AUCTORES

Globalize your Research

Review Article | DOI: https://doi.org/10.31579/2637-8892/286

*Corresponding Author: Asmin Yurtsever, MSc Social Sciences, Clinical Psychology Leiden University the Netherlands.

Citation: Asmin Yurtsever, (2025), COVID-19 Incidence and Post-COVID Syndrome in Mental Health Disorders: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analyses, Psychology and Mental Health Care, 9(3): DOI: 10.31579/2637-8892/286

Copyright: © 2025, Asmin Yurtsever. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received: 05 June 2024 | Accepted: 23 January 2025 | Published: 03 March 2025

Keywords: covid-19 infection; post-covid syndrome; mental health disorders; long covid; covid-19

Unveiling the connection between mental health and COVID-19, this study delves into pre-existing disorders' impact on susceptibility and post-COVID syndrome. By meticulously reviewing 29 publications, including 52 effect-size estimates from renowned databases, intriguing insights emerge. Surprisingly, individuals with mental health disorders don't exhibit a higher risk of COVID-19 infection. However, the study unveils a compelling revelation - they face a heightened likelihood of post-COVID syndrome. While SARS-CoV-2 infection risk isn't elevated in this group, vulnerability to post-COVID complications prevails. With a profound grasp of limitations and strengths, the findings ripple with implications, urging greater support and care for this resilient population. By recognizing their unique needs, we can pave the way for better health outcomes in a post-pandemic world.

The Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic crisis rapidly escalated into a global pandemic, with more than 767 million individuals infected and 6.9 million deaths as of June 2023 (World Health Organization [WHO], 2023). The pandemic resulted in a burden of potential years of life lost over a decade and has indeed influenced our lives in one way or another. When the pandemic escalated quickly, researchers started investigating factors that may cause some individuals to be more vulnerable (Solis et al., 2020). Literature on past pandemics and natural disasters suggests that numerous factors could make it more likely for people with mental illnesses to contract COVID-19. These vulnerability factors include insomnia, higher prevalence of somatic comorbidities, impaired immune system, chronic stress exposure, poor health behavior, difficulties in evaluating health information and adhering to preventive behaviors, limitations in access to health care, homelessness, or living in areas where the risk of contagion is higher. All of these are related to infection risk and disease course and are frequently present in people who have poor mental health (Chireh et al., 2019; Chrousos, 2009; Shinn & Viron, 2020). Some researchers (e.g., Shinn & Viron, 2020; Wang et al., 2021b) have expressed their concerns that people with a pre-existing mental health disorder may be at a higher risk of COVID-19 infection and that the outcomes of the disease may be worse. Although, before the COVID-19 pandemic, it was estimated that 20-25% of adults are suffering from mental health disorders (450 million globally, 84 million, i.e., 1 out of 6, in the EU (European Union) countries; OECD, 2018), research on the potential effects of (pre-existing) mental health disorders on COVID-19 infection risk, and outcomes of the infection are not yet fully understood. Existing literature on the relationship between COVID-19 susceptibility and various types of mental health disorders is scarce and provides inconsistent findings. A South Korean population-based study found no significant differences in COVID-19 infection rates between psychiatric patients and the general population (Lee et al., 2020); in contrast, a US cohort found that having a psychiatric diagnosis may be a unique risk factor for infection (Taquet et al., 2020). This is in line with three other studies reporting an elevated risk of testing positive for COVID-19 (Liu et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021b; Yang et al., 2020). Nevertheless, Goldenberg et al. (2022) found a lower infection rate among people with a history of psychiatric hospitalization, particularly those with a history of drug or alcohol abuse. Similar results were found in a large-scale cohort study in Israel (Tzur-Bitan et al., 2022), a large cohort study in the USA (Egede et al., 2021), and a population-based study conducted in the UK (van der Meer et al., 2020). It is also controversial whether individuals with different mental health disorders have various susceptibility risks to a COVID-19 infection. Studies seem to differ in their findings. It was hypothesized that people with schizophrenia might be more susceptible to transmissions of COVID-19 (Fonseca et al., 2020; Kozloff et al., 2020; Moreno et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021b) for several reasons. For example, patients with schizophrenia have a dysregulated immune system (Rodrigues-Amorim et al., 2018), cognitive impairments, lower risk awareness, and barriers to adequate housing (Yao et al., 2020a) and timely access to preventative health care (Knaak et al., 2017), poverty (Burns et al., 2014) and difficulties adopting and adhering to the protective measures (Maguire et al., 2019) due to impairments in insight and decision-making capacity (Larkin & Hutton, 2017). However, Tzur-Bitan et al. (2021) and Texeria et al. (2021) reported contradicting results. They showed that individuals with schizophrenia were less likely to be tested positive for COVID-19, while Merzon et al. (2021) found no significant association. Similar to the relationship between schizophrenia and COVID-19 infection, the relationship between mood disorders, anxiety disorder, neurodevelopmental disorders, substance use disorder, and COVID-19 risk is also unclear. For example, some studies showed increased susceptibility to COVID-19 in people with mood and anxiety disorders (Neelam et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021b), substance abuse disorders (SUD) such as tobacco use disorder, alcohol use disorder, cannabis use disorder, injected drug use disorder, cocaine use disorder, and opioid use disorder (Wang et al., 2021a), and attention-deficit/hyperactive disorder (ADHD; Breaux et al., 2021; Cohen et al., 2022; Merzon et al., 2021, Neelam et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021b). On the contrary, other studies reported lower rates of COVID-19 infection in people with mood disorders (Texeria et al., 2021) and drug or alcohol abuse (Goldberger et al., 2022). In addition, some studies did not find a significant positive relationship between the COVID-19 infection rate and mental health disorders; for example, people with depression or anxiety (Ceban et al., 2021), or autism spectrum disorder (ASD; Merzon et al., 2021). In a nutshell, the existing literature on the effects of (pre-existing) various mental health disorders in COVID-19 susceptibility is not only scarce but also inconsistent. To better understand how different mental health disorders are affected by the virus, a systematic review is needed.

Pre-Existing Mental Health Disorders and Post-COVID Syndrome

After 2.5 years, the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic remains a worldwide health problem. Illness severity and its outcomes vary from person to person. Yet, recent studies demonstrated that an increasing number of patients experience prolonged symptoms of the COVID-19 virus (Our World in Data, 2022; Petersen et al., 2021). Post-COVID syndrome, also known as a long-COVID condition, is a complicated and increasingly recognized illness. It is characterized by prolonged diverse symptoms in which some infected patients do not recover for several weeks or months after the onset of COVID-19 infection (Nabavi, 2020; WHO, 2022). Post-COVID syndrome has recently been reported to cause a variety of neurological and mental symptoms such as fatigue, chest pain, breathlessness, body aches, cognitive impairment, insomnia, headaches, anxiety, and depression (Carfi et al., 2020; Chopra et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2021). In addition to these symptoms, those with post-COVID syndrome reported a diminished quality of life, employment problems, issues with their physical and cognitive abilities, and difficulties participating in society (Aiyegbusi et al., 2021; Tobacof et al., 2022). According to Carfi et al. (2021)’s underestimated calculations, at least 10% of COVID-19 survivors suffer from persistent COVID-19 symptoms, which means approximately 6 million people are at risk of post-COVID syndrome globally. Further, according to the U.K.'s Office for National Statistics (2022), post-COVID syndrome symptoms negatively impacted 1.6 million people (73% of those with self-reported long COVID). Among them, 333,000 people reported that their capacity to carry out daily activities had been restricted a lot. The research on post-COVID syndrome has increased, yet the patient profile, associated problems, long-term effects, and the timeline of the disease remain unknown (d'Ettorre et al., 2022). According to limited observational data, patients who require intensive care unit (ICU) admission and/or ventilatory support appear to be at an increased risk of developing post-COVID syndrome (Halpin et al., 2021), even though sequelae are also seen in individuals with mild to moderate symptoms (Davis et al., 2021; Lemhöfer et al., 2021). It is also known that comorbidities such as cancer, diabetes, heart disease, chronic arterial hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, and alcohol and tobacco addiction are correlated with the severity and mortality of COVID-19 (de Miranda et al., 2022; Panda et al., 2022; Sargin Altunok et al., 2022; Zhu et al., 2022). Although the prognosis of the novel post-COVID syndrome is unknown, it is likely to be determined by the comorbid conditions, the severity of clinical symptoms, and treatment response. Recently, de Miranda et al. (2022) showed that the symptoms mentioned earlier were correlated with the severity of the disease, and the severity of acute infection mainly determined the duration of symptoms in post-COVID drome. Thus far, the attempts to identify mutual characteristics of patients with post-COVID syndrome have yielded somewhat inconsistent findings. For instance, Sudre et al. (2021) followed more than 4000 COVID patients. They identified a number of factors that anticipated post-COVID syndrome, such as being over 70 years old, being female, having more than five symptoms during the first week of illness, and having comorbidities. However, Cirulli et al. (2020) revealed that the post-COVID syndrome risk factor was having more than five symptoms during the disease course, not sex or comorbidities. Similarly, Stavem et al. (2021) conducted a four-month follow-up study with 434 COVID-19 patients and found that the presence of at least 10 symptoms during acute COVID-19 was found to be a risk factor for post-COVID syndrome. Although some studies concluded that having comorbid disorders is a risk factor for post-COVID syndrome, studies that investigated mental health disorders as comorbid disorders are scarce. Townsend et al. (2020) demonstrated that COVID-19 patients who experienced persistent fatigue 10 weeks after discharge were more likely to be females and have a history of being diagnosed with anxiety or depression or taking antidepressants. Similarly, Poyraz et al. (2020) found that female sex and history of psychiatric illness were risk factors for experiencing persistent COVID-19 symptoms. The lack of information on why some people suffer from post-COVID syndrome and how the human body recovers from post-COVID syndrome is still an ongoing challenge for science, with inconsistent data thus far.

Research Objectives and Implications

Given the complex interactions between COVID-19 infection and mental disorders, a thorough, meticulous meta-analysis is required to evaluate the overall and type-specific risk of mental health disorders for COVID-19 infection and clinical outcomes. Furthermore, there is a need for studies to review several types of mental disorders to understand better who is affected by the virus most and how the COVID-19 pandemic is impacting vulnerable populations. The pandemic has clearly given rise to a new wave of chronic, disabling problems that require considerable attention from the scientific and medical communities, and the absence of knowledge regarding why and how the human body is affected by the virus is a critical gap in the literature. The existing literature on post-COVID syndrome is limited, especially when it comes to who is affected and to what extent. However, its significant effects, from raised healthcare expenses to productivity losses on people, societies, and countries, are clear. Given the swiftly increased number of people presenting with COVID-19 sequelae, the acquisition of the most correct knowledge about the illness is a necessary step for humans to survive this pandemic. Nonetheless, to the best of my knowledge, no meta-analysis systematically investigated the relationship between pre-existing mental disorders subtypes (e.g., psychotic disorders, neurodevelopmental disorders, mood disorders, anxiety, and substance abuse disorders) and COVID-19 infection rate and associated post-COVID syndrome. The aim of this study is to assess whether preexisting mental health disorders are associated with a higher risk of COVID-19 susceptibility and post-COVID syndrome. Therefore, I conducted a meta-analysis to assess the relationship between mental health disorders and the risk of COVID-19 infection and disease outcomes for general and type-specific mental health disorders. I have two main objectives: (1) I calculate the pooled overall estimates of the association between mental and neurological disorders and COVID-19 susceptibility, (2) I evaluate the relationship between specific mental health disorders and the risk of developing persistent covid outcomes.

Hypotheses

(1) People with pre-existing mental disorders are more prone to be infected with the COVID-19 virus relative to people without pre-existing existing mental health disorders.

(2) It is expected that people with pre-existing mental health disorders are more likely to suffer from post-COVID syndrome relative to people without pre-existing mental health disorders.

Registration and Protocol

This systematic review with meta-analyses is a sub-project of a larger research project, and the protocol for the project has been preregistered in PROSPERO (ID: CRD42021269432) and the Open Science Foundation (https://osf.io/35jhm/registrations). This meta-analysis complied with MOOSE (Stroup et al., 2000) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2009).

Search Strategy and Study Selection

This systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted using searches in PubMed, Web of Science, and the preprint server Biorxiv.org, which was supplemented with a non-systematic search in Google Scholar. According to Bramer et al. (2017), this is the optimal database combination for a systematic literature search. Keywords such as (“COVID 19” OR COVID-19 OR COVID19 OR “SARS CoV-2” OR “Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2” OR coronavirus OR SARS-CoV OR SARS-CoV-2) AND (psychiatry OR mental OR “clinical psychology” OR substance use OR alcohol OR “illegal drugs” OR addiction OR dependence OR depress* OR mood OR “adjustment disorder” OR Bipolar OR mania OR schizophrenia OR psychosis OR psychotic OR anxi* OR PTSD OR “post-traumatic stress disorder” OR “adjustment disorder” OR “somatic symptom disorder” OR “eating disorders” OR “Binge eating” OR anorexia OR ADHD OR “attention deficit hyperactivity disorder” OR “conduct disorder”) were used to filter the intended studies from inception up to August 11, 2022. Papers written in English, Dutch, Spanish, German, or French were included in the search. Additionally, reference lists of reviews and meta-analyses that might meet the inclusion criteria were hand-searched from the found eligible articles for more potential articles. Duplicate articles were removed using EndNote 20. The articles have independently assessed for their eligibility for inclusion. The first decision on eligibility was based on titles and abstracts of the potential articles and the second (final) decision was based on full texts. Then the inclusion and exclusion decisions were cross-checked, and any discrepancy was solved by discussion.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The articles were included if they (1) reported SARS-CoV-2 infection rate and/or course of COVID-19 for patients with preexisting mental disorders vs. controls, (2) were written in English, German, French, Spanish, Arabic, or Dutch, and (3) patients were diagnosed with mental disorders according to DSM or ICD. The articles were excluded if (1) the full text could not be retrieved or (2) no relevant outcome data could be extracted, even after the corresponding authors of the article were contacted, (3) no original data were reported (e.g., opinion papers, reviews) or if (4) the mental health disorder diagnoses were based on self-report questionnaires. If the articles reported overlapping data sets, only the most comprehensive information in line with this study's purpose was included to avoid data duplication.

The exposure of interest was pre-existing mental health disorders assessed according to diagnostic systems such as ICD 9 or 10 (World Health Organization, 1979, 1993) or DSM-4 or 5 (American Psychiatric Association, 1992, 2013). The outcomes of interests were (1) a relative infection rate in people with mental health disorders that were presented as the percentage of SARS-CoV-2 positive tests, and (2) a COVID-19 outcome variable, defined by a post-COVID syndrome, in other words, long COVID.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

The extraction included basic study information such as first author, year of publication, which country the study was conducted in, total sample size, number of participants with mental disorders, number of participants who developed the outcome of interest both in control and focus groups, psychiatric disorders, comorbidities, mean or median age, gender distribution, study design, the outcome of interests, outcome data as raw numbers or effect-size estimates, and corresponding 95% Confidence Intervals (95% CI), and adjusted or unadjusted values.

The data extraction and methodological quality assessment of selected studies were independently conducted by the author and the supervisor by using The Quality Assessment Tool for Cross-Sectional Studies, which is a recommended and updated tool by the United States National Institute of Health (2021).

Statistical Analyses

The analyses were performed in JASP version 14.1, and summary tables on the characteristics of eligible papers were created. The relationship between preexisting (both current and lifetime) mental disorders and SARS-CoV-2 infection rates and the post-COVID syndrome was assessed by pooling data by means of Random-effects meta-analyses. Both classical meta-analyses and Bayesian meta-analyses were used to analyze the data.

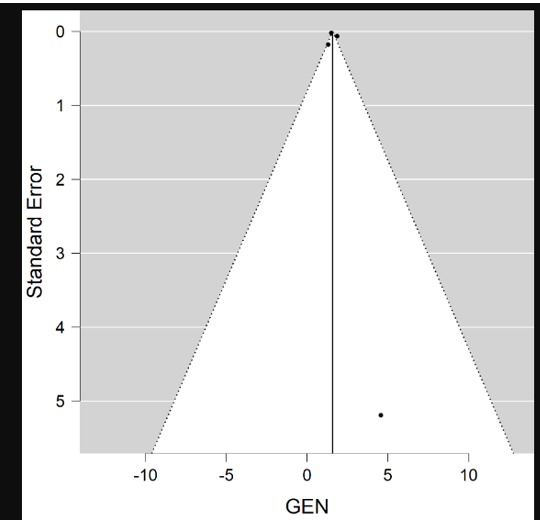

Pooled data, accompanied by the 95% confidence interval (95% CIs), were analyzed. A p-value of < .05 was set as a statistical significance point. Cochran’s Q2 heterogeneity test and I2 statistic were used to assess statistical heterogeneity. Kendall’s Tau (Sterne et al., 2001) rank correlation test and Egger test were used to assess publication bias, and funnel plot asymmetry was used for visual inspection. When heterogeneity in outcome was detected, meta-regression and subgroup analyses were performed to explore study characteristics that could explain the heterogeneity.

Study Selection and Characteristics

The initial database search yielded 67901 studies, and 42175 remained after removing duplicates. After screening titles and abstracts, 220 studies were found to be eligible. Among these eligible studies, 181 were further excluded after the full-text screening. Finally, 29 articles were eligible and included in this analysis (total sample size N = 85.064.921, average n per study = 2.933.273, with a range from 96 to 73.099.850; see Figure 1). Table A1 in the appendix lists all the articles included for full-text assessment and reasons for inclusion and exclusion. The flow chart (see Figure 1) summarizes the identification, screening, and inclusion of studies. Out of the previously mentioned 29 included articles, 25 examined the effect of pre-existing mental health disorders on the COVID-19 infection rate, and 4 assessed the effect of pre-existing mental health disorders on the post-COVID syndrome. The selection of articles for inclusion in the study was constrained by limited availability. Nonetheless, Cheung and Vijayakumar (2016) have posited the feasibility of employing a minimum of two studies when conducting a meta-analysis. Their examination of the requisite number of studies for such analyses revealed a spectrum spanning from three to 526 studies.

Table 1 provides demographic and clinical information on the samples of the studies included. Table 2 provides further information on the assessment of predictor variables, outcome variables, and study characteristics. The sample size ranged from 96 to 73099850 for the articles on infection risk, and from 646 to 5017431 for the articles on the post-COVID syndrome. The median sample size for infection risk was 48449, and 533821 for the post-COVID syndrome. The average age of the included samples ranged between 9 and 81 years. The percentage of females per sample ranged from 16 to 64%. The country of assessment varied, with the US being the most significant source of research.

Figure 1: Flowchart on identification, screening, and inclusion of eligible publications

| Articles | N | Age |

DiscussionThe present meta-analysis aimed to examine the relationship between pre-existing mental health disorders and (1) COVID-19 susceptibility, and (2) post-COVID syndrome. To investigate this, the current literature was systematically reviewed. Susceptibility for COVID-19 Infection and Mental Health Disorders The first hypothesis states that people with pre-existing mental disorders are more prone to be infected with the COVID-19 virus. To investigate this, the relationship between the COVID-19 infection rate and different mental disorders was examined. Even though some research has shown that having pre-existing mental health disorders puts individuals at a higher risk of getting infected by the COVID-19 virus (Breaux et al., 2021; Cohen et al., 2022; Fonseca et al., 2020; Kozloff et al., 2020; Merzon et al., 2021; Moreno et al., 2020; Neelam et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021b), the results of the current study did not support these findings. Post-COVID Syndrome and Mental Health Disorders The second hypothesis states that people with pre-existing mental health disorders are more likely to suffer from post-COVID syndrome relative to people without pre-existing mental health disorders. In line with the hypothesis, the results showed that people with pre-existing mental health disorders are more likely to suffer from post-COVID syndrome. Similar results were seen in previous studies that examined the relationship between pandemics (Zhang et al., 2020) or chronic illnesses resulting from viral or non-viral viruses (Hickie et al., 2006) and mental health disorders. For example, both Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) cause some persisting symptoms after infection. One of the long-lasting effects of SARS includes chronic fatigue syndrome, which has previously been found to have increased incidence in people with mental health disorders (Hickie et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2020). Given the shared symptoms of these diseases, it is possible to see similar effects in COVID-19 survivors. Alternatively, previous studies indicate that with some mental health disorders, such as mood disorders and substance abuse disorders, there is a heightened prevalence of somatic comorbidities, including diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease (Barton et al., 2020; Coello et al., 2019; Dalack & Roose, 1990; Goldstein et al., 2020; Mansur et al., 2019). These somatic comorbidities are known to be associated with more severe COVID-19 manifestations (Sargin Altinok et al., 2022; Zaman et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2021). Also, the recent study by de Miranda et al. (2022) illustrated that the severity of the disease was the main determinant of the duration of the post-COVID syndrome. Although the exact mechanisms that explain the relationship between mental health disorders and post-COVID syndrome are not yet known, above mentioned associations may explain the underlying association between mental health disorders and post-COVID syndrome. Implications, Future Research, and Recommendations The results of this study have several implications. From a research perspective, this systematic review and meta-analysis provided a valuable contribution to the literature by combining multiple studies and analyzing the above-mentioned associations. As mentioned earlier, there seems to be a discourse on the relationship between pre-existing mental health disorders and COVID-19 susceptibility, with some articles increasing but other research stating it is decreasing, and other literature concluding that there is no significant relation between the two. Combining, summarizing, and analyzing multiple individual pieces of research enabled us to have more representative and reliable results. The actual relationship between pre-existing mental health disorders and COVID-19 susceptibility has been better identified. Additionally, this study revealed that individuals with pre-existing mental health disorders are more prone to suffer from the prolonged effects of COVID-19. This study, therefore, provides a more comprehensive picture of the effects of pre-existing mental health disorders on COVID-19 susceptibility and on post-COVID syndrome. These findings have not been reported broadly elsewhere in the literature and could serve as a starting point for further research on the post-COVID syndrome. Future research, on the other hand, should focus on the effects of individual mental health disorders, and whether and how they play a role in these relationships. This meta-analysis included articles from December 2019 to August 11, 2022. The relevant research on the topics would increase in the following years, adding even larger sample sizes and more diverse data to be explored. Although large samples with well-powered studies were included, due to the limited published data, it was not possible to run moderator and sub-group analyses. Therefore, future studies should consider including more studies to further explore potential relationships. From a preventive perspective, patients with mental health disorders should be considered at high risk for post-COVID syndrome. Policymakers should consider these results in new healthcare plans, insurance, vaccination policies, and health education campaigns, specifically in areas with limited importance and/or access to care for this vulnerable group. Governments and healthcare providers should work on interventions to decrease stigma related to mental health disorders and infections, and provide routine check-ups, especially during pandemics and epidemics. Previous research on disasters demonstrated that up to 40% of affected people seeking mental health support during or after a disaster have pre-existing mental health disorders (North & Pfefferbaum, 2013). It is also shown that the COVID-19 pandemic caused further adverse effects on mental health among people with pre-existing mental health disorders (Pan et al., 2020; Rheenen et al., 2020). Healthcare workers should be more aware of risk among high-risk groups and inform these patients about the effects of persistent symptoms of COVID-19, and better guide them on medical and mental aftercare. Although previous research (Chit et al., 2009) pointed out that the SARS virus could cause significant prolonged symptoms among people with and without a history of mental health disorders, we also witnessed how most countries poorly managed one of the biggest pandemics of humankind. New infectious epidemics will rise due to globalization (Wong, & Yuen, 2006), which means this pandemic is not the last one. Some precautions should be taken to better protect people with mental health disorders. While more research on pandemics is being conducted, current knowledge of disaster response management should be improved and applied when necessary. From a mental health treatment perspective, the results are relevant to the treatment of several mental health disorders. Considering people with mental health disorders are more prone to suffer from post-COVID syndrome and physical symptoms of this syndrome make it harder for individuals to travel, modern ways of digital communication allow them to receive the necessary support, treatment, intervention, and education in their homes (Salawu et al., 2020; Zhang, & Ho, 2017). Additionally, during the high peak season, many governments restricted face-to-face interactions and set social distancing and quarantining requirements. Therefore, during the COVID-19 pandemic, online consultations and smartphone telehealth apps (telerehabilitation and telepsychiatry) have rapidly increased (Li et al., 2020; Yao et al., 2020b). Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is recommended for many mental health disorders, such as mood and anxiety disorders and chronic fatigue syndrome (Castell et al., 2011; Cuijpers et al., 2016). Studies also showed that online CBT is an effective and efficient treatment tool with reduced travel time and cost and increased accessibility (Prvu Bettger & Resnik, 2020; Soh et al., 2020; Vugts et al., 2018). Thus, considering restrictive physical health consequences of post-COVID syndrome (e.g., tiredness and fatigue, and chronic fatigue syndrome), online treatment tools should be encouraged to treat people with post-COVID syndrome, Strengths and Limitations To my knowledge, this is the first comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis to provide a quantitative estimate between the type-specific mental health disorders and COVID-19 susceptibility, as well as post-COVID syndrome risk in COVID-19 patients. The results of this meta-analysis were in line with a previous meta-analysis (Ceban et al., 2021). However, this study has a more robust analytical approach. First, the presented results were stratified by mental health disorder categories when possible. Second, this study has a strong methodological design in accordance with The Quality Assessment Tool for Cross-Sectional Studies (United States National Institute of Health, 2021). Third, overall heterogeneity and the sample size were high. Lastly, this study endeavored to avoid including overlapping datasets. The limitations of this systematic review and meta-analysis should be acknowledged. First, it is important to consider the limited number of studies included for the post-COVID syndrome. Hence the interpretation of the results does not provide a complete picture of stratified mental health disorders. Second, mental health disorders were defined according to ICD or DSM codes in insurance or government data. Although these are widely used, for better insurance benefits, some patients could be misdiagnosed, or there could be wrongly entered data in patient records. These administrative data may have high specificity but varied sensitivity (Wilchesky et al., 2004). Third, some studies have inadequately differentiated mental health disorders (i.e., they only stated mood disorders but not major depressive disorders or bipolar disorders), which could impact the result as they could show different characteristics. Although some studies had better distinctions than others, they were all grouped into the most appropriate category. Even though this study has high heterogeneity and sample size, heterogeneity could not always be explained with moderator and sub-group analyses. At last, the samples consisted of an unequal gender ratio and varying ages, and one study had no data on age and gender. This could cause limitations for the current study, while gender and age differences could result in experiencing the disease differently, because they may play a role in smoking behaviors and the prevalence of comorbidities (Mukherjee & Pahan, 2021; Ya'qoub et al., 2021). Summary and ConclusionThis study consists of two meta-analyses investigating the relationship between pre-existing mental health disorders and susceptibility to COVID-19 (N = 83.962.693), and post-COVID syndrome (N = 1.102.228). The results of this study can be described as partially unexpected. The first analysis revealed that the infection rate for SARS-CoV-2 infection was not significantly different among people with and without pre-existing mental health disorders. However, the second analysis revealed that people with pre-existing mental health disorders are more likely to suffer from the post-COVID syndrome. These results suggest that although people with pre-existing mental health disorders are not statistically more at risk in terms of susceptibility to SARS-coV-19 infection, they are statistically more prone to suffer from persistent COVID-19 symptoms. Therefore, they should be categorized as an at-risk group based on pre-existing mental illness conditions, similar to people with pre-existing somatic conditions (e.g., cardiovascular disease, obesity). It is essential to note the increased prevalence of mental health disorders due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Taquet et al., 2021), as well as the emergence of the post-COVID syndrome, which can also cause mental health symptoms. In all, the results point out that public health authorities should consider close monitoring and adequate aftercare in patients with mental health disorders who got COVID-19. Future research should address how different mental health disorders interact with the post-COVID syndrome and how the COVID-19 infection influences the trajectory of the current mental health disorders. References

Virginia E. Koenig

Delcio G Silva Junior

Ziemlé Clément Méda

Mina Sherif Soliman Georgy

Layla Shojaie

Sing-yung Wu

Orlando Villarreal

Katarzyna Byczkowska

Anthony Kodzo-Grey Venyo

Pedro Marques Gomes

Bernard Terkimbi Utoo

Prof Sherif W Mansour

Hao Jiang

Dr Shiming Tang

Raed Mualem

Andreas Filippaios

Dr Suramya Dhamija

Bruno Chauffert

Baheci Selen

Jesus Simal-Gandara

Douglas Miyazaki

Dr Griffith

Dr Tong Ming Liu

Husain Taha Radhi

S Munshi

Tania Munoz

George Varvatsoulias

Rui Tao

Khurram Arshad

Gomez Barriga Maria Dolores

Lin Shaw Chin

Maria Dolores Gomez Barriga

Dr Maria Dolores Gomez Barriga

Dr Maria Regina Penchyna Nieto

Dr Marcelo Flavio Gomes Jardim Filho

Zsuzsanna Bene

Dr Susan Weiner

Lin-Show Chin

Sonila Qirko

Luiz Sellmann

Zhao Jia

Thomas Urban

Cristina Berriozabal

Dr Tewodros Kassahun Tarekegn

Dr Shweta Tiwari

Dr Farooq Wandroo

Dr Anyuta Ivanova

Dr David Vinyes

Gertraud Teuchert-Noodt

Dr Elvira Farina

Dr Oleg Golyanovski

Dr Susan Anne Smith

Dr Farahnaz Fallahian

Dr Victor Olagundoye

Dr Susan Anne Smith

Dr Eric S Nussbaum

Hala Al Shaikh

Dr Rakhi Mishra

Dr Walter F Riesen

Dr Jelle Lettinga

Dariusz Ziora

Dr Ravi Shrivastava

Dr Aline Tollet

Dr Chiara Giuseppina Beccaluva

Dr Claudio Ligresti

Dr Matteo Bonori

Edouard Kujawski

Dr Andriy Sinelnyk |

|---|