income and educational accomplishments for patients compared with their non-cleft counterparts (Ramstad et al., 1995; Trost et al., 2007).

The decision to perform a lip revision relies mainly on a subjective assessment of the patient’s face by the surgeon in conjunction with the desires of the patient/caregivers. Soft tissue movement has been given less consideration mainly because of challenges to assess and improve movement (e.g., the amount/quality of the tissue available). Even when attempts are made to assess movement, there are no quantitative or visual aids to incorporate movement into the treatment planning. To that end, our research group has developed a systematic assessment approach, the Standardized Assessment for Facial Surgery or SAFS, that can be used to quantify facial disability (Faraway & Trotman, 2011; Trotman et al., 2007; 2013). It incorporates a collage of three-dimensional (3D) facial quantitative dynamic and static measures and visual dynamic comparisons of patients soft tissue movements versus controls for an objective assessment, as well as two-dimensional (2D), 3D, and video facial images for a subjective assessment. The approach allows surgeons to broaden their "vista" of a patient’s problems and potentially make decisions on a patient specific basis (Trotman et al., 2010; 2013). During the treatment planning process, surgeons are required to mentally integrate multiple sources of information/data (Crebbin et al., 2013; Flin et al., 2007) along a continuum ranging from intuitive and subconscious (using the SAFS subjective data) to analytical and conscious (using the SAFS objective data). Decisions are reached by a combination of each according to the complexity of the situation and the surgeon’s level of experience. These types of ‘expert decisions’ are a relatively unexplored area in the surgical sciences.

Thus, the primary objective of this study was to assess how surgeons integrate the SAFS objective measures and visual aids with the SAFS systematic subjective assessment in decision-making for lip surgery in patients with CL/P. This study tests the null hypothesis that when surgeons are presented with individual patients’ SAFS data, no common themes emerge from their decisions for the surgical management of children with repaired CL/P who may benefit from revision surgery and infants with unrepaired CL/P requiring initial lip repair. A secondary area explored was the extent to which surgeons agreed on their recommendations for surgery and the diagnosis and treatment plan.

This research was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health NIDCR branch (Grant # U01 DE024503). This qualitative study was part of a non-randomized clinical trial (NCT03537976). The participants were recruited from six Craniofacial Centers: The University of North Carolina (UNC) and Wake Forest Baptist Health Craniofacial Centers in Chapel Hill and Winston Salem, North Carolina; and Boston Children’s Hospital, Massachusetts General Hospital, Shriners Hospitals for Children, and Tufts Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts. Tufts University School of Dental Medicine (TUSDM) Boston, Massachusetts served as the data coordinating center. The study protocol (see supporting information), consent, and HIPAA documents were approved by the Tufts Health Sciences and UNC Biomedical Human Subjects Institutional Review Boards.

At each Center, the patient’s surgeon made the initial clinical decision to perform surgery, and subsequently, the patient was screened to determine eligibility. Patients were enrolled in two groups. Group 1 (age range 4 to 21 years) comprised two sub-groups: Patients who were recommended for, and could benefit from, a lip revision (n=22, termed revision), and patients who were not recommended for revision (n=10, termed non-revision). The non-revision sub-group served as a negative control for the revision. Group 2 (age range birth to 8 months) were infants scheduled for primary lip repair (n=16, termed repair). Table 1 gives the eligibility criteria for the participants.

| Participants | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

| Revision & Non-Revision | • For the revision patients, presence of a previously repaired unilateral or bilateral cleft lip and palate with a complete cleft of the primary palate and at least a partial or complete cleft of the secondary palate. • For the revision patients, a professional clinical recommendation by the craniofacial plastic / oral maxillofacial surgeon for a full or partial thickness lip revision. • For the revision and non-revision patients, patient (depending on age) and guardian have ability to comprehend verbal instructions in English, Spanish, or Chinese. • For the revision and non-revision patients, patient (depending on age) or guardian able to give consent / assent and have an ability to provide a signed and dated informed consent form in English, Spanish, or Chinese. • For the revision and non-revision patients, patient (depending on age) or guardian willing to comply with all study procedures and be available for up to 2 study visits. • For the revision and non-revision patients, patient age 4 to 21 years. | • Lip revision surgery within the past year. • A diagnosis of a craniofacial anomaly other than cleft lip (and palate). • A medical history of collagen vascular disease, or systemic neurologic impairment. • Mental, visual, or hearing impairment to the extent that comprehension or ability to perform tests associated with the collection of the imaging data is hampered. |

| Repair | • Patient has presence of an unrepaired unilateral or bilateral cleft lip and palate with a complete cleft of the primary palate and at least a partial or complete cleft of the secondary palate. • Parent/guardian is willing and able to provide a signed and dated informed consent form in English, Spanish, and Chinese. • Parent/guardian is willing and able to comprehend verbal instructions in English, Spanish, or Chinese. • Parent/guardian is willing and able to comply with all study procedures and be available for the duration of the study visits. • Patient age birth to 8 months. | • A diagnosis of a craniofacial anomaly other than cleft lip (and palate). • A medical diagnosis of collagen vascular disease, and systemic neurologic impairment. • Mental, visual, or hearing impairment to the extent that the infant’s ability to perform tests associated with the collection of the imaging data is hampered. |

| Surgeon | • Surgeons experienced in the care and treatment of patients with CL/P. • Surgeons should belong to a Cleft lip and palate team as defined by the ACPA Team standards document (www.acpa-cpf.org/team_care/). • Surgeon should have a minimum of 2 lip revision and 2 lip repair surgeries per 12-month period. • The total number of surgeons represents a broad range of experience specific to the length of time the surgeon has been treating patients with cleft lip and palate and the length of service on a cleft lip and palate team. Ideally, the length of time specific to surgical experience will include the following two categories: Surgeon-raters with < 5> • Surgeons’ willingness to participate and availability for the duration of the study. | • Surgeons who have previously used the 3D facial images and the dynamic facial movement data of the SAFS protocol prior to their enrollment in this study. |

Table 1: Revision and non-revision patients, lip repair infants, and surgeon eligibility criteria.

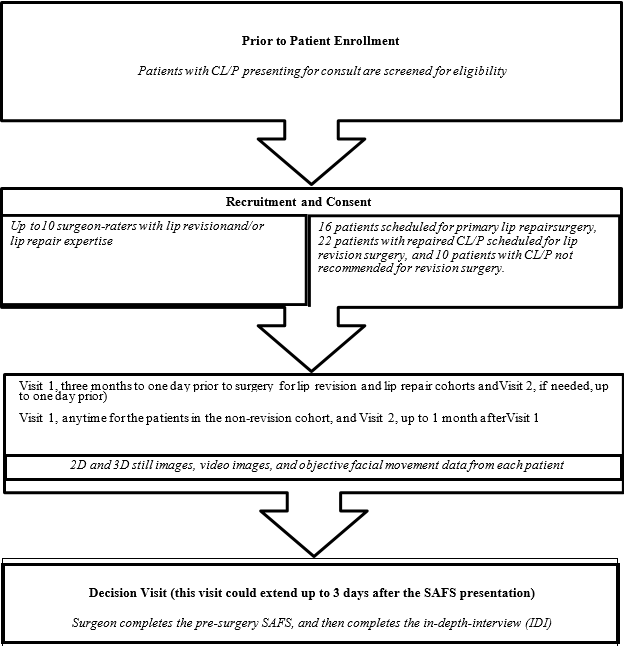

The patients attended Facial Animation Laboratories located at TUSDM and UNC for data collection visit(s). For the revision and repair patients, a first visit occurred at no greater than three months and up to one day before the scheduled surgery, and if needed a second visit occurred to complete data collection up to one day before surgery. For the non-revision patients, the first visit occurred at any time with a second visit up to one month after the first if needed. At the time of the first visit, written consent was obtained from the patient and/or the patients’ parent/caregiver. Figure 1 is a schematic of the trial design and logistics.

Figure 1: Schematic of the trial design and logistics

Ten surgeons were recruited to participate in the trial (Figure 1, Table 1). They had high volume practices devoted to the care of patients with CL/P and were selected based on their different levels of surgical experience to obtain a broad range of feedback on diagnosis and treatment planning. They were first trained in the use of the SAFS, and then they treatment planned six patients—three lip revision, one non-revision, and two lip repair patients—using the SAFS. For patient safety, and since this was the first-time surgeons used the SAFS to evaluate patients, they were not allowed to evaluate patients from their own Center. Surgeons also were unaware of whether patients in Group 1 were in the revision or non-revision sub-groups (i.e., whether a recommendation was made for revision). To assess agreement among the surgeons, the SAFS of two revision and two repair patients were selected. Four surgeons evaluated one of the revision and repair patients and the other four surgeons evaluated the other revision and repair patients. This approach was needed to ensure that no surgeon evaluated a patient from his/her own Center. Figure 1 is a schematic of the trial design and logistics.

SAFS Presentation and Surgeons’ Interviews

The SAFS standardized facial images of a patient were presented in four sequential Phases. The following demonstrates these phases for a patient slated for lip revision.

Phase 1: 2D facial photographs at rest and at the maximum of different animations (figure 2) https://tufts.box.com/s/c8yf5ot57siyg3odre0un6u67tc3ng66.

Phase 2: 3D facial photographs at rest and at the maximum of different animations https://tufts.box.com/s/77xbh3pgsl9svl4q1l20beyanhaapwyu.

Phase 3: Video recordings of the face during different animations https://tufts.box.com/s/vjyfcz2m3p86qd8lbimnrb88vxuyi0lj.

Phase 4: Dynamic objective measures displayed as visual aids of the face during different animations https://tufts.box.com/s/5436b628hydgc7zja79v9qrrlpp7b22w and vector plots of movements during different animations https://tufts.box.com/s/rlk67gy7rye66tg4bpnwbe1u4f92gfvf.

Figure 2: 2D facial photographs of different facial animations performed for each phase of the SAFS presentation including the 3D photographs, videos and dynamic displays

One researcher (CAT) presented the SAFS to each surgeon. At the end of each Phase (1 to 4), the surgeon was asked to provide a list of problems and goals for surgery. Then, at the completion of the entire SAFS presentation a 45 to 60 minute, semi-structured, one-on-one, in-depth-interview (IDI) was conducted via phone with the surgeon to explore the decision-making process during treatment planning. The interviewer was a clinical psychologist with experience and skill in focused discussions in both corporate research and academic settings. Interview guides were utilized that were inclusive and designed to elicit open-ended discussion. Areas explored were modeled on those identified previously by other surgeons who were involved in the development of the SAFS. All interviews were audiotaped, transcribed, and stripped of identifying data.

The transcripts were analyzed using the Grounded Theory Method (GTM) (Thomson, 2011; Charmaz, 2006; NIH Publication No. 02-5046) whereby themes are induced from open-ended responses rather than from a priori conceptual categories. Making sense of complex interview data via GTM mitigates researcher bias and supports openness to results not expected beforehand (Glaser & Strauss, 1967), as under Burawoy’s “extended case method” (Burawoy, 1991; 1998; Nelson, 2009). ATLAS. ti statistical software (NSF, 1997; Patton, 1990) was used to label, categorize, and sort the large amounts of interview data tagged through open coding. Codes then were iteratively associated with core code categories based on centrality to a code group topic. Based on the method of constant comparison, stopping occurred at the point of theoretical saturation. Topical reports then were generated based on the surgeons' quotations collected in code groups. The sample size calculation in qualitative research is set at the point when the data collected reveals no new themes/concepts or patterns (theoretical saturation). As such, there is no clear consensus on appropriate sample sizes; however, evidence suggests that saturation generally occurs between 10 and 30 interviews (Thomson, 2011).

Patients were recruited between January 2018 and 2020. Forty-eight of 49 patients completed the SAFS data-collection—one patient was lost to follow-up (Table 2). Two surgeons, both from the same Center, did not evaluate any patients, therefore, eight surgeons (female=6, male=2) completed the study. Because a subgroup of SAFS was repeated with the surgeons, only 36 of the 48 patient SAFS (Table 2) were used for the surgeon interviews. The additional 12 SAFS provided a pool from which, as far as possible, the patients selected to present to the surgeons were balanced by cleft lip type (unilateral versus bilateral).

| All Patients Enrolled with SAFS Data (n=48) | ||||||

| Age | Male | Female | Unilateral | Bilateral | Total | |

| Surgery Type | ||||||

| Revision (yrs.) | 12.2±4.8 | 13 | 8 | 15 | 6 | 21 |

| Non-Revision (yrs.) | 14.0±2.7 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 10 |

| Repair (mos.) | 3.1±0.8 | 13 | 4 | 10 | 7 | 17 |

| Total | 31 | 17 | 30 | 18 | 48 | |

| Patients whose SAFS Data were used by Surgeons (n=36) | ||||||

| Age | Male | Female | Unilateral | Bilateral | Total | |

| Surgery Type | ||||||

| Revision (yrs.)* | 11.9±4.7 | 11 | 7 | 13 | 5 | 18 |

| Non-Revision (yrs.) | 13.7±3.0 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| Repair (mos.)** | 3.1±0.8 | 7 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 10 |

| Total patients | 22 | 14 | 25 | 11 | 36 | |

* Two patients SAFS from the 48 revision patients were shown to the same surgeons.

** Two patients SAFS from the 17 repair patients were shown to the same surgeons.

Table 2. Patient Demographics

Critical constructs of the qualitative analyses included patient type (infant and child), type of surgery (revision, non-revision, and repair), CL±P (unilateral and bilateral), and surgeon agreement (repeated patients SAFS). The themes generated represent diversity by these constructs and enabled comparison of the main construct of interest to the surgical decision-making processes of the surgeons. Because there is no objective measure for "importance" of a theme, the results are ordered by the theme with the greatest number of quotations presented first. For each theme a sampling of illustrative surgeon quotations is provided to lend richness to the analysis. Based on the analysis, common themes emerged from the IDIs when the surgeons were engaged in treatment planning for lip revision (Table 3) and primary lip repair (Table 4) with the use of the SAFS. Thus, the null hypothesis as cited was rejected.

| Common Themes (Lip Revision) |

| 1. When it comes to facial/lip revision surgery timing is everything |

| 2. All procedures involve risks and limitations |

| 3. The treatment plan should follow patient and family goals |

| 4. Plan ahead for the maneuvers that will be done during surgery |

| 5. Muscle repair is tricky and options are limited |

| 6. Scarring is a major consideration in planning for surgery |

| 7. Results of lip (& nasal) revision will be evident and beneficial from several aspects—appearance, speech, and psychosocially |

| 8. Multiple surgeries are needed |

| 9. Orthodontics/alveolar bone grafting and orthognathic surgery affect revision surgical planning |

10. Treatments impacted by surgeons’ resources 11. Other (less discussed themes) - Realistic expectations must be set - Post-operative family and patient cooperation is important - Some diagnoses and treatments are fairly standard - Surgeons differ in surgical procedures they recommend - Asymmetry is a common problem that can be fixed with surgery - Effects of surgery on breathing must be a primary concern - Not everything requires surgery - Some things are discovered intraoperatively - Ethnicity matters |

Table 3: Common themes recognized in surgeons’ decisions for lip revision surgery.

| Common Themes (Lip Repair) |

| 1. Use of nasal alveolar molding (NAM) has pros and cons and there are alternatives |

| 2. Working closely with the family is important |

| 3. Diversity among patients impacts diagnosis, planning, and outcomes |

| 4. Soft tissue work has special considerations |

| 5. Lip repair surgery has risks and limitations |

| 6. Different surgeons take different approaches to treatment |

| 7. Other (less discussed themes) |

| - Live infant examinations provide important tactile information |

| - Telehealth is limited compared with face to face patient examination |

Table 4: Common themes recognized in surgeons decisions for lip repair surgery.

(1) Lip Revision Surgery

Theme 1. When It Comes To Lip Revision Surgery, Timing Is Everything

By far the most numerous comments revolve around the importance of the best timing for surgery. There is an expectation that a sequence of multiple surgeries or treatment interventions will be required (e.g., sometimes multiple staged revisions, orthodontics, alveolar bone grafting, jaw surgery, etc.). Ideally it is better to wait until craniofacial growth is complete—at approximately 17 to 18 years in males and slightly earlier in females—before doing jaw surgery, if needed, and /or aggressive nasal surgery such as rhinoplasty to correct the nasal dorsum and/or nasal septal deviation (septorhinoplasty). Often, septal deviation causes breathing issues in patients. Jaw surgery is generally a maxillary advancement but in certain instances the mandible also may be set back depending on the patient’s facial structure. In addition, it is preferred that alveolar bone grafting and jaw surgery be completed before definitive nasal work/rhinoplasty. If nasal work is done in childhood, it is best limited to less aggressive procedures such as columella lengthening, nasal tip adjustments, and/or adjustments to the nasal sills for symmetry—work that has limited effects on the nasal cartilage because the cartilage may have remaining growth potential. When a child has functional needs (e.g., breathing problems) and/or psychosocial issues (e.g., being teased, a burning desire for a correction), however, surgeons may consider doing a lip/nasal revision at or around the time of bone grafting (~ 6 to 12 years). Even then, it is preferred to delay the revision until at least 6 months after alveolar bone grafting because of residual swelling.

Theme 2. All Procedures Involve Risks And Limitations

The second-most discussed theme revolves around the risks of the surgical procedures and the limits to what is surgically possible. The risk of patients needing multiple surgeries is mentioned most-commonly. Specifically, surgeons are aware of the short-term risks of multiple surgeries (e.g., bleeding, infection, risk of a cartilage graft becoming necrotic) and they recognize long-term effects that negatively impact midfacial growth resulting in midfacial deficiency. Bilateral cleft lip revision is considered particularly risk prone. Scarring is considered a common risk for the lip and nose which may result in impaired movements, hypertrophic tissue in the lip, and a negative impact on nasal growth. Hypertrophic tissue is particularly a problem in patients with darker skin color. Another risk is the possible adverse impact on speech that results from midfacial advancement surgery in later adolescence leading to a possible worsening of hypernasality—patients should be informed of this possibility. Surgeons are mindful that relapse is always possible especially after jaw surgery, and therefore as far as possible, this surgery should be delayed until craniofacial growth has stabilized. With soft tissue surgery, when things do go wrong it can be very difficult to pinpoint the reason (e.g., poor lip movement after surgery). Some surgeons express the view that surgically altering lip movement in a predictable manner is not possible. They recognize that surgical perfection is near impossible in this patient population and sometimes even an ‘improvement’ may not be possible, and stretching the limits of surgery, for example, aggressive surgery, may lead to dangers of surgical overreach.

Theme 3. The Treatment Plan Should Follow Patient And Family Goals

The third-most discussed theme centered on the need to place the patient and family goals first. Surgical decisions should be guided by the patient and family as their needs are often subjective and family specific. If the patient/family do not perceive an issue with the lip and/or nose then in most instances no interventions are necessary, alternatively, if a problem is perceived then attempts are made to address it. Although improvement in appearance is ideal, patient and parent satisfaction with the surgical outcomes is primary. Surgeons recognize the need to strive for family and patient consensus on treatment, especially the patient’s concerns which drive the expected treatment. Involving the patient and family in treatment decisions early, and discussing options for surgery in a non-directive manner are key. Re-confirming the treatment with the patient and family immediately pre-operatively is advised.

Theme 4. Plan Ahead For The Maneuvers That Will Be Done During Surgery

There is universal agreement among surgeons on the importance of pre-surgical planning. The surgeons provide several patient specific surgical planning summaries, though only one is quoted below, this theme was the fourth-most discussed in the transcripts. They note the importance of planning maneuvers such as manipulating and/or grafting nasal cartilage and augmenting soft tissue. While the patient is under anesthesia fine measurements can be made to address asymmetries, and surgical markings can be drawn to assist with maneuvers such as columella lengthening and adjusting the philtrum width.

Theme 5. Muscle Repair Is Tricky And Options Are Limited

Issues related to the musculature and muscle repair are the fifth-most discussed theme. In part, this reflects the fact that the SAFS dynamic technology used by surgeons brought attention to movement issues that may not be apparent in the 2D and 3D images. Surgeons feel that they can address static lip form such as, for example, increasing or decreasing lip height or width to improve symmetry or replacing scar tissue but are limited in their muscle repair techniques to address directionality of soft tissue movement and even at times to completely re-approximate the muscle tissues. The lack of muscle tissue can severely limit movements—for example in a patient with a bilateral CL/P there may be limited muscle in the prolabium that results in a “tight appearance of the upper lip” post surgically. In most instances, revision is feasible, but when it is not, there may be alternatives—e.g., use of Botox to enhance or balance lip symmetry and/or facial physical therapy with biofeedback guidance to enhance facial expressive behaviors.

Theme 6. Scarring Is A Major Consideration In Planning For Surgery

Scarring is not just a risk factor for surgery, it is also a major treatment issue. Treatment of scarring is the sixth-most extensively discussed theme in the study. Scar revision surgery may improve appearance, but past scarring in a patient usually predicts future scarring, and there is a trade-off between scar removal (e.g., with a full thickness lip revision) and leaving sufficient tissue for movement. Moreover, when a patient has had multiple lip revisions, surgeons are more cautious when contemplating doing another due to the greater difficulty in getting a successful result. Thus, revision to remove scar tissue is not for everyone as described in the quote below. Non-surgical options to minimize scarring that include fat and /or Botox injections into the lip are mentioned.

Themes 7-10 are summarized briefly below with illustrative surgeon quotations.

Theme 7. Results Of Lip (& Nasal) Revision Will Be Evident And Beneficial From Several Aspects—Appearance, Speech, and Psychosocially

Theme 8. Multiple Surgeries Are Needed

Theme 9. Orthodontics/Alveolar Bone Grafting And Orthognathic Surgery Affect Revision Surgical Planning

Theme 10. Treatments Are Impacted By Surgeon And Patient Resources

A variety of other less-discussed sub-themes emerge from surgeons’ responses some of which were discussed earlier in different contexts. Examples of these sub-themes include setting realistic expectations for surgical outcomes with the patient and family and emphasizing that postoperatively their cooperation is important to ensure the desired result. Related to the surgeons and the surgery is the recognition that some diagnoses and treatments are standard, however, surgeons may differ in the specific surgical revision procedures that they perform. Asymmetry is a common issue that can be fixed with surgery, the effects of surgery on breathing must be a primary concern, and not every clinical situation requires surgery. Surgeons are trained to expect the unexpected as some issues are discovered intraoperatively. Lastly, ethnicity as a patient characteristic also affects surgeons’ decision-making.

(2) Primary Lip Repair Surgery

Theme 1. Use Of Nasal-Alveolar Molding (NAM) Has Pros And Cons And There Are Alternatives

Discussion around nasal alveolar molding (NAM) which is a specific type of infant orthopedic (IO) technique used immediately prior to lip repair is by far the single most-discussed theme with an extent three times that of the second-most discussed theme (Theme 2: Working with the Family). Since NAM is a leading treatment strategy for infants born with CL/P, it is not surprising it emerged as the foremost theme. Generally, the primary lip and nasal repair are done at the same time. Surgeons described the NAM as a common strategy for shaping the nose and specifically molding/elongating the columella prior to the lip repair. This is especially the case for a baby with a bilateral CL/P where the cleft segments are separated and there is a protrusive premaxilla. In such a case, soft tissue work becomes more difficult and special considerations of using infant orthopedics to realign the premaxilla prior to lip repair is preferred. The device includes a palatal plate with attached nasal stent(s) or struts that exert a ‘push’ force from the palatal plate to mold the nasal cartilage. Surgeons expressed the view that NAM may limit the number of future operations for a patient. It is best that treatment with NAM starts during the first few weeks after birth when nasal cartilage is most amenable to molding, however, NAM is just one possible IO appliance and there are others used by surgeons. Two other examples mentioned are the DynaCleft and the Latham appliance. The DynaCleft nasal elevator adheres to the forehead with a hook around the dome of the nasal cartilage to elevate (exert a pull force) and mold the cartilage mentioned for. Advantages mentioned for this appliance are that it is more versatile because it can be used in conjunction with other IO appliances and the nasal molding can be initiated earlier in life than for the NAM. The Latham appliance is a pin-retained plate that requires a brief general anesthesia to be placed in the mouth. Surgeons’ choice of appliance may be family dependent. The NAM requires many clinic visits for adjustment and depending on the parents’ resources and ease of accessibility to the clinic, it may or not be the best choice for certain families. Because the Latham appliance may is fixed to the palate and requires less visits, it may be a better choice when clinic accessibility is an issue. Also, there may be improvements feeding infants with these appliances.

Surgeons recognize some risks and drawbacks to NAM. These include skin irritation in the infant, and for both the clinician and parents, there is a significant time investment and a steep learning curve when the appliance is used. For example, clinicians need to make frequent adjustments to the palatal plate and nasal stent(s) of the appliance and parents need to be compliant with NAM for a successful outcome. Feeding is a possible risk initially, especially at the time that the nasal stents are placed but it is only a temporary risk until the parents become adept using the appliance.

Theme 2. Working Closely With The Family Is Important

Working with the parents toward realistic expectations—expectations with regard to the surgery itself and the outcome of surgery is the second-most discussed theme. When discussing surgery, the conversation is kept non-technical and focuses on goals (e.g., making the lip continuous, improving the shape of the nasal tip), and what to expect after the surgery (e.g., expect a baby with a very different face). It is important to take steps to reassure the family regarding the immediate surgery—such as what happens when they arrive on the day of the surgery, where they will stay during the surgery, the duration of the surgery—and provide general support. There are parental support groups, for example, the American Cleft Palate Association’s Cleft Line provides valued resources for questions regarding expectations around the surgery. Accommodating the family and letting them make decisions where possible (e.g., whether to use the NAM) is preferred. Overall, surgeons find that families generally view the outcome of lip repair surgery favorably.

Theme 3. Diversity Among Patients Impacts Diagnosis, Planning, And Outcomes

Every infant requiring a lip repair presents a unique challenge. One learns from previous cases, but every case provides new challenges that may require a variation on the surgical technique. Surgeons find these surgical challenges inspiring. At times, only when the patient is asleep or anesthetized can a proper evaluation be accomplished. Age is a consideration in the infant—it is best for the infant to be strong, healthy, and gaining weight, and delaying surgery until these factors are achieved is important. Race is another factor that affects the surgical selection during the planning stage.

THEME 4. SOFT TISSUE WORK HAS SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

There are multidimensional aspects and nuances to the soft tissue work for an adequate lip repair when bone is involved. For example, in the patient with a bilateral CL/P who has a protrusive pre-maxilla repair may be technically difficult because stretching of tissues is involved to achieve an adequate repair. When repairing a wide cleft where a lot of bone is missing one surgeon described the surgical approach as “trampolining that soft tissue across this big gap” where eventually over time because of a lack of bone support the soft tissue sags. Invariably, these infants will need a lip revision later in life but there is an awareness that further surgery increases the possibility of increased scarring leading to possible abnormal lip lengths and asymmetry.

Theme 5. Lip Repair Surgery Has Risks And Limitations

As expected, primary lip repair surgery is not entirely predictable and involves risks and the possibility of relapse. Structural changes occur as the infant ages and scarring becomes more obvious. Surgeons note the importance of properly placed incisions at the time of the lip repair to mitigate visible scarring later in life. When it comes to relapse, the nasal cartilage is particularly prone.

Theme 6. Different Surgeons Take Different Approaches To Treatment

The surgeons differ on the technique they use for lip repair and that is partly dependent on their training. The techniques mentioned include the Fisher and Millard as well as modifications thereof.

Theme 7. Other

Other sub-themes mentioned for primary lip repair are the importance of ‘live infant examinations’ especially as it pertains to tactile information—manipulating the circumoral tissues is very informative. Telehealth was mentioned as having advantages perhaps for initial consultations but being limited compared with ‘face to face’ examinations.

| Diagnosis and Treatment Planning | ||||

| Statements by Surgeons (Patient 1) | Four Surgeons Coded A to D | |||

| A | B | C | D | |

| No obvious scarring needing surgery | x | |||

| Lip height good | x | |||

| Dent in red lip so soft tissue deficient and lip revision recommended now | x | x | x | x |

| Upper lip too tight, causes pouting effect | x | |||

| Upper jaw set back, needs jaw surgery, orthognathic correction | x | x | x | |

| Braces maybe alternative to jaw surgery | x | |||

| Cheek puff/pucker does not warrant surgery | x | |||

| Nasal asymmetry, to be addressed later to correct nasal tip | x | x | x | |

| Would do some nasal work now | x | |||

| Statements by Surgeons (Patient 2) | Four Surgeons Coded E to F | |||

| E | F | G | H | |

| Abnormal wet mucosa in upper lip should be inside mouth; upper lip abnormally thick surgery needed | x | x | ||

| Skin tethering scar affecting upper lip, muscle surgery may be required | x | |||

| Prominent lip scar can be dealt with using fat graft | x | |||

| Nasal asymmetry between nostrils, bone graft and rhinoplasty needed | x | x | x | |

| Septorhinoplasty needed when growth is complete | x | x | ||

| Lip revision not needed | x | |||

Table 5: Surgeons’ agreement for lip revision diagnosis and treatment planning using the SAFS.

(3) Agreement Among Surgeons’ Treatment Planning Decisions

Lip Revision

To assess surgeon agreement on diagnosis and treatment planning decisions, two approaches were used. For the first approach, each surgeon completed the SAFS for one non-revision patient. The surgeons did not know who the non-revision patients were, and they would be expected to not recommend surgery for these patients. Specifically, seven of the eight surgeons did not recommend surgery although in some cases there was a recommendation for minor surgical work. For the second approach, four surgeons evaluated the SAFS for one revision patient and the other four evaluated the SAFS for a second revision patient. Each of the surgeons who reviewed the patient’s SAFS provided largely the same basic diagnoses/treatments. Table 5. lists the statements for each patient ("x" indicates the surgeon identified in the column header made the given statement). Because interviews were semi-structured with interviewer prompts varying by surgeon, the absence of an "x" does not indicate disagreement with a statement but rather absence of information from the surgeon. For Patient 1, all four surgeons recommended further lip revision and three recommended nasal tip surgery. One surgeon [D] felt the need for work on nasal asymmetry. For Patient 2, three of the four surgeons recommended lip revision, (E, F (fat graft), G), and the other surgeon (H) recommended nasal work only. Three surgeons mentioned the need to address nasal asymmetry which was not addressed by one surgeon (F).

Lip Repair

Refusing to perform a lip and or palate repair in an infant is not an option, thus, the focus is on agreement around nuances of the repair. Four surgeons evaluated the SAFS for one infant and the other four evaluated the SAFS for a second. Both infants had an unrepaired bilateral CL/P. The surgeons provided largely the same basic diagnoses/treatments for each (Table 6). For Infant 1, three of the four surgeons recommended Lengthening the columella, removal of lower lip pits, and pre-surgical infant orthopedics prior to the surgery. Two surgeons also recommended some form of rhinoplasty to address asymmetry and nasal tip issues. For Infant 2, all four surgeons recommended rhinoplasty to address narrowing of alar bases, reshaping of nostrils, and lengthening of the columella and one surgeon recommended removal of an excess skin nubbin. No surgeon made a recommendation contrary to that of another.

| Diagnosis and Treatment Planning | ||||

| Statements by Surgeons (Patient 1) | Four Surgeons Coded A to D | |||

| A | B* | C | D | |

| Rhinoplasty (asymmetry, nasal tip) needed | x | x | ||

| Diminutive columella needs work | x | x | x | |

| Protrusive premaxilla and prolabium needs work | x | x | x | |

| Lower lip pits need removal | x | x | x | |

| Pre-surgical orthopedic device needed (NAM or Latham) | x | x | x | |

| Statements by Surgeons (Patients 2) | Four Surgeons Coded E to H | |||

| E | F | G | H | |

| Rhinoplasty indicated (alar bases should be narrower, reshape nostrils) | x | x | x | x |

| Excess skin nubbin | x | |||

| Columella/upper lip needs lengthening | x | x | x | x |

* No comments for B

Table 6: Surgeons’ agreement for lip repair diagnosis and treatment planning using the SAFS.

A wide variety of common themes emerged from the interviews with surgeons regarding the decision-making process for CL/P surgery that reflect the pervasiveness of these decisions. At nearly every stage of treatment decisions are made: Some in conjunction with patients/families, others with the CL/P team, and still others by the surgeon alone. Reviewing the numerous and varied considerations that characterize the decision process is useful both for trainees and experienced practitioners. For surgeons in training, a methodical and inclusive review of the considerations is of obvious benefit. And for surgeons actively involved in cleft care, a comprehensive list of considerations that comprise each surgical decision is helpful—if for no other reason than ensuring each decision is well-reasoned and given thorough weight. To this end, the surgical considerations that emerged provide useful and comprehensive information to populate checklists (Tables 7 & 8) for the CL/P surgeon and her team that would be a valuable resource and a first step for those surgeons seeking to develop a structured process for making surgical decisions. A comparative review of the surgeons’ ‘top five’ themes demonstrates a difference in emphasis of the considerations by patient type (revision and repair); however, three themes emerged as common to both types, ‘working closely with the parents/family’, ‘risks and limitations of surgery’, and ‘soft tissue considerations/muscle repair’. Soft tissue and other considerations were explored in depth earlier, however, interactions with the patient/family and the risks and limitations of surgery warrant further consideration.

Decisions made by surgeons in conjunction with the patient and parent/ caregiver—shared decision making—occurs when patients/parents and providers collaborate to develop a mutually agreed treatment plan (Legare et al., 2014). It brings quality to the decision-making process over and above the decision itself (Shaw et al., 2020). In a systematic literature review of shared decision making on patient choice for elective general surgical procedures, Boss and co-workers (Boss et al., 2016) found that although this shared process may reduce or have no impact on patient choice for elective surgery, it may promote a more positive health care experience and decision-making process for the patients. Lip revision in patients with CL/P is an elective surgery, and these patients and their families want to participate in surgical decisions but may have limited understanding of their facial difference and the surgical indications (Bennett et al., 2020). Surgeons must educate their patients and facilitate the decision-making process (Bennett et al., 2020). The surgeons in this study emphasized the importance of doing just that.

When considering the ‘risk and limitations of surgery’, once again the focus is different depending on patient type. Specifically, primary lip repair in an infant is a forgone conclusion and surgeons can only hope to lessen and/or avoid risks when possible. Alternatively, the choice of doing a lip revision is intertwined with the surgical consequences in the form of the risks and the limitations.

In this instance, the patient/family and surgeon have a choice of whether and when to perform the surgery based on the surgeon’s expert decisions. Cooper and co-workers (Cooper et al., 2020) in a sample of 882 patients found that 15% of patients had deficits in knowledge of their diagnosis and /or procedure. Once surgeons identify the surgical risks, knowledge deficits in patients/families surrounding the risks and limitations of the surgery must be avoided and identifying patients that are particularly prone to such deficits is important to facilitate high-quality decisions by patients/families and surgeons alike. For surgeons, adequate surgical preparation and planning can help avoid negative surprises associated with the surgical procedure. A thorough clinical examination of the patient coupled with a systematic planning process like the SAFS and checklists of factors to be addressed as demonstrated in this study help to maximize positive outcomes. These checklists can be tailored for use by any clinician.

| Lip Revision Checklist | |

| Question | Answers/Considerations |

From your perspective, is this the best time for Lip revision Nasal revision Alveolar bone grafting Jaw surgery * Might previous lip and nasal surgery impact your outcome? * Could speech be affected by the planned surgery? | |

Surgical risks. Is your patient particularly prone to: Excess bleeding, infection, occurrence of necrotic tissue Worsening of scars Development of hypertrophic tissue Increased hypernasality The need for jaw surgery (midfacial advancement) Relapse If you said yes to any of these, what leads you to believe this could be a specific risk for your patient? How aggressive are your surgical plans? (Rate from 1-10, with 10 being most aggressive) Why does your plan deserve this rating? | |

Patient and family goals. What are the patient’s concerns/goals (elicit in own words)? What are the family’s concerns/goals (elicit in own words)? Do the patient and family concerns/goals match? If not, how will you reconcile differences? What areas of the face bother the patient? Are there any psychological concerns from the patient and/or family perspective? How will you manage these concerns? | |

Which specific facial areas do you plan to address/improve with surgery and describe why? Upper lip length? Describe. Upper lip width? Describe. Upper lip symmetry? Describe. Increase/decrease the upper lip thickness? Describe. Lengthen the columella? Describe. Restore cupids bow? Describe. Adjust lower lip form? Describe. Any additional areas? | |

Which specific facial movements do you plan to address/improve with surgery and why? Upper lip vertical movement? Describe. Upper lip horizontal movement? Describe. Lower lip movement? Describe. Any other facial movements? | |

Plans for the actual surgery (pre-surgical planning). Do you have adequate muscle for the revision? Describe. Map out the surgical maneuvers for: Soft tissue lip/augmentation Soft tissue nose/augmentation Manipulating/grafting nasal cartilage Alveolar bone grafting, if it is to be done at the same time | |

Scar tissue. Do you plan to revise the scar at the time of the surgery? How will you manage the effect of: Prior scarring and its effect on the outcome? Multiple previous surgeries and its effect on the muscle and the outcome? Multiple previous surgeries and its effect on the muscle? Other non-surgical options? e.g., laser, fat injection, Botox. How will the patient’s age impact your surgery? Will you make direct measurements/markings on the patient’s face while the patient is under anesthesia? Will you reconfirm the surgical plan with the family on the day of, and immediately before, the surgery? | |

Do you think that additional surgeries will be needed for your patient in the future? If yes, expand. Could future orthognathic surgery needs affect the revision outcomes? If so, describe. | |

Are there treatments unavailable to you in your clinic e.g., laser therapy, that might be beneficial alternative for this patient’s soft tissue problems? | |

Have you set realistic expectations for the patient/family? Please describe how you set those expectations? | |

How have you assessed the family’s comprehension and motivation to comply with post-surgical care at home? | |

Have you arranged for additional support to assist the family in executing a post-surgical home care plan? | |

| How is the patient’s ethnicity affecting your surgical plans? | |

Table 7: Lip revision checklist.

| Lip Repair Checklist | |

| Question | Answers/Considerations |

Pre-surgical infant orthopedics (IO). Do you plan to use an IO appliance. If yes, which will you use and why? NAM Latham DynaCleft Another type of IO appliance (please specify). Will you combine appliances? Why? Did you discuss with the family the advantages and disadvantages of the chosen appliance(s)? Did you or your team conduct an assessment to discern whether the family can comply with your recommended IO appliance? Or would another appliance would be more suitable for their home situation? What ideal age in months will you start IO on this infant? What are your anatomical expectations for stopping IO treatment on this infant? Do you plan to use the IO appliance after the surgery? Did you provide verbal and written instructions on using the appliance to the family? How have you confirmed that the family understands the instructions? (e.g., teach-back method? Other?) | |

Realistic expectations for the family. How have you set realistic expectations for the family? What are your goals for the lip repair surgery? Have you described the goals to the family in non-technical terms? Have you described to the family how their infant will look after the surgery? Have you reassured the family regarding the surgery itself, e.g., what to expect on the day, where they will stay, who will update them on progress of the surgery, etc? Have you provided the family with information on contact information for support groups, e.g., ACPA’s Cleft Line? | |

Surgery and surgical risks. Is the infant healthy enough to have the surgery? What benchmarks have you used to determine the infant’s overall health? What technique for lip repair will you use and why? How do you plan to minimize the effects of scarring of the lip? Is the patient likely to have greater than expected scarring after surgery and healing? And why do you expect this? Did you make a preliminary assessment as to whether revision surgery will be needed after the initial lip repair? And if so, how did you make that determination? Do you expect relapse of the nasal septal cartilage position as the infant ages? If so, why? When you plan the technique for lip repair surgery, do you consider how it could affect lip movement? | |

Table 8: Lip repair checklist

Although not the main aim of the study, an interesting finding was that the surgeons were reasonably consistent in their recommendations. Past research has demonstrated that when surgeons view the same set of patients, in general they disagree in their recommendation for lip revision (Trotman et al., 2007). In this study, surgeons agreed on most of the clinical observational findings for the same child that they viewed. Perhaps this type of in-depth analysis based on a systematic assessment of extensive images by surgeons improves agreement at the level of clinical diagnostic observations. However, the final recommendation for ‘choosing to do a revision’ may lead to disagreement among surgeons because many other factors are at play that include input from the patient and family regarding the desire to have a surgery; suspicion that scarring may worsen because of multiple surgeries; the degree of surgical experience; confidence that one can deliver a successful result; and other variables. These factors that are unrelated to the surgeon’s actual diagnostic findings may have a greater bearing on the discord among surgeons when the final recommendation for revision surgery is made.

Other Considerations

In March 2020, with the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic Tufts University and University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill suspended research activities for several months. During this time, only virtual, non-patient contact, research activities were approved. At that time, patient recruitment and patient data-collection for the SAFS were complete. The SAFS presentations to the surgeons, which prior to the pandemic were conducted in-person at the surgeons’ respective Craniofacial Centers, were switched to virtual presentations. This change allowed an evaluation of a virtual ‘remote’ platform for treatment planning. Thirty virtual SAFS presentations were conducted, and every surgeon participated in at least one. Most of the surgeons viewed the presentations on a laptop, some used a desktop, and one surgeon viewed one presentation on an iPhone. They rated their experience along a Likert scale as follows: 1 = “unsatisfactory”, 2 = “satisfactory”, 3 = “very satisfactory, I prefer this method”. Overall, the surgeons were very positive on the virtual presentations. They rated 28 of the 30 virtual presentations as a ‘3’ and two were rated a ‘2’. Positive comments were that the process for the presentations felt comfortable; more convenient especially for scheduling viewings; just as efficient as the in-person presentations with the ability to conduct presentations anywhere and anytime; and cost-effective—no travel time needed. Negative comments were the lack of intraoral images and inability to control and move the 3D images; however, for the latter the viewer can instruct the presenter to do this. Also, for three presentations there were minor technical problems that were easily fixed.

There were a few caveats in this study. The surgeon participants were from four large health centers on the east coast and there may be a concern of external validity; however, the surgeons can be said to represent a good balance based on their demographic factors and surgical experience. All were credentialed medical professionals, and all decisions and interviews were based on the SAFS method. Finally, the themes were ranked by the number of associated quotations, and we chose to infer importance based on this rank order. We considered this a logical inference; however, the surgical checklists from this research include all considerations without inferring importance which, in this instance, is left to the surgeon.

This study emphasized factors considered by surgeons when treatment planning for lip surgery, both primary lip surgery and secondary revision surgery, in patients born with cleft lip/palate. The study highlighted the importance of shared decision making with the patient/caregivers to develop a mutually agreed treatment plan for lip surgeries which is a finding of similar studies of other types of surgeries. Differences in the decisions between primary lip repair and lip revision were highlighted especially because lip revision is an elective surgery where there is a choice to perform a lip revision that is intertwined with the surgical consequences in the form of the risks and the limitations. The authors provided checklists of factors/considerations to serve as a guide for surgeons/clinicians.

This article was funded from National Institutes of Health NIDCR branch (Grant # U01 DE024503).

Trotman CA, Faraway J, Bennett ME, Garson GD, Phillips C, Bruun R, Daniel R, David LR, Ganske I, Leeper LK, Rogers-Vizena CR, Runyan C, Scott AR, Wood J. Decision Considerations and Strategies for Lip Surgery in Patients with Cleft lip/Palate: A Qualitative Study. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2023 Apr 21:2023.04.20.23287416. doi: 10.1101/2023.04.20.23287416. PMID: 37131720; PMCID: PMC10153332.

Clearly Auctoresonline and particularly Psychology and Mental Health Care Journal is dedicated to improving health care services for individuals and populations. The editorial boards' ability to efficiently recognize and share the global importance of health literacy with a variety of stakeholders. Auctoresonline publishing platform can be used to facilitate of optimal client-based services and should be added to health care professionals' repertoire of evidence-based health care resources.

Journal of Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Intervention The submission and review process was adequate. However I think that the publication total value should have been enlightened in early fases. Thank you for all.

Journal of Women Health Care and Issues By the present mail, I want to say thank to you and tour colleagues for facilitating my published article. Specially thank you for the peer review process, support from the editorial office. I appreciate positively the quality of your journal.

Journal of Clinical Research and Reports I would be very delighted to submit my testimonial regarding the reviewer board and the editorial office. The reviewer board were accurate and helpful regarding any modifications for my manuscript. And the editorial office were very helpful and supportive in contacting and monitoring with any update and offering help. It was my pleasure to contribute with your promising Journal and I am looking forward for more collaboration.

We would like to thank the Journal of Thoracic Disease and Cardiothoracic Surgery because of the services they provided us for our articles. The peer-review process was done in a very excellent time manner, and the opinions of the reviewers helped us to improve our manuscript further. The editorial office had an outstanding correspondence with us and guided us in many ways. During a hard time of the pandemic that is affecting every one of us tremendously, the editorial office helped us make everything easier for publishing scientific work. Hope for a more scientific relationship with your Journal.

The peer-review process which consisted high quality queries on the paper. I did answer six reviewers’ questions and comments before the paper was accepted. The support from the editorial office is excellent.

Journal of Neuroscience and Neurological Surgery. I had the experience of publishing a research article recently. The whole process was simple from submission to publication. The reviewers made specific and valuable recommendations and corrections that improved the quality of my publication. I strongly recommend this Journal.

Dr. Katarzyna Byczkowska My testimonial covering: "The peer review process is quick and effective. The support from the editorial office is very professional and friendly. Quality of the Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions is scientific and publishes ground-breaking research on cardiology that is useful for other professionals in the field.

Thank you most sincerely, with regard to the support you have given in relation to the reviewing process and the processing of my article entitled "Large Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of The Prostate Gland: A Review and Update" for publication in your esteemed Journal, Journal of Cancer Research and Cellular Therapeutics". The editorial team has been very supportive.

Testimony of Journal of Clinical Otorhinolaryngology: work with your Reviews has been a educational and constructive experience. The editorial office were very helpful and supportive. It was a pleasure to contribute to your Journal.

Dr. Bernard Terkimbi Utoo, I am happy to publish my scientific work in Journal of Women Health Care and Issues (JWHCI). The manuscript submission was seamless and peer review process was top notch. I was amazed that 4 reviewers worked on the manuscript which made it a highly technical, standard and excellent quality paper. I appreciate the format and consideration for the APC as well as the speed of publication. It is my pleasure to continue with this scientific relationship with the esteem JWHCI.

This is an acknowledgment for peer reviewers, editorial board of Journal of Clinical Research and Reports. They show a lot of consideration for us as publishers for our research article “Evaluation of the different factors associated with side effects of COVID-19 vaccination on medical students, Mutah university, Al-Karak, Jordan”, in a very professional and easy way. This journal is one of outstanding medical journal.

Dear Hao Jiang, to Journal of Nutrition and Food Processing We greatly appreciate the efficient, professional and rapid processing of our paper by your team. If there is anything else we should do, please do not hesitate to let us know. On behalf of my co-authors, we would like to express our great appreciation to editor and reviewers.

As an author who has recently published in the journal "Brain and Neurological Disorders". I am delighted to provide a testimonial on the peer review process, editorial office support, and the overall quality of the journal. The peer review process at Brain and Neurological Disorders is rigorous and meticulous, ensuring that only high-quality, evidence-based research is published. The reviewers are experts in their fields, and their comments and suggestions were constructive and helped improve the quality of my manuscript. The review process was timely and efficient, with clear communication from the editorial office at each stage. The support from the editorial office was exceptional throughout the entire process. The editorial staff was responsive, professional, and always willing to help. They provided valuable guidance on formatting, structure, and ethical considerations, making the submission process seamless. Moreover, they kept me informed about the status of my manuscript and provided timely updates, which made the process less stressful. The journal Brain and Neurological Disorders is of the highest quality, with a strong focus on publishing cutting-edge research in the field of neurology. The articles published in this journal are well-researched, rigorously peer-reviewed, and written by experts in the field. The journal maintains high standards, ensuring that readers are provided with the most up-to-date and reliable information on brain and neurological disorders. In conclusion, I had a wonderful experience publishing in Brain and Neurological Disorders. The peer review process was thorough, the editorial office provided exceptional support, and the journal's quality is second to none. I would highly recommend this journal to any researcher working in the field of neurology and brain disorders.

Dear Agrippa Hilda, Journal of Neuroscience and Neurological Surgery, Editorial Coordinator, I trust this message finds you well. I want to extend my appreciation for considering my article for publication in your esteemed journal. I am pleased to provide a testimonial regarding the peer review process and the support received from your editorial office. The peer review process for my paper was carried out in a highly professional and thorough manner. The feedback and comments provided by the authors were constructive and very useful in improving the quality of the manuscript. This rigorous assessment process undoubtedly contributes to the high standards maintained by your journal.

International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews. I strongly recommend to consider submitting your work to this high-quality journal. The support and availability of the Editorial staff is outstanding and the review process was both efficient and rigorous.

Thank you very much for publishing my Research Article titled “Comparing Treatment Outcome Of Allergic Rhinitis Patients After Using Fluticasone Nasal Spray And Nasal Douching" in the Journal of Clinical Otorhinolaryngology. As Medical Professionals we are immensely benefited from study of various informative Articles and Papers published in this high quality Journal. I look forward to enriching my knowledge by regular study of the Journal and contribute my future work in the field of ENT through the Journal for use by the medical fraternity. The support from the Editorial office was excellent and very prompt. I also welcome the comments received from the readers of my Research Article.

Dear Erica Kelsey, Editorial Coordinator of Cancer Research and Cellular Therapeutics Our team is very satisfied with the processing of our paper by your journal. That was fast, efficient, rigorous, but without unnecessary complications. We appreciated the very short time between the submission of the paper and its publication on line on your site.

I am very glad to say that the peer review process is very successful and fast and support from the Editorial Office. Therefore, I would like to continue our scientific relationship for a long time. And I especially thank you for your kindly attention towards my article. Have a good day!

"We recently published an article entitled “Influence of beta-Cyclodextrins upon the Degradation of Carbofuran Derivatives under Alkaline Conditions" in the Journal of “Pesticides and Biofertilizers” to show that the cyclodextrins protect the carbamates increasing their half-life time in the presence of basic conditions This will be very helpful to understand carbofuran behaviour in the analytical, agro-environmental and food areas. We greatly appreciated the interaction with the editor and the editorial team; we were particularly well accompanied during the course of the revision process, since all various steps towards publication were short and without delay".

I would like to express my gratitude towards you process of article review and submission. I found this to be very fair and expedient. Your follow up has been excellent. I have many publications in national and international journal and your process has been one of the best so far. Keep up the great work.

We are grateful for this opportunity to provide a glowing recommendation to the Journal of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy. We found that the editorial team were very supportive, helpful, kept us abreast of timelines and over all very professional in nature. The peer review process was rigorous, efficient and constructive that really enhanced our article submission. The experience with this journal remains one of our best ever and we look forward to providing future submissions in the near future.

I am very pleased to serve as EBM of the journal, I hope many years of my experience in stem cells can help the journal from one way or another. As we know, stem cells hold great potential for regenerative medicine, which are mostly used to promote the repair response of diseased, dysfunctional or injured tissue using stem cells or their derivatives. I think Stem Cell Research and Therapeutics International is a great platform to publish and share the understanding towards the biology and translational or clinical application of stem cells.

I would like to give my testimony in the support I have got by the peer review process and to support the editorial office where they were of asset to support young author like me to be encouraged to publish their work in your respected journal and globalize and share knowledge across the globe. I really give my great gratitude to your journal and the peer review including the editorial office.

I am delighted to publish our manuscript entitled "A Perspective on Cocaine Induced Stroke - Its Mechanisms and Management" in the Journal of Neuroscience and Neurological Surgery. The peer review process, support from the editorial office, and quality of the journal are excellent. The manuscripts published are of high quality and of excellent scientific value. I recommend this journal very much to colleagues.

Dr.Tania Muñoz, My experience as researcher and author of a review article in The Journal Clinical Cardiology and Interventions has been very enriching and stimulating. The editorial team is excellent, performs its work with absolute responsibility and delivery. They are proactive, dynamic and receptive to all proposals. Supporting at all times the vast universe of authors who choose them as an option for publication. The team of review specialists, members of the editorial board, are brilliant professionals, with remarkable performance in medical research and scientific methodology. Together they form a frontline team that consolidates the JCCI as a magnificent option for the publication and review of high-level medical articles and broad collective interest. I am honored to be able to share my review article and open to receive all your comments.

“The peer review process of JPMHC is quick and effective. Authors are benefited by good and professional reviewers with huge experience in the field of psychology and mental health. The support from the editorial office is very professional. People to contact to are friendly and happy to help and assist any query authors might have. Quality of the Journal is scientific and publishes ground-breaking research on mental health that is useful for other professionals in the field”.

Dear editorial department: On behalf of our team, I hereby certify the reliability and superiority of the International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews in the peer review process, editorial support, and journal quality. Firstly, the peer review process of the International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews is rigorous, fair, transparent, fast, and of high quality. The editorial department invites experts from relevant fields as anonymous reviewers to review all submitted manuscripts. These experts have rich academic backgrounds and experience, and can accurately evaluate the academic quality, originality, and suitability of manuscripts. The editorial department is committed to ensuring the rigor of the peer review process, while also making every effort to ensure a fast review cycle to meet the needs of authors and the academic community. Secondly, the editorial team of the International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews is composed of a group of senior scholars and professionals with rich experience and professional knowledge in related fields. The editorial department is committed to assisting authors in improving their manuscripts, ensuring their academic accuracy, clarity, and completeness. Editors actively collaborate with authors, providing useful suggestions and feedback to promote the improvement and development of the manuscript. We believe that the support of the editorial department is one of the key factors in ensuring the quality of the journal. Finally, the International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews is renowned for its high- quality articles and strict academic standards. The editorial department is committed to publishing innovative and academically valuable research results to promote the development and progress of related fields. The International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews is reasonably priced and ensures excellent service and quality ratio, allowing authors to obtain high-level academic publishing opportunities in an affordable manner. I hereby solemnly declare that the International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews has a high level of credibility and superiority in terms of peer review process, editorial support, reasonable fees, and journal quality. Sincerely, Rui Tao.

Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions I testity the covering of the peer review process, support from the editorial office, and quality of the journal.

Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions, we deeply appreciate the interest shown in our work and its publication. It has been a true pleasure to collaborate with you. The peer review process, as well as the support provided by the editorial office, have been exceptional, and the quality of the journal is very high, which was a determining factor in our decision to publish with you.

The peer reviewers process is quick and effective, the supports from editorial office is excellent, the quality of journal is high. I would like to collabroate with Internatioanl journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews journal clinically in the future time.

Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions, I would like to express my sincerest gratitude for the trust placed in our team for the publication in your journal. It has been a true pleasure to collaborate with you on this project. I am pleased to inform you that both the peer review process and the attention from the editorial coordination have been excellent. Your team has worked with dedication and professionalism to ensure that your publication meets the highest standards of quality. We are confident that this collaboration will result in mutual success, and we are eager to see the fruits of this shared effort.

Dear Dr. Jessica Magne, Editorial Coordinator 0f Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions, I hope this message finds you well. I want to express my utmost gratitude for your excellent work and for the dedication and speed in the publication process of my article titled "Navigating Innovation: Qualitative Insights on Using Technology for Health Education in Acute Coronary Syndrome Patients." I am very satisfied with the peer review process, the support from the editorial office, and the quality of the journal. I hope we can maintain our scientific relationship in the long term.

Dear Monica Gissare, - Editorial Coordinator of Nutrition and Food Processing. ¨My testimony with you is truly professional, with a positive response regarding the follow-up of the article and its review, you took into account my qualities and the importance of the topic¨.

Dear Dr. Jessica Magne, Editorial Coordinator 0f Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions, The review process for the article “The Handling of Anti-aggregants and Anticoagulants in the Oncologic Heart Patient Submitted to Surgery” was extremely rigorous and detailed. From the initial submission to the final acceptance, the editorial team at the “Journal of Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions” demonstrated a high level of professionalism and dedication. The reviewers provided constructive and detailed feedback, which was essential for improving the quality of our work. Communication was always clear and efficient, ensuring that all our questions were promptly addressed. The quality of the “Journal of Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions” is undeniable. It is a peer-reviewed, open-access publication dedicated exclusively to disseminating high-quality research in the field of clinical cardiology and cardiovascular interventions. The journal's impact factor is currently under evaluation, and it is indexed in reputable databases, which further reinforces its credibility and relevance in the scientific field. I highly recommend this journal to researchers looking for a reputable platform to publish their studies.

Dear Editorial Coordinator of the Journal of Nutrition and Food Processing! "I would like to thank the Journal of Nutrition and Food Processing for including and publishing my article. The peer review process was very quick, movement and precise. The Editorial Board has done an extremely conscientious job with much help, valuable comments and advices. I find the journal very valuable from a professional point of view, thank you very much for allowing me to be part of it and I would like to participate in the future!”

Dealing with The Journal of Neurology and Neurological Surgery was very smooth and comprehensive. The office staff took time to address my needs and the response from editors and the office was prompt and fair. I certainly hope to publish with this journal again.Their professionalism is apparent and more than satisfactory. Susan Weiner

My Testimonial Covering as fellowing: Lin-Show Chin. The peer reviewers process is quick and effective, the supports from editorial office is excellent, the quality of journal is high. I would like to collabroate with Internatioanl journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews.

My experience publishing in Psychology and Mental Health Care was exceptional. The peer review process was rigorous and constructive, with reviewers providing valuable insights that helped enhance the quality of our work. The editorial team was highly supportive and responsive, making the submission process smooth and efficient. The journal's commitment to high standards and academic rigor makes it a respected platform for quality research. I am grateful for the opportunity to publish in such a reputable journal.

My experience publishing in International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews was exceptional. I Come forth to Provide a Testimonial Covering the Peer Review Process and the editorial office for the Professional and Impartial Evaluation of the Manuscript.

I would like to offer my testimony in the support. I have received through the peer review process and support the editorial office where they are to support young authors like me, encourage them to publish their work in your esteemed journals, and globalize and share knowledge globally. I really appreciate your journal, peer review, and editorial office.