AUCTORES

Globalize your Research

Research Article | DOI: https://doi.org/10.31579/2690-1919/240

* Department of Urology, North Manchester General Hospital, Delaunay’s Road, Crumpsall, Manchester, Lancashire, United Kingdom.

*Corresponding Author: Anthony Kodzo-Grey Venyo, Department of Urology, North Manchester General Hospital, Delaunay’s Road, Crumpsall, Manchester, Lancashire, M8 5RB, United Kingdom.

Citation: Anthony K. G Venyo, (2022). Cystitis Cystica and Cystitis Glandularis of the Urinary Bladder: A Review and Update. J Clinical Research and Reports, 11(1); DOI:10.31579/2690-1919/240

Copyright: © 2022. Anthony K. G. Venyo. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received: 02 March 2022 | Accepted: 21 March 2022 | Published: 31 March 2022

Keywords: cystitis cystica; cystitis glandularis; von Brunn nest; histopathology; immunohistochemistry; beta catenin; GATA 3; CK7; CK20; p63; uroplakin II/III; thrombomodulin; E-cadherin; CDX2; villin; MUC2; MUC5AC; trans-urethral resection; benign

Cystitis glandularis is a proliferative disorder of the urinary bladder which has tended to be associated with glandular metaplasia of the transitional cells that line the urinary bladder. Cystitis glandularis tends to be closely related to cystitis cystica with which it commonly does exist. Cystitis cystica represents a proliferative or reactive changes which tend to occur within von Brunn nests which do acquire luminal spaces and become cystically dilated, and cystitis may undergo glandular metaplasia which does represent cystitis glandularis or the cystitis may undergo intestinal type of metaplasia which is referred to as intestinal type of cystitis. Cystitis cystica and cystitis glandularis is a very common incidental finding. Cystitis cystica and glandularis tend to develop I the setting of chronic irritation or inflammation of the urinary bladder mucosa. Cystitis cystica and glandularis tend to be frequently found in co-existence with interrelated lesions and they represent benign simulators of invasive carcinoma of the urinary bladder. With regard to mode of manifestation and diagnosis, cystitis cystica and cystitis glandularis tend to be diagnosed incidentally based upon: findings of urinary bladder lesions at cystoscopy undertaken for some other reason or upon incidental finding of a urinary bladder lesion following the undertaking of radiology imaging (ultra-sound scan, or computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan undertaken for something else. The patient may also manifest with lower urinary tract symptoms of urinary frequency, urgency, urge incontinence or poor flow of urine or difficulty in initiating urine. On rare occasions when the ureteric orifices are involved the patient may manifest with one sided loin pain or bilateral loin pain if both ureteric orifices are obstructed by the urinary bladder lesion. In severe cases of bilateral ureteric obstruction there may be evidence of impairment of renal function. Haematuria could also be a mode of presentation. Ultrasound scan of renal tract could demonstrate a polypoidal thickening of the wall of the urinary bladder usually in the trigone of the bladder but in extensive cases the thickening could be all over the urinary bladder and in cases where the ureteric orifices are obstructed there may be evidence of hydroureter and hydronephrosis. CT scan may show hyper-vascular polypoid mass within the urinary bladder, and MRI scan could demonstrate a hyperintense vascular core with encompassing low-intensity signal. These radiology imaging features are non-specific and would differentiate the urinary bladder lesion from invasive urothelial carcinoma. Diagnosis of the cystitis tends to be made based upon histopathology examination and immunohistochemistry staining studies of biopsy specimens or the trans-urethral resection specimens of the urinary bladder lesions. Microscopy pathology examination of the specimens tend to demonstrate: (a) abundant urothelial von Brunn nests which often tend to exhibit a vaguely lobular distribution of invaginations as well evidence of non-infiltrative growth as well as growth and variable connection to surface, (b) Gland-like lumina with columnar or cuboidal cells with regard to cases of cystitis glandularis, (c) Cystically dilated lumina or cystic cavities which are filled with eosinophilic fluid in the scenario of cystitis cystica, (d) Majority of cases of cystitis tend to demonstrate coexistence of both patterns, (e) Cells lack significant atypia, mitotic activity, stromal reaction and muscular invasion and degenerative atypia tends to be occasionally present. Immunofluorescence studies in cases of cystitis glandularis tend to demonstrate uniform membranous expression of beta catenin without cytoplasmic or nuclear localization. Cases of cystitis cystica and cystitis glandularis tend to exhibit positive immunohistochemistry staining for various markers as follows: GATA3, CK7, (full thickness), CK20 (umbrella cells), p63 (basal cell layer), uroplakin II/III, thrombomodulin, beta catenin, (membranous), and E-cadherin. Cases of cystitis cystica and cystitis glandularis tend to exhibit negative immunohistochemistry staining for the following immunohistochemistry staining agents: CDX2, Villin, MUC2, MUC5AC, and beta catenin, (nuclear). Some of the differential diagnoses of cystitis cystica and cystitis glandularis include: von Brunn nest hyperplasia, Urothelial carcinoma in situ, Inverted Urothelial papilloma, Nested variant of invasive urothelial carcinoma, and Microcystic variant of urothelial carcinoma. On rare occasions cystitis cystica and cystitis glandularis could be found contemporaneously in association with a urothelial carcinoma and hence every pathologist who examines specimens of cystitis cystica and cystitis glandularis needs to undertake a thorough examination of various areas of the bladder lesion to be absolutely sure there is no synchronous malignancy in the urinary bladder lesion. The treatment of cystitis cystica does entail removal of the source of irritation or source of the bladder inflammation including foreign bodies, long-term urinary catheter, vesical calculus and others as well as trans-urethral resection of the urinary bladder lesion or lesions. On very rare occasions cystectomy had been undertaken. Individuals who have vesical-ureteric obstruction may require insertion of nephrostomy on the side of the obstruction followed by insertion of antegrade or retrograde ureteric stents due to scarring at the site of obstruction or when the scar is too dense then excision of the lesion and re-implantation of the ureter may be required. In cases of severe impairment of renal function, on very rare occasions dialysis may be required as supportive care. But for majority of patients, trans-urethral resection of the bladder lesion would tend to be enough.

It has been iterated that cystitis cystica is a terminology which is utilized for a hyperproliferative condition where initial submucosal masses of epithelial cells, termed ‘Brunns nests, do undergo cavitation to form fluid-filled cystic structures [1,2]. Cystitis cystica is conjectured to represent a local immune response to a chronic inflammatory stimulus and which has been stated to be associated with recurrent urinary tract infection [1]. It has been stated that when cystitis cystica is present in children, it very rarely does affect the male population. It has been documented that one study by Milošević et al. which had looked at patients who had confirmed cystitis cystica and no concurrent urinary tract abnormality over a 20-year period, of the 127 patients who had been identified [2]. It has been documented that cystitis glandularis does occur when there is metaplasia in a mucous secreting epithelium and it is typified by a central lining of cuboidal or columnar cells [1,3].

It has been stated that cystitis cystica has tended to be an uncommon clinical rare entity in children, and there had been only a handful of reported cases of cystitis cystica in children that had been reported in the literature [1]. In has been pointed out that one study which looked at all paediatric specimens that were taken from the urinary bladder over a 21-year period at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, only three patients were identified as having cystitis glandularis [1]. A clinical history for only one of these patients was available a retrospective study of [1], and it had remarked upon a previous bladder exstrophy repair [4]. A small number of individual cases had been published in children over the previous years [5-7].

It has been pointed out that an association had been documented with urinary bladder exstrophy, pelvic lipomatosis and recurrent urinary tract infections in a published article [1,7]. It has been iterated that both cystitis cystica and cystitis glandularis could manifest with irritative lower urinary tract symptoms as well as haematuria [1].

It has been pointed out that the significance of cystitis glandularis in relation to premalignant risk has been the subject of much debate [1]. It has been pointed out that at the moment, even though cystitis glandularis could be found to exist in contemporaneously in conjunction with carcinoma of the urinary bladder, sufficient evidence does not exist currently to confirm that the presence of cystitis glandularis does increase the potential for the future development malignant tumour in the bladder [1,8]. Nevertheless, it has been iterated that the premalignant risk with very widely proliferative cystitis glandularis lesions cannot completely be disregarded or excluded [1,7].

It has been pointed out that at the moment, the treatment of patients who have cystitis cystica does entail utilization of long-term antibiotic prophylaxis for urinary tract infections [2].

It has also been pointed out that for the treatment of cystitis glandularis, transurethral resection of the lesions has generally been the only treatment that has been required [1,7].

It has been explained that cystitis cystica et glandularis (CCEG) represents a benign, proliferative lesion of the urinary bladder mucosa which is typified the von Brunn’s nests growing into the lamina propria to become cystically dilated (CC) and metaplastically changing into goblet cells within the mucosa and submucosa of the urinary bladder epithelium (CG) [9,10].

It has been pointed out that all three conditions do commonly coexist and they could be identified within various settings, with the inclusion of normal urinary bladder mucosa, inflammatory diseases, as well as carcinoma [9,11].

It has been explained that the exact pathophysiology of CCEG is not well understood but it is most likely related to chronic irritation of the urinary bladder mucosa with activation of the humoral immune defence response [9,12]. and it has tended to be associated with recurrent urinary tract infections, chronic bladder outlet obstruction, [13] neurogenic bladder, bladder calculi, or catheterization [8,9].

Interestingly, it has also been documented that pelvic lipomatosis which is an uncommonly rare proliferative condition which causes increased deposition of fat around the urinary bladder, rectum and prostate has tended to be associated with CG, which had been found in up to 75% of patients with pelvic lipomatosis according to a reported article [9,14].

It has been documented that most patients who have CCEG had tended to be asymptomatic, and the lesions usually had tended to be seen incidentally during cystoscopy examination [9]. It has also been pointed out that with regard to symptomatic patients, haematuria, irritative lower urinary tract symptoms, and, rarely, upper urinary tract obstruction has been the commonest manifesting [9]. It has been pointed out that at cystoscopy, florid CCEG often tends to appear as submucosal nodules [8,9]. It has been pointed out that documented cases of CCEG which cause obstruction, albeit without causing irreversible renal injury, had been reported. Zhu et al. reported a patient who had CCEG which had caused unilateral ureteric obstruction and acute azotaemia (creatinine, 231 μmol/l) in whom no underlying cause for CCEG was identified. The patient had undergone resection of the 4 cm urinary bladder mass before the renal function returned to baseline levels [9,15].

Demirer et al. reported a case of CCEG which had caused bilateral ureterovesical junction obstruction which had resulted in presentation as renal colic, bilateral ureterohydronephrosis, and haematuria, which was managed by transurethral resection [16].

The association between CCEG and adenocarcinoma of the bladder, which was first reported in 1950, is stated to be controversial [9,17].

Yi et al. recently retrospectively evaluated 166 patients who had CG, and based upon their results concluded that isolated CG does not increase the risk for the development of carcinoma of the urinary bladder [9,18]. In view of this, follow up in the form of repeated cystoscopies had not been warranted. Nevertheless, it has been iterated that in the presence of dysplasia, long-term clinical follow up with cystoscopies would be required [19].

It has been pointed out that various options of definitive treatment options are available which do range from conservative management to aggressive management. It has also been explained that: the identification of the lesion, treating the lesion, and eliminating the underlying predisposing source of chronic bladder irritation is the most crucial aspect of management of this clinical entity [9]. It has additionally been pointed out that the treatment of this clinical entity does include: the eradication of urinary tract infections with appropriate antibiotic treatment, replacing chronic indwelling urethral catheters with clean intermittent catheterization, or treating urinary bladder calculi [9]. It has also been recommended that symptomatic patients who manifest with bladder outlet obstruction, recurrent haematuria, or obstruction of the ureteric orifices should be managed with transurethral resection of the lesions [9,20].

It has been pointed out that success with these conservative measures tends to be more appropriate for small, focal lesions [9,21].

It has been explained that with regard to patients who experience debilitating symptoms, more invasive and aggressive surgical options would need to be considered [9]. It has additionally been pointed out that patients who have decreased urinary bladder capacity might benefit from a bladder augmentation surgical procedure, and, with regard to patients who have persistent ureteric obstruction, reimplantation of the ureter would be indicated [9,21].

It has additionally been pointed out that radical cystectomy with an orthotopic neobladder represents the most aggressive yet successful surgery which had been undertaken in highly selected cases [9,22].

Although CCEG is regarded as a common benign self-limiting condition requiring minimal intervention in most cases, it may, very rarely, obstruct the upper urinary tracts [9].

Internet data bases were searched including: Google; Google Scholar; Yahoo; and PUBMED. The search words that were used included: Cystitis cystica of bladder; Cystitis cystica of urinary bladder; Cystitis glandularis of bladder; Cystitis glandularis of urinary bladder; Cystitis Cystica et Glandularis of bladder; and Cystitis Cystica et glandularis of the urinary bladder. Fifty (50) references were identified which were used to write the article which has been divided into two parts: (A): Overview and (B): Miscellaneous Narrations And Discussions From Some Case Reports On Cystitis Cystica.

[A} Overview

Definition / general statements

It has been iterated that proliferative or reactive changes which occur within von Brunn nests that acquire luminal spaces, tend to become cystically dilated and they are referred to as cystitis cystica, and when they do undergo glandular metaplasia, they are then referred to as cystitis glandularis, as well as when they undergo intestinal type metaplasia they are then referred to as cystitis glandularis of the intestinal type [23].

Essential features [23]

The following essential features of cystitis cystica and cystitis glandularis have been summated: [23]

Terminology

Clinicians have been reminded that various terminologies have been utilized for cystitis cystica and cystitis glandularis and these include: [23]

Epidemiology [23]

Sites

The sites for the development of cystitis cystica and cystitis glandularis of the urothelium have been summarized to include the following: [23]

Pathophysiology

Aetiology

The clinical features of cystitis cystica and cystitis glandularis have been summated as follows: [23]

Diagnosis

With regard to the diagnosis of cystitis cystica and cystitis glandularis, it has been iterated that the diagnosis does rely upon microscopic histopathology examination of resected specimen of the urothelial tissue of the lesion [23].

Radiology imaging features

Fluoroscopy

Ultrasound scan

Ultrasound scan in cases of cystitis cystica and cystitis glandularis would tend to demonstrate a focal polypoidal wall thickening of the urinary bladder within the area of the trigone but in extensive cases the lesions could be found all over the bladder but these are non-specific findings that are not diagnostic of the lesion.

Computed Tomography (CT) Scan

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) Scan.

Prognostic factors

Treatment

Some of the objectives for the treatment of cystitis glandularis include: [23]

Cystoscopy Gross description [23,26,28]

Microscopic (histologic) description [23]

Immunofluorescence description [23]

Positive immunohistochemistry stains

It has been pointed out that cystitis glandularis of urinary bladder specimens would tend to exhibit positive immunohistochemistry staining for the following immunohistochemistry staining agents: [23]

Negative Immunohistochemistry stains

It has been pointed out that cystitis glandularis of urinary bladder specimens would tend to exhibit negative immunohistochemistry staining for the following immunohistochemistry staining agents: [23]

Differential diagnosis

Some of the differential diagnoses of cystitis glandularis and cystitis cystica have been documented to include the ensuing immunohistochemistry staining agents: [23]

[B] Miscellaneous Narrations and Discussions From Some Case Reports On Cystitis Cystica

Bastianpillai et al. [1] reported a 16-year-old boy who did not have any past urological or medical history had presented to his general practitioner with a six-month history of strangury, poor flow of urine, suprapubic discomfort, urinary frequency and urgency. He had also experienced one recent episode of visible haematuria. He did not have any significant family medical history or congenital abnormality noted. The results of his blood tests demonstrated a normal renal function. He had ultrasound scan of his urinary tract which had been ordered in the community, and which had shown two large polypoidal masses that had arisen from the right and left lateral walls of his urinary bladder, that measured up to 2.1 cm and 2.5 cm, respectively. The remainder of his urinary tract was unremarkable, and he did not have any significant post-voiding residual urine volume (see figure 1).

Reproduced from: [1] Bastianpillai C, Warner R, Beltran L, Green J. Cystitis cystica and glandularis producing large bladder masses in a 16-year-old boy. JRSM Open. 2018 Mar 8; 9(3):2054270417746060. doi: 10.1177/2054270417746060. PMID: 29552345; PMCID: PMC5846953. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5846953/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29552345/

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2018 Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed as specified on the SAGE and Open Access pages (https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/open-access-at-sage).

The patient was next urgently referred to be seen by the urology team. Pursuant to further discussion within the clinic with the patient and his parents, a decision was made to proceed directly to undertake cystoscopy under general anesthesia for his further assessment and possible resection of these lesions. His urine specimen was sent for cytology examination which demonstrated a few inflammatory cells but no overtly malignant cells within the urine. He had serial urine cultures which did not demonstrate any growth and he had no history of previous urinary tract infections. During his cystoscopy examination, following dilatation of his tight urethral meatus from 14Ch, the two large polypoid lesions were visualized on either side of the neck of his urinary which were partially obstructing, and which simulated malignancy in some areas and inflammatory masses in other areas (see figure 2). The remainder of the urethra was found to be normal. None of the two ureteric orifices was visualised. Both of his urinary bladder lesions were resected using a 17Ch resectoscope, and a small red area upon the posterior wall of his urinary bladder was biopsied. A decision was made to resect most of the lesions from around his urinary bladder neck, leaving as much normal or non-polypoid tissue as possible to reduce the risk of bladder neck stenosis. The patient was kept overnight for irrigation of his urinary bladder, and the catheter was removed the following day with no postoperative complications.

Reproduced from: [1] Bastianpillai C, Warner R, Beltran L, Green J. Cystitis cystica and glandularis producing large bladder masses in a 16-year-old boy. JRSM Open. 2018 Mar 8;9(3):2054270417746060. doi: 10.1177/2054270417746060. PMID: 29552345; PMCID: PMC5846953. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5846953/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29552345/

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2018. Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed as specified on the SAGE and Open Access pages (https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/open-access-at-sage).

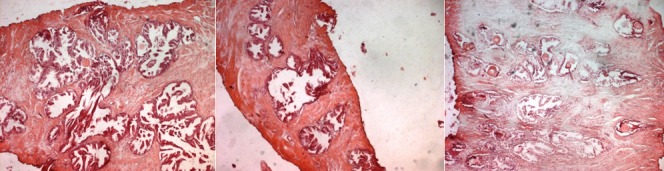

Histopathology examination of the resected tissue demonstrated features of florid cystitis cystica and cystitis glandularis in all three specimens. Muscle was included in two of the three specimens. No intestinal metaplasia was visualized, and no evidence of dysplasia or malignancy was evident (see figure 3). The patient subsequently had a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of his pelvis which did not demonstrate any other abnormalities within the pelvis (see figure 4). His lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) had subsided one month pursuant to his surgery and his urine flow rate had returned to normal. Pursuant to a multi-disciplinary team meeting discussion, a recommendation was made to repeat cystoscopy on the patient in six months.

Reproduced from: [1] Bastianpillai C, Warner R, Beltran L, Green J. Cystitis cystica and glandularis producing large bladder masses in a 16-year-old boy. JRSM Open. 2018 Mar 8;9(3):2054270417746060. doi: 10.1177/2054270417746060. PMID: 29552345; PMCID: PMC5846953. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5846953/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29552345/

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2018. Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed as specified on the SAGE and Open Access pages (https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/open-access-at-sage).

Reproduced from: [1] Bastianpillai C, Warner R, Beltran L, Green J. Cystitis cystica and glandularis producing large bladder masses in a 16-year-old boy. JRSM Open. 2018 Mar 8;9(3):2054270417746060. doi: 10.1177/2054270417746060. PMID: 29552345; PMCID: PMC5846953. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5846953/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29552345/

Copyright © The Author(s) 2018. Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed as specified on the SAGE and Open Access pages (https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/open-access-at-sage).

Takizawa et al. [33] made the ensuing iterations related to cystitis glandularis:

Takizawa et al. [33] experienced a case of remission from cystitis glandularis after combination treatment which included: oral treatment with selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, celecoxib and transurethral resection. Immunohistochemistry staining studies of the bladder lesion showed positive signals of cyclooxygenase-2 in the epithelium of pre-treatment specimens, which had suggested the pathophysiological role of cyclooxygenase-2 in cystitis glandularis. Takizawa et al. [33] did demonstrate the effectiveness of celecoxib against cystitis glandularis for the first time. Takizawa et al. [33] iterated that Celecoxib could be one of the treatment strategies for cystitis glandularis.

Potts and Calleary [34] in 2017, described the rare and not previously documented presentation of cystitis cystica as a large solitary cystic lesion within the wall of a urinary bladder. The patient was a 46-year-old Russian male who had manifested with a history of lower urinary tract symptoms and suprapubic pain. He had a contrast computed tomography (CT) Urogram which demonstrated a 5.8 cm filling defect/cystic mass that was related to the base of his urinary bladder and prostate gland with 8 mm thick wall. He underwent cystoscopy and contrast study of bladder lesion with urethral dilatation and transurethral deroofing of the urinary bladder wall cyst under general anaesthesia. A histology diagnosis of cystitis cystica was made. Potts and Calleary [34] made the following conclusions:

Smith et al. [35] stated the following:

Smith et al. [35] retrospectively evaluated the association among florid CCEG, IM, and carcinoma of the urinary bladder. They reviewed the clinical records and radiology imaging findings of patients who had a pathology diagnosis of florid CCEG and/or IM for a concurrent or future diagnosis of bladder carcinoma or pelvic lipomatosis. Smith et al. [35] summarized the results as follows:

Smith et al. [35] made the ensuing conclusions:

Zhu et al. [36] reported a 43-year-old man who had manifested to the emergency room (ER) with a 3-day history of intermittent left flank pain which had lasted several hours at a time that was associated with nausea. He was afebrile and hypertensive with a blood pressure of 173/82 mmHg. He did not have any previous history of visible, kidney stones, trauma or chronic/recurrent urinary tract infections. He was otherwise healthy with a known umbilical and left inguinal hernia, both of which were noted to be reducible upon examination. His initial assessment demonstrated a completely normal examination with no evidence of costovertebral angle tenderness. Social history revealed that he was a body builder who took creatine supplements daily and smoked 2 to 3 cigarettes per day for the past 5 years.

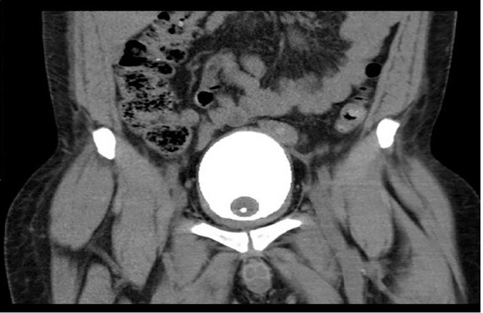

An urgent ultrasound of his renal tract demonstrated a bladder mass within the trigone (see figure 1a with left hydronephrosis, with left hydroureter and left hydronephrosis. The left ureteric jet could not be demonstrated upon the ultrasound scanning. He then next had a non-contrast computed tomography scan of the abdomen and pelvis which did noy reveal any renal or ureteric calculi to account for the hydroureter. Urinalysis was undertaken which was negative for nitrites or leukocytes; His urine upon cytology examination later came back negative for malignancy. The results of his routine haematology and biochemistry serum blood test results were within was normal range with the exception of a high creatinine of 231 μmol/L (baseline 109 μmol/L in 2005) with a blood urea nitrogen (BUN)/Cr ratio of 37.7, which had indicated acute azotemia. Considering that his pain had resolved and that his serum creatinine had reduced to 206 μmol/L after he had had fluid resuscitation, he was discharged home with the plan for him to undergo an urgent urology follow-up. Three days subsequently, the patient re-presented to the Emergency Room (ER) with ongoing flank pain and for which he was taken to the operating theatre to undergo trans-urethral resection of the bladder tumour (TURBT). His cystoscopy examination demonstrated a large mass which had arisen from his bladder neck, and which had extended along the base of the urinary bladder and which had covered his left ureteric orifice such that the ureteric orifice could not be visualised. The right ureteric orifice was found to be lateral and golf-hole in appearance. The tumour measured over 4 cm in size and it did not exhibit the characteristic appearance of papillary urothelial carcinoma and it did appear to be more solid in nature. The mass was resected completely, down to the base and the area of the resected lesion was fulgurated. The results of his serum creatinine quickly stabilized at 106 μmol/L and he was discharged home in a stable condition, which had suggested that his ureterovesical junction (UVJ) obstruction was the primary reason behind his acute azotemia upon presentation. It was still not clear why the patient went into acute renal failure with obstruction of one renal unit. His hospital chart was reviewed but it did not reveal the use of nephrotoxic medications. The authors conjectured that it was possible; nevertheless, that the sheer mass effect of the lesion, which had traversed the entire base of his urinary bladder, might have also led to a functional obstruction of the contralateral ureteric drainage.

Transurethral resection of the urinary bladder lesion was undertaken to obtain a definitive diagnosis. Pathology examination of the resected urinary bladder lesion demonstrated a 5.1 grams of bladder tissue which depicted an intact urothelial epithelium with underlying oedematous lamina propria. Florid cystitis cystica et glandularis (CCEG), common type, was identified within the lamina propria. The lesion had comprised of many glands that were lined by columnar or cuboidal cells and which were encompassed focally by urothelial cells. There was no evidence of cytological atypia within the lining of the glands found upon histopathology examination of the specimen noted. There was no evidence of intestinal metaplasia or mucin production. Additionally, there was no evidence of dysplasia, carcinoma in situ or papillary urothelial carcinoma.

With regard to the management of the patient, the results of the first biopsy were discussed with the patient, a 3-month post-TURBT cystoscopy examination was undertaken which demonstrated a recurrence of the mass, although to a lesser extent, within the same region of the urinary bladder. The microscopy pathology examination of the bladder tissue of the recurrent lesion did demonstrate morphology features in comparison to the first biopsy. His serum creatinine had once again risen to 132 μmol/L, so he underwent a repeat TURBT was and which demonstrated similar findings as the first operation. The authors, made the ensuing summating iterations:

It would be argued that the important messages that should be learnt from this case narration include:

Bhana et al. [9] reported a 32-year-old human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-negative man who was referred to their unit with a 2-week history of bilateral flank pain and nausea. He was upon radiology imaging and laboratory blood testing to have gross bilateral hydroureter and hydronephrosis and a blood serum urea level of 87.5 mmol/l, creatinine 1840 μmol/l and an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 3 ml/min/1.73 m2. He did not have any significant post micturition residual urinary bladder volume that would suggest a bladder outlet obstruction on ultrasound scanning. The history was additionally considered to be unremarkable, with no preceding history of haematuria, lower urinary tract symptoms, surgical procedures, urolithiasis, or previous urinary tract infections. His clinical examination demonstrated him to be afebrile and normotensive with mild bilateral loin tenderness. Examination of specimens of his urine for urinalysis and culture demonstrated no evidence of urinary tract infection, tuberculosis or schistosomiasis.

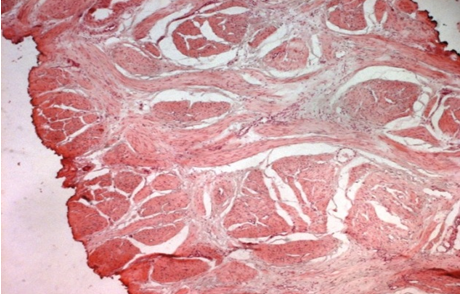

Urgent haemodialysis was started, and he underwent cystoscopy which demonstrated extensive cystic and nodular lesions which had involved most of his urinary bladder urothelium, but this was especially prominent at the trigone and bladder neck regions. His ureteric orifices could not be visualized, and retrograde stenting proved to be impossible. Pathology examination of biopsies of his abnormal urinary bladder urothelium demonstrated multiple foci of CCEG (see figure 5) and no evidence of dysplasia, malignancy, tuberculosis, or schistosomiasis was found.

Reproduced from: [9] Bhana K, Lazarus J, Kesner K, John J. Florid cystitis cystica et glandularis causing irreversible renal injury. Ther Adv Urol. 2021 Jun 10; 13:17562872211022465. doi: 10.1177/17562872211022465. PMID: 34178117; PMCID: PMC8202316. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34178117/https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8202316/

Copyright © The Author(s), 2021. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed as specified on the SAGE and Open Access page (https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/open-access-at-sage

Bilateral percutaneous nephrostomies were then inserted, and bilateral anterograde pyelography demonstrated distended ureters with complete obstruction at the level of both vesicoureteral junctions (see figure 6). No filling defects were found that would have been suggestive of concomitant ureteritis cystica were identified. At that stage, the management plan of the authors was to continue with dialysis of the with the bilateral percutaneous nephrostomies in situ and to allow time for the CCEG, which had generally been regarded as a self-limiting disease, to resolve. He had computed tomography (CT) cystogram which demonstrated a good capacity of his urinary bladder, with no evidence of pelvic lipomatosis (see figure 6).

Reproduced from: [9] Bhana K, Lazarus J, Kesner K, John J. Florid cystitis cystica et glandularis causing irreversible renal injury. Ther Adv Urol. 2021 Jun 10; 13:17562872211022465. doi: 10.1177/17562872211022465. PMID: 34178117; PMCID: PMC8202316. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34178117/ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8202316/

Copyright © The Author(s), 2021 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed as specified on the SAGE and Open Access page (https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/open-access-at-sage

Reproduced from: [9] Bhana K, Lazarus J, Kesner K, John J. Florid cystitis cystica et glandularis causing irreversible renal injury. Ther Adv Urol. 2021 Jun 10; 13:17562872211022465. doi: 10.1177/17562872211022465. PMID: 34178117; PMCID: PMC8202316. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34178117/ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8202316/

Copyright © The Author(s), 2021. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed as specified on the SAGE and Open Access page (https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/open-access-at-sage

He had repeat cystoscopy 6 weeks subsequently which demonstrated a marked improvement, with the urinary bladder lesions now limited only to the bladder neck and trigone. Careful resection of the remaining lesions on the trigone was undertaken which exposed slit-like ureteric orifices (see figure 8), but unfortunately, the two identified ureteric orifices could not be catheterised. He had repeat anterograde pyelography which did not show any resolution of the complete obstruction at the lower extent of both ureters.

Reproduced from: [9] Bhana K, Lazarus J, Kesner K, John J. Florid cystitis cystica et glandularis causing irreversible renal injury. Ther Adv Urol. 2021 Jun 10; 13:17562872211022465. doi: 10.1177/17562872211022465. PMID: 34178117; PMCID: PMC8202316. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34178117/ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8202316/ Copyright © The Author(s), 2021

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed as specified on the SAGE and Open Access page (https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/open-access-at-sage

The patient’s serum renal function did not demonstrate any improvement despite the decompressing effect of the bilateral percutaneous nephrostomies. The authors iterated that after they had observed that follow-up cystoscopy had demonstrated resolution of the macroscopic cystic and nodular lesions within the urinary bladder and no lesions were found that would require re-resection, a multidisciplinary decision was made to continue haemodialysis and to place the patient on a waiting list for a renal transplant.

Bhana et al. [9] made the following conclusions:

A lesson that needs to be learnt from this case report is that CCEG could be associated with bilateral ureteric obstruction and severe renal failure that could require haemodialysis and renal transplantation.

Yi et al. [37] iterated the following:

Yi et al. [37] retrospectively evaluated the association between intestinal and typical CG and carcinoma of the urinary bladder carcinoma. The patients that were included in their study had manifested with typical CG in 155 cases or intestinal CCG in11 cases between 1994 and 2010. Out of those patients, concurrent carcinoma of the urinary bladder was identified in 15 patients that amounted to 9.0% of the patients, including two cases of squamous cell carcinoma and 1 case of sarcoma of the urinary bladder. The cases of carcinoma were identified either preceding or contemporaneously with the diagnosis of CG. Follow‑up was available for 9 out of /11 patients that amounted to 81.8% of the patients who had intestinal CG. Nine months following transurethral fulguration, 8 out of 11 patients that amounted to 72.7% of the patients were in complete remission and 1 patient out of the 11 patients that amounted to 9.1% of the patients had manifested with urinary urgency and dysuria; two patients were lost to follow‑up. The follow‑up of the patients had ranged from 0.7 years to 4.5 years and their median follow-up was 2.67 years; and their mean follow-up was 2.82 years. During the follow-up of the patients no evidence of subsequent development of carcinoma was identified in any of the patients during the follow‑up of both the intestinal and typical CG groups of patients. Additionally, there was no evidence of carcinoma subsequent to CG in either of the typical or intestinal CG groups of patients.

Yi et al. [37] iterated that the results did not support the suggestion that CG does increase the future risk of the development of malignancy in the short term and that they would not recommend repeated cystoscopies over a short period of time.

Velickovic et al. [38] stated that a wide spectrum of glandular epithelial metaplastic changes could be visualised in the bladder and that cystitis glandularis (CG) is a well-known metaplastic lesion which does tend to occur in the presence of chronic inflammation; nevertheless, there are a few data about mucin expression in its two subtypes (typical and intestinal). The purpose of the study of Velickovic et al. [38] was to determine the expression of mucin core proteins and CD10 in the different types of CG. For this examination, they utilized a panel of monoclonal-specific antibodies for MUC1, MUC2, MUC5AC, and MUC6. CG of the intestinal type expressed MUC5AC both in goblet and columnar cells, and strongly expressed intestinal mucin MUC2 only in goblet cells in all cases. Velickovic et al. [38] reported that there was no immunohistochemistry expression of MUC1, MUC6, and CD10 in the metaplastic cells. CG of the typical type exhibited an expression of MUC1 that was similar to normal urothelium; however, the CD10 immunohistochemistry expression was more intensive than in the control group. Velickovic et al. [38] iterated the following:

Lee et al. [39] reported a rare case of a 26-year-old patient who had presented with a 3-week history of visible haematuria and suprapubic discomfort. The patients’ investigations demonstrated a tumour which had arisen from the wall of the urinary bladder and histopathology examination of the specimen demonstrated features that were consistent with the diagnosis of cystitis glandularis. Their literature review had highlighted the rarity of cystitis glandularis presented in such manner. They suggested that radiographic and endoscopic images could also assist in the future diagnosis of the condition especially in patients in their reported age groups.

Kaya et al. [40] stated that cystitis glandularis is a very rare proliferative disorder of the mucus-producing glands within the mucosa and submucosa of urinary bladder epithelium. Kaya et al reported such a case of glandular cystitis with intestinal metaplasia masquerading as a urinary bladder tumour in a young male patient who has manifested with severe obstructive urinary symptoms. The patient underwent cystoscopy which demonstrated a well circumscribed, mass that measured 5 ×4 m on the trigone. Transurethral resection of the mass was undertaken and histopathology examination of the resected lesion demonstrated features that were consistent with suggested cystitis glandularis. The literature regarding this entity was been reviewed and the differential diagnosis was discussed. Short-term follow-up of the patient with sonography and cystoscopy showed no recurrence. Kaya et al. [40] made the ensuing summary related to cystitis glanduris:

Kaya et al. [40] concluded that TPRG1 had promoted inflammation and cell proliferation of cystitis glandularis via the activation of NF-кB/COX2/PGE2 axis.

Hong et al. [41] made the ensuing iterations:

With regard to the method of their study, Hong et al. [41] reported the following: Firstly, they had isolated urinary bladder specimens from patients who had cystitis glandularis and E. coli-induced cystitis rat. With regard to the results, Hong et al. [41] reported the following:

Hong et al. [41] concluded that TPRG1 had promoted inflammation and cell proliferation of cystitis glandularis via activation of NF-кB/COX2/PGE2 axis.

Qu et al. [42] investigated the relationships of urinary bladder mucosal inflammatory factors, interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) with the occurrence and development of cystitis glandularis (CG), and their effects upon the prognosis of patients. With regard to the methods, Qu et al. [42] reported that a total of 61 patients who had CG from January 2010 to 2014 were randomly selected and tissue specimens of postoperative patients were collected. 16 cases of normal urinary bladder mucosa during the same period were obtained as a control group. Blood specimens and fresh tissue specimens had been collected from 6 patients who had CG. The messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) levels of IL-1, IL-6 and TNF-α were detected by means of a reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). The protein levels of IL-1, IL-6 and TNF-α in serum of patients who had GC and normal controls were detected through an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The protein expressions of IL-1, IL-6 and TNF-α were ascertained via immunohistochemistry (IHC), and their relationships with the clinical features and prognosis of GC were analysed. A Cox proportional hazard regression model was utilised for multivariate analysis on the prognostic factors of CG, and all the tests were undertaken with 95% confidence interval (CI). Qu et al. [42] summarised the results as follows:

Qu et al. [42] made the following conclusions:

Qiu et al. [43] evaluated the safety and efficacy of trans-urethral front-firing photo-selective vaporesection for the treatment of cystitis glandularis, by comparing the procedure with the trans-urethral bipolar plasmakinetic resection. With regard to the methods of the study, Qiu et al. [43] reported that from January 2014 to July 2016, 41 patients who had pathology examination diagnosed cystitis glandularis in their hospital, were divided into two groups which included the following: Twenty two (22) cases had undergone trans-urethral front-firing photoselective vaporesection which constituted the observation group, and the other 19 cases had undergone transurethral bipolar plasmakinetic resection which represented the control group of patients. All of the patients were regularly treated with postoperative intra-vesical instillation chemotherapy with utilization of pirarubicin. The clinical data of two groups were statistically analysed in order to compare the differences of the safety and efficacy of the treatment options. Qiu et al. [43] summarized the results as follows:

Qiu et al. [43] concluded that comparing the traditional trans-urethral bipolar plasma kinetic resection for the treatment of cystitis glandularis, trans-urethral front firing photo-selective vaporesection with postoperative intravesical instillation chemotherapy with pirarubicin, was found to be a safer, simpler, and more effective method, which could be a new optional method of treatment of cystitis glandularis within the conditional hospitals, deserving the worthy of clinical popularization.

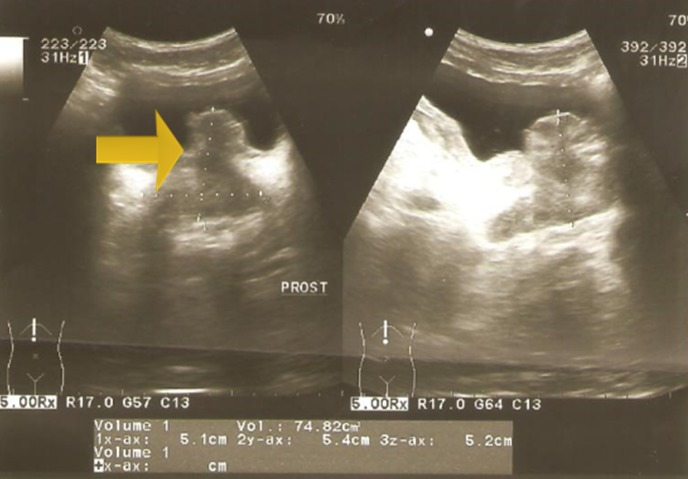

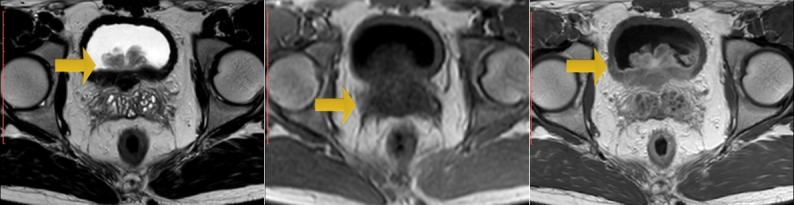

Zouari et al. [44] reported a 22-year-old man, who did not have any past medical history, who had consulted in emergency for acute urinary retention and left renal colic. Bladder catheterization was undertaken as well as an ultrasound scan which showed left obstructive pre-meatus calculi of 6 mm and distension of his urinary bladder. Upon examination the patient was found to be afebrile and a slight tenderness on the left flank was found upon his abdominal palpation. Upon digital examination (DRE), Zouari et al. [44] found an enlarged prostate gland; there were no indurations and no areas of softness or tenderness within the prostate gland found during the examination. An anti-inflammatory and antalgic treatment was provided to the patient. After one week, Zouari et al. [44] removed the urethral catheter but the patient was still having dysuria. Another ultrasound scan was undertaken; there was an inflammatory aspect of the bladder noted with a thickened bladder wall and a tissular proliferation that measured 5*2 cm on the bladder neck and at the left wall with large implantation and probably prostate infiltration. It was vascularized on color Doppler ultrasound scan (see figure 9, and figure 10). Meanwhile, the patient had developed another episode of acute urinary retention few weeks subsequently. His biological examinations were normal. Urine His Urinalysis was normal. His serum prostate specific antigen (PSA) level was about 1.6 ng/ml. He had magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan which demonstrated a pseudo-tumoral urinary bladder wall thickening which was associated with vesical floor budding with prostate median lobe infiltration (see figure 11 and figure 12). The patient was admitted for an endoscopic examination which was undertaken on March, 9th, 2016 and the examination demonstrated an inflammatory aspect of the bladder mucosa as well as a solid mass within the neck of the urinary which had arisen from the prostate gland most likely. It was difficult to determine the origin of the mass, whether it was from the prostate gland or from the urinary bladder. Cystoscopy was undertaken and a biopsy of the presumed mass was taken for pathology examination. Pathology examination of the mass that was biopsied during the cystoscopy revealed features that were considered as conclusively diagnosing a glandular cystitis without any features of malignancy (see figure 13). During the follow up assessment of the patient, he still had dysuria as well as urinary incontinence/leakage. He had ultrasound scan six months later which demonstrated an enlarged prostate gland of 60grams volume, and his post void residual volume of urinary bladder urine was 280ml and he was also found to have bilateral hydronephrosis. The patient was admitted to hospital again in March 2017 and a second cystoscopy was undertaken. The cystoscopy examination revealed that the prostate gland was obstructive with a median lobe. A trans urethral resection of the median lobe of the prostate gland was undertaken. Pathology examination of the resected median lobe of the prostate confirmed features of a benign prostate hyperplasia (see figure 14 and 15).

Reproduced from: [44] Zouari S, Bouassida K, Ahmed KB, Thabet AB, Krichene MA, Jebali C. Acute urinary retention due to benign prostatic hyperplasia associated with cystitis glandularis in a 22-year-old patient. Pan African. Medical Journal. 2018 May 16; 30:30. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2018.30.30.14835. PMID: 30167057; PMCID: PMC6110568. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6110568/

Copyright © Skander Zouari et al. The Pan African Medical Journal - ISSN 1937-8688. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reproduced from: [44] Zouari S, Bouassida K, Ahmed KB, Thabet AB, Krichene MA, Jebali C. Acute urinary retention due to benign prostatic hyperplasia associated with cystitis glandularis in a 22-year-old patient. Pan African Medical Journal. 2018 May 16; 30:30. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2018.30.30.14835. PMID: 30167057; PMCID: PMC6110568. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6110568/ Copyright © Skander Zouari et al. The Pan African Medical Journal - ISSN 1937-8688. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reproduced from: [44] Zouari S, Bouassida K, Ahmed KB, Thabet AB, Krichene MA, Jebali C. Acute urinary retention due to benign prostatic hyperplasia associated with cystitis glandularis in a 22-year-old patient. Pan African. Medical Journal. 2018 May 16; 30:30. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2018.30.30.14835. PMID: 30167057; PMCID: PMC6110568. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6110568/ Copyright © Skander Zouari et al.The Pan African Medical Journal - ISSN 1937-8688. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reproduced from: [44] Zouari S, Bouassida K, Ahmed KB, Thabet AB, Krichene MA, Jebali C. Acute urinary retention due to benign prostatic hyperplasia associated with cystitis glandularis in a 22-year-old patient. Pan African. Medical Journal. 2018 May 16; 30:30. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2018.30.30.14835. PMID: 30167057; PMCID: PMC6110568. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6110568/ Copyright © Skander Zouari et al.

The Pan African Medical Journal - ISSN 1937-8688. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reproduced from: [44] Zouari S, Bouassida K, Ahmed KB, Thabet AB, Krichene MA, Jebali C. Acute urinary retention due to benign prostatic hyperplasia associated with cystitis glandularis in a 22-year-old patient. Pan African. Medical Journal. 2018 May 16; 30:30. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2018.30.30.14835. PMID: 30167057; PMCID: PMC6110568. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6110568/ Copyright © Skander Zouari et al. The Pan African Medical Journal - ISSN 1937-8688. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reproduced from: [44] Zouari S, Bouassida K, Ahmed KB, Thabet AB, Krichene MA, Jebali C. Acute urinary retention due to benign prostatic hyperplasia associated with cystitis glandularis in a 22-year-old patient. Pan African. Medical Journal. 2018 May 16; 30:30. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2018.30.30.14835. PMID: 30167057; PMCID: PMC6110568. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6110568/ Copyright © Skander Zouari et al. The Pan African Medical Journal - ISSN 1937-8688. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reproduced from: [44] Zouari S, Bouassida K, Ahmed KB, Thabet AB, Krichene MA, Jebali C. Acute urinary retention due to benign prostatic hyperplasia associated with cystitis glandularis in a 22-year-old patient. Pan African. Medical Journal. 2018 May 16; 30:30. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2018.30.30.14835. PMID: 30167057; PMCID: PMC6110568. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6110568/ Copyright © Skander Zouari et al. The Pan African Medical Journal - ISSN 1937-8688. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Mo et al. [45] made the following iterations:

Mo et al. [45] reported a patient who was suffering from PL with CG and who was treated by means of transurethral resection of bladder tumour (TUR-BT) and oral administration of celecoxib, a selective cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitor. The LUTS of the patient were alleviated, and the cystoscopy results improved significantly. Immunohistochemistry staining studies of the resected urinary bladder mass demonstrated up-regulated COX-2 expression in the epithelium of the TUR-BT samples, which had suggested that COX-2 might participate in the pathophysiological process of PL combined with CG.

Mo et al. [45] concluded that they had reported for the first time that celecoxib might be an effective treatment strategy for PL combined with refractory CG.

Zhou et al. [46] stated the following:

In their study, Zhou et al. [46] firstly isolated the primary cells from the tissues of CG and adjacent normal tissues, and they found that UCA1 was up-regulated in the primary CG cells (pCGs). Then, Zhou et al. [46] demonstrated that knock out of UCA1 had reduced the cell viability, had inhibited the cell proliferation and had restrained the migration potential and overexpression of UCA1 promoted that in pCGs. Additionally, Zhou et al. [45 new 46] had demonstrated that UCA1 had played its role through sponging of the miR-204 in pCGs. Furthermore, Zhou et al. [46] illustrated that miR-204 exerted its function through targeting CYCLIN D2 (CCND2) 3′UTR at mRNA level in pCGs. Ultimately, Zhou et al. [46] revealed the role and regulation of UCA1/miR-204/CCND2 regulatory axis in pCGs. In summary, Zhou et al. [46] stated that their study, for the first time, had illustrated the role and underlying mechanism of an- lncRNA UCA1 in CG, providing a potential biomarker and therapeutic target for human CG.

Hu et al. [47] stated that majority of patients who have cystitis glandularis (CG) do suffer from recurrence after treatment of the primary lesion. Hu et al. [47] undertook a multi-centre study to clarify the recurrent risk factors and constructed a predictive nomogram for the risk of recurrence. Also, Hu et al. [47] tried to investigate the correlation between CG and bladder cancer. With regard to the methods of the study, Hu et al. [47] reported the following:

Hu et al. [47] summarized the results as follows:

Hu et al. [47] made the following conclusions:

Li et al. [48] stated the following:

With regard to the methods of their study, Li et al. [48] reported that they had compared the expression of messenger RNA (mRNA) and long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) from normal bladder mucosa and CG using microarray analysis. They utilized the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis to describe molecular interactions. Li et al. [48] summarised the results as follows:

Li et al. [48] conclude their study was the first work to measure the expression of dysregulated lncRNA and ceRNA in CG and identify the crosstalk between mRNA and lncRNA expression patterns in the pathogenesis of CG.

Garg et al. [49] studied the manifestation and natural course of cystitis cystica et glandularis. Garg et al. [49] undertook a retrospective analysis of patients who had histopathology examination confirmed cystitis cystica et glandularis from March 2016 to March 2018 who at least HAD completed their 2 years’ follow-up assessments. They included in the analysis the perioperative details along with the last available follow-up records. Garg et al. [48 new 49] summarized the results as follows:

Garg et al. [49] made the following conclusions:

Hong et al. [50] stated the following:

None.

Clearly Auctoresonline and particularly Psychology and Mental Health Care Journal is dedicated to improving health care services for individuals and populations. The editorial boards' ability to efficiently recognize and share the global importance of health literacy with a variety of stakeholders. Auctoresonline publishing platform can be used to facilitate of optimal client-based services and should be added to health care professionals' repertoire of evidence-based health care resources.

Journal of Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Intervention The submission and review process was adequate. However I think that the publication total value should have been enlightened in early fases. Thank you for all.

Journal of Women Health Care and Issues By the present mail, I want to say thank to you and tour colleagues for facilitating my published article. Specially thank you for the peer review process, support from the editorial office. I appreciate positively the quality of your journal.

Journal of Clinical Research and Reports I would be very delighted to submit my testimonial regarding the reviewer board and the editorial office. The reviewer board were accurate and helpful regarding any modifications for my manuscript. And the editorial office were very helpful and supportive in contacting and monitoring with any update and offering help. It was my pleasure to contribute with your promising Journal and I am looking forward for more collaboration.

We would like to thank the Journal of Thoracic Disease and Cardiothoracic Surgery because of the services they provided us for our articles. The peer-review process was done in a very excellent time manner, and the opinions of the reviewers helped us to improve our manuscript further. The editorial office had an outstanding correspondence with us and guided us in many ways. During a hard time of the pandemic that is affecting every one of us tremendously, the editorial office helped us make everything easier for publishing scientific work. Hope for a more scientific relationship with your Journal.

The peer-review process which consisted high quality queries on the paper. I did answer six reviewers’ questions and comments before the paper was accepted. The support from the editorial office is excellent.

Journal of Neuroscience and Neurological Surgery. I had the experience of publishing a research article recently. The whole process was simple from submission to publication. The reviewers made specific and valuable recommendations and corrections that improved the quality of my publication. I strongly recommend this Journal.

Dr. Katarzyna Byczkowska My testimonial covering: "The peer review process is quick and effective. The support from the editorial office is very professional and friendly. Quality of the Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions is scientific and publishes ground-breaking research on cardiology that is useful for other professionals in the field.

Thank you most sincerely, with regard to the support you have given in relation to the reviewing process and the processing of my article entitled "Large Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of The Prostate Gland: A Review and Update" for publication in your esteemed Journal, Journal of Cancer Research and Cellular Therapeutics". The editorial team has been very supportive.

Testimony of Journal of Clinical Otorhinolaryngology: work with your Reviews has been a educational and constructive experience. The editorial office were very helpful and supportive. It was a pleasure to contribute to your Journal.

Dr. Bernard Terkimbi Utoo, I am happy to publish my scientific work in Journal of Women Health Care and Issues (JWHCI). The manuscript submission was seamless and peer review process was top notch. I was amazed that 4 reviewers worked on the manuscript which made it a highly technical, standard and excellent quality paper. I appreciate the format and consideration for the APC as well as the speed of publication. It is my pleasure to continue with this scientific relationship with the esteem JWHCI.

This is an acknowledgment for peer reviewers, editorial board of Journal of Clinical Research and Reports. They show a lot of consideration for us as publishers for our research article “Evaluation of the different factors associated with side effects of COVID-19 vaccination on medical students, Mutah university, Al-Karak, Jordan”, in a very professional and easy way. This journal is one of outstanding medical journal.

Dear Hao Jiang, to Journal of Nutrition and Food Processing We greatly appreciate the efficient, professional and rapid processing of our paper by your team. If there is anything else we should do, please do not hesitate to let us know. On behalf of my co-authors, we would like to express our great appreciation to editor and reviewers.

As an author who has recently published in the journal "Brain and Neurological Disorders". I am delighted to provide a testimonial on the peer review process, editorial office support, and the overall quality of the journal. The peer review process at Brain and Neurological Disorders is rigorous and meticulous, ensuring that only high-quality, evidence-based research is published. The reviewers are experts in their fields, and their comments and suggestions were constructive and helped improve the quality of my manuscript. The review process was timely and efficient, with clear communication from the editorial office at each stage. The support from the editorial office was exceptional throughout the entire process. The editorial staff was responsive, professional, and always willing to help. They provided valuable guidance on formatting, structure, and ethical considerations, making the submission process seamless. Moreover, they kept me informed about the status of my manuscript and provided timely updates, which made the process less stressful. The journal Brain and Neurological Disorders is of the highest quality, with a strong focus on publishing cutting-edge research in the field of neurology. The articles published in this journal are well-researched, rigorously peer-reviewed, and written by experts in the field. The journal maintains high standards, ensuring that readers are provided with the most up-to-date and reliable information on brain and neurological disorders. In conclusion, I had a wonderful experience publishing in Brain and Neurological Disorders. The peer review process was thorough, the editorial office provided exceptional support, and the journal's quality is second to none. I would highly recommend this journal to any researcher working in the field of neurology and brain disorders.

Dear Agrippa Hilda, Journal of Neuroscience and Neurological Surgery, Editorial Coordinator, I trust this message finds you well. I want to extend my appreciation for considering my article for publication in your esteemed journal. I am pleased to provide a testimonial regarding the peer review process and the support received from your editorial office. The peer review process for my paper was carried out in a highly professional and thorough manner. The feedback and comments provided by the authors were constructive and very useful in improving the quality of the manuscript. This rigorous assessment process undoubtedly contributes to the high standards maintained by your journal.

International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews. I strongly recommend to consider submitting your work to this high-quality journal. The support and availability of the Editorial staff is outstanding and the review process was both efficient and rigorous.

Thank you very much for publishing my Research Article titled “Comparing Treatment Outcome Of Allergic Rhinitis Patients After Using Fluticasone Nasal Spray And Nasal Douching" in the Journal of Clinical Otorhinolaryngology. As Medical Professionals we are immensely benefited from study of various informative Articles and Papers published in this high quality Journal. I look forward to enriching my knowledge by regular study of the Journal and contribute my future work in the field of ENT through the Journal for use by the medical fraternity. The support from the Editorial office was excellent and very prompt. I also welcome the comments received from the readers of my Research Article.

Dear Erica Kelsey, Editorial Coordinator of Cancer Research and Cellular Therapeutics Our team is very satisfied with the processing of our paper by your journal. That was fast, efficient, rigorous, but without unnecessary complications. We appreciated the very short time between the submission of the paper and its publication on line on your site.

I am very glad to say that the peer review process is very successful and fast and support from the Editorial Office. Therefore, I would like to continue our scientific relationship for a long time. And I especially thank you for your kindly attention towards my article. Have a good day!

"We recently published an article entitled “Influence of beta-Cyclodextrins upon the Degradation of Carbofuran Derivatives under Alkaline Conditions" in the Journal of “Pesticides and Biofertilizers” to show that the cyclodextrins protect the carbamates increasing their half-life time in the presence of basic conditions This will be very helpful to understand carbofuran behaviour in the analytical, agro-environmental and food areas. We greatly appreciated the interaction with the editor and the editorial team; we were particularly well accompanied during the course of the revision process, since all various steps towards publication were short and without delay".

I would like to express my gratitude towards you process of article review and submission. I found this to be very fair and expedient. Your follow up has been excellent. I have many publications in national and international journal and your process has been one of the best so far. Keep up the great work.

We are grateful for this opportunity to provide a glowing recommendation to the Journal of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy. We found that the editorial team were very supportive, helpful, kept us abreast of timelines and over all very professional in nature. The peer review process was rigorous, efficient and constructive that really enhanced our article submission. The experience with this journal remains one of our best ever and we look forward to providing future submissions in the near future.

I am very pleased to serve as EBM of the journal, I hope many years of my experience in stem cells can help the journal from one way or another. As we know, stem cells hold great potential for regenerative medicine, which are mostly used to promote the repair response of diseased, dysfunctional or injured tissue using stem cells or their derivatives. I think Stem Cell Research and Therapeutics International is a great platform to publish and share the understanding towards the biology and translational or clinical application of stem cells.

I would like to give my testimony in the support I have got by the peer review process and to support the editorial office where they were of asset to support young author like me to be encouraged to publish their work in your respected journal and globalize and share knowledge across the globe. I really give my great gratitude to your journal and the peer review including the editorial office.

I am delighted to publish our manuscript entitled "A Perspective on Cocaine Induced Stroke - Its Mechanisms and Management" in the Journal of Neuroscience and Neurological Surgery. The peer review process, support from the editorial office, and quality of the journal are excellent. The manuscripts published are of high quality and of excellent scientific value. I recommend this journal very much to colleagues.

Dr.Tania Muñoz, My experience as researcher and author of a review article in The Journal Clinical Cardiology and Interventions has been very enriching and stimulating. The editorial team is excellent, performs its work with absolute responsibility and delivery. They are proactive, dynamic and receptive to all proposals. Supporting at all times the vast universe of authors who choose them as an option for publication. The team of review specialists, members of the editorial board, are brilliant professionals, with remarkable performance in medical research and scientific methodology. Together they form a frontline team that consolidates the JCCI as a magnificent option for the publication and review of high-level medical articles and broad collective interest. I am honored to be able to share my review article and open to receive all your comments.

“The peer review process of JPMHC is quick and effective. Authors are benefited by good and professional reviewers with huge experience in the field of psychology and mental health. The support from the editorial office is very professional. People to contact to are friendly and happy to help and assist any query authors might have. Quality of the Journal is scientific and publishes ground-breaking research on mental health that is useful for other professionals in the field”.

Dear editorial department: On behalf of our team, I hereby certify the reliability and superiority of the International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews in the peer review process, editorial support, and journal quality. Firstly, the peer review process of the International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews is rigorous, fair, transparent, fast, and of high quality. The editorial department invites experts from relevant fields as anonymous reviewers to review all submitted manuscripts. These experts have rich academic backgrounds and experience, and can accurately evaluate the academic quality, originality, and suitability of manuscripts. The editorial department is committed to ensuring the rigor of the peer review process, while also making every effort to ensure a fast review cycle to meet the needs of authors and the academic community. Secondly, the editorial team of the International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews is composed of a group of senior scholars and professionals with rich experience and professional knowledge in related fields. The editorial department is committed to assisting authors in improving their manuscripts, ensuring their academic accuracy, clarity, and completeness. Editors actively collaborate with authors, providing useful suggestions and feedback to promote the improvement and development of the manuscript. We believe that the support of the editorial department is one of the key factors in ensuring the quality of the journal. Finally, the International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews is renowned for its high- quality articles and strict academic standards. The editorial department is committed to publishing innovative and academically valuable research results to promote the development and progress of related fields. The International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews is reasonably priced and ensures excellent service and quality ratio, allowing authors to obtain high-level academic publishing opportunities in an affordable manner. I hereby solemnly declare that the International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews has a high level of credibility and superiority in terms of peer review process, editorial support, reasonable fees, and journal quality. Sincerely, Rui Tao.

Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions I testity the covering of the peer review process, support from the editorial office, and quality of the journal.

Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions, we deeply appreciate the interest shown in our work and its publication. It has been a true pleasure to collaborate with you. The peer review process, as well as the support provided by the editorial office, have been exceptional, and the quality of the journal is very high, which was a determining factor in our decision to publish with you.

The peer reviewers process is quick and effective, the supports from editorial office is excellent, the quality of journal is high. I would like to collabroate with Internatioanl journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews journal clinically in the future time.

Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions, I would like to express my sincerest gratitude for the trust placed in our team for the publication in your journal. It has been a true pleasure to collaborate with you on this project. I am pleased to inform you that both the peer review process and the attention from the editorial coordination have been excellent. Your team has worked with dedication and professionalism to ensure that your publication meets the highest standards of quality. We are confident that this collaboration will result in mutual success, and we are eager to see the fruits of this shared effort.

Dear Dr. Jessica Magne, Editorial Coordinator 0f Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions, I hope this message finds you well. I want to express my utmost gratitude for your excellent work and for the dedication and speed in the publication process of my article titled "Navigating Innovation: Qualitative Insights on Using Technology for Health Education in Acute Coronary Syndrome Patients." I am very satisfied with the peer review process, the support from the editorial office, and the quality of the journal. I hope we can maintain our scientific relationship in the long term.

Dear Monica Gissare, - Editorial Coordinator of Nutrition and Food Processing. ¨My testimony with you is truly professional, with a positive response regarding the follow-up of the article and its review, you took into account my qualities and the importance of the topic¨.

Dear Dr. Jessica Magne, Editorial Coordinator 0f Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions, The review process for the article “The Handling of Anti-aggregants and Anticoagulants in the Oncologic Heart Patient Submitted to Surgery” was extremely rigorous and detailed. From the initial submission to the final acceptance, the editorial team at the “Journal of Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions” demonstrated a high level of professionalism and dedication. The reviewers provided constructive and detailed feedback, which was essential for improving the quality of our work. Communication was always clear and efficient, ensuring that all our questions were promptly addressed. The quality of the “Journal of Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions” is undeniable. It is a peer-reviewed, open-access publication dedicated exclusively to disseminating high-quality research in the field of clinical cardiology and cardiovascular interventions. The journal's impact factor is currently under evaluation, and it is indexed in reputable databases, which further reinforces its credibility and relevance in the scientific field. I highly recommend this journal to researchers looking for a reputable platform to publish their studies.

Dear Editorial Coordinator of the Journal of Nutrition and Food Processing! "I would like to thank the Journal of Nutrition and Food Processing for including and publishing my article. The peer review process was very quick, movement and precise. The Editorial Board has done an extremely conscientious job with much help, valuable comments and advices. I find the journal very valuable from a professional point of view, thank you very much for allowing me to be part of it and I would like to participate in the future!”

Dealing with The Journal of Neurology and Neurological Surgery was very smooth and comprehensive. The office staff took time to address my needs and the response from editors and the office was prompt and fair. I certainly hope to publish with this journal again.Their professionalism is apparent and more than satisfactory. Susan Weiner