AUCTORES

Globalize your Research

Research Article | DOI: https://doi.org/10.31579/2637-8892/215

1 MA in Psychology, Department of Psychology, University Campus at University of Guilan, Rasht, Iran.

2 Assistant Professor of Psychology, Department of Psychology, Faculty of Literature and Humanities, University of Guilan, Rasht, Iran.

3 Assistant Professor of Psychology, Department of Psychology, Faculty of Literature and Humanities, University of Guilan, Rasht, Iran.

*Corresponding Author: Sajjad Rezaei, Assistant Professor of Psychology, Department of Psychology, Faculty of Literature and Humanities, University of Guilan, Rasht, Iran.

Citation: Pourmohseni Shakib SM., Sajjad Rezaei., Ashkan Naseh., (2023), Attachment Styles in Gay Men with Different Sex Roles in A Middle Eastern Country, Psychology and Mental Health Care, 7(3): DOI:10.31579/2637-8892/215

Copyright: © 2023, Sajjad Rezaei. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any mdium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received: 17 March 2023 | Accepted: 31 March 2023 | Published: 19 April 2023

Keywords: homosexual; attachment; avoidance; anxiety; middle east

Background and Aim: Gay men’s identity harbors a secondary sexual role or self-label that can affect many aspects of their lives. Studies have shown that many gay men express a secondary self-label (i.e., top, bottom, and versatile) based on their role during anal intercourse. Considering the unwelcoming social atmosphere and religious and legal restrictions in Iran regarding the issues related to LGBT people, a few studies have been conducted on attachment styles and the quality of relationships with primary caregivers in this sexual minority in Iran. This study hence aimed to compare gay men playing different sexual roles with their heterosexual peers in attachment styles.

Materials and methods: In a causal-comparative research, 197 gay men (30 top, 36 bottom, and 131 versatile) and 49 heterosexual men were selected by snowball and purposive sampling methods to fill out the Revised Adult Attachment Scale (Collins & Read, 1996).

Results: The findings showed that there was a significant difference between versatile gay men and heterosexual men in the avoidance attachment style, as heterosexual men gained a higher mean score in this attachment style. There was also a significant difference between the gay men with different sex roles and heterosexual men in the anxious-ambivalent attachment style, as the bottom gay men obtained the highest mean scores.

Conclusion: The imitation of the generally accepted masculinity criteria by Iranian gay men in an attempt to avoid rejection from parent and peers increases their anxiety levels and may leads to the emergence of the anxious attachment style in them.

Despite the remarkable scientific advances of Iranian researchers in various psychological fields, few studies have been conducted on homosexuality and issues related to this sexual minority mainly due to cultural, social, and political issues in today’s Iranian society; for example, same-sex relationships are considered a crime and subject to strict punishments. This research gap has deprived the Iranian society of psychologists of sufficient and accurate information about this sexual minority and made it difficult for psychiatrists to effectively deal with gay clients and identify their problems. The personal prejudices and biases of therapists, such as homophobia, resulting from living in a patriarchal society sometimes add to the complexity of such situations and problems of gay clients (Pourmohseni Shakib, 2021).

To get to know this sexual minority as much as possible in the context of Iranian society, it is necessary to first address the issues that introduce us to the most fundamental worldview of members of this minority, i.e., how they look at themselves, others, and the surrounding world. Accordingly, this study compares gay men with different sex roles with their heterosexual (straight) peers in terms of attachment styles. Homosexuality is a pattern of romantic, emotional, and sexual attraction between people of the same sex (American Psychological Association, 2019). The identity of gay men includes a secondary sexual self-label that can affect many aspects of their lives, from physical characteristics to preferences for choosing an emotional-sexual partner (Moskowitz, 2008). Sociological, psychological, and general health studies have shown that many gay men express secondary sexual self-label (i.e., top, bottom, and versatile) based on the role they play during anal intercourse, i.e., their sex role (Moskowitz, 2011). It is noteworthy that sex roles deal with how one describes themselves and affect their preferences for sexual positions, while sexual positions in anal relationships refer to sexual practices and behaviors (Kippax & Smith, 2001; Johns & Pingel, 2012). During a same-sex relationship, sexual partners may take different sex roles. This simple rule allows us to distinguish two distinct patterns of sex roles in homosexuals as follows:

One of the differences between homosexuals and heterosexuals is the greater importance of romantic and social relationships for homosexuals (Mohr, 2003; Grossman, D’augelli, & Hershberger, 2008). Despite all the general stereotypes about same-sex relationships, many gay men and lesbian women usually live together for a long time. The data obtained from different resources indicate that 30-60% of gays and 45-80% of lesbians are always engaged in a monogamous romantic relationship (Elizur, 2003; Allan, 2018). A study conducted by Colgan (1987) showed that many homosexuals face intimacy dysfunctions originating from problems with interpersonal communication, unresolved intrapsychic issues, interpersonal stress, and behavioral patterns formed to deal with unresolved stress. According to these concepts, identity and functional disorders in intimate relationships are regarded as efforts made by a person to recover their state of well-being.The attachment theory deals with the need to make close relationships with others. John Bowlby (1969) states that this pervasive need is an evolutionary advantage to ensure closeness between the child and the caregiver in times of danger, anxiety, and ambiguity. Accordingly, a child’s experiences in the relationship with a caregiver form internal working models that indicate how one interacts with themselves and others and how interprets the surrounding world in the face of stressful and threatening situations (Allan, 2018). It is noteworthy that researchers classify attachment in different ways. For example, based on the child's expectations of the caregiver's presence and responsiveness, a sense of comfort to build an intimate relationship with independence and an attitude about being lovable, Ainsworth (1978) introduced three attachment styles: secure, avoidance, and anxious-ambivalent. Although there is a long history of studies on the relationship between attachment styles and the quality of one’s relationships in adulthood, most of these studies have focused on heterosexuals and a few of them have dealt with homosexuals. This is the result of the sovereignty of heteronormative systems in society (Mohr, 2008). Based on a scoping review conducted by Allan (2018), most studies conducted on this subject can be divided into 4 categories. The first category is called “universal attachment dynamics” because they emphasize the universal and dynamic nature of attachment regardless of sexual orientation. Such studies, in fact, argue that homosexuals and heterosexuals share the same structure of attachment dynamics. For example, the findings of Ridge (1998) showed that the frequency of attachment styles in heterosexual and gay samples was similar. The second category, which is known as “particular attachment dynamics”, includes studies emphasizing that gay men face attachment dynamics different from those of heterosexual men due to their special experiences such as homophobia and rejection. For example, Landolt (2004) investigated the independent effect of being rejected by father and peers on predicting anxious attachment in gay men, and Shenkman (2019) studied the relationship between minority stress and higher levels of avoidance attachment style. The third category, known as “the impact of attachment narratives”, includes studies that investigate the effects of problems such as homophobia, homonegative expressions, and heterosexism on patterns of romantic relationships among gay men.For example, Sherry (2007) studied the relationship between internalized homophobia and adulthood attachment and reported that insecure attachment style exhibited the strongest relationship with internalized homophobia, shame, and sense of guilt. The fourth category, titled “Monogamish”, includes studies on attachment dynamics and non-monogamous relationships of gay men. For example, Ramirez (2010) found no sign of avoidance attachment style in gay men with open relationships and Mohr et al. (2013) showed that there was a negative relationship between open relationships and the level of satisfaction with a relationship when a person or their sexual-emotional partner are suffering from mild to severe anxiety. This is consistent with the findings of similar studies conducted on heterosexual couples.Given all challenges toward gay men in Iran, this study hypothesized attachment style of self-identified gay men with different sex roles (top, bottom, and versatile) would differ from attachment style of self-identified heterosexual.

Participants and Procedure

The statistical population consisted of Iranian gay and heterosexual men, especially those living in Rasht and Tehran, in 2019-2020. In a causal-comparative research, gay men and heterosexual men were selected by snowball and purposive sampling methods and compared in term of different adult attachment styles. The reason for selecting these two cities was the easier in-person sampling and data collection. Before the official beginning of the study, the first author met and befriended several gay men by attending their private parties and tried to convince them to participate in a study about the issues and problems related to gay men. The author received a warm welcome from the gay men he met. In addition, the author signed up on a gay dating app named Hornet and followed the gay groups and channels on Telegram, WhatsApp and Instagram. However, the socio-cultural-judicial constraints on homosexuality as well as the abuse of members of this minority by some sexual and mental abusers led to their distrust and unwillingness to participate in the research either in-person or online. There fore, an online questionnaire was developed on Google Forms to be filled out without the need for personal information. The link of this online questionnaire was sent to the participants in two different ways. In the first method, based on snowball sampling, the link was sent to Telegram or WhatsApp accounts of gay men who were identified at parties and private circles and they were asked to send the link to other gay men they knew. In the second method, based on purposive sampling, the author found the personal accounts of gay men on social networks and then sent the questionnaire link after making an introductory interview and obtaining their informed consent. Considering the atmosphere of fear about homosexuality in Iranian society, only 332 (24.11%) questionnaires of the total 1377 questionnaires sent to participants were filled out. The inclusion criteria were being physiologically male based on self-report, self-expression about sexual orientation (gay and heterosexual), and informed consent. In addition, the exclusion criteria were being bisexual or transsexual based on self-report, being physiologically female based on self-report, and being aged under 21 years. Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 49 heterosexual men and 197 gay men (including 30 top, 36 bottom, and 131 versatile) were selected to enter the study. It is noteworthy that the convenience sampling method was used to select participants from among the matched heterosexual men.

Measurement tools:

A personal information form was used to collect data on demographics and sexual self-label of participants. The demographics section contained questions about gender (male, female, or transgender), educational attainment (junior high school, high school diploma, associate’s, bachelor’s, master’s, doctorate, and post-doctorate), age group, order of birth (first, middle, last, or single child), emotional relationship status (engaged, not engaged, or open relationship), marital status (single, married to a woman, or divorced), and email address for receiving the general recommendations of the study. In the sexual self-label section, the participants were asked three simple questions to determine their sexual orientation and sex role. The first question, which aimed to determine the sexual orientation of participants, consisted of three items as follows: heterosexual (attracted to people of the opposite sex), gay (attracted to people of the same sex), and bisexual (attracted to people of both sexes). To add to the accuracy of the information, the second questions was about their romantic (“Exclusively heterosexual”, “Predominantly heterosexual, only incidentally homosexual”, “Predominantly heterosexual, but more than incidentally homosexual”, “Equally heterosexual and homosexual”, “Predominantly homosexual, but more than incidentally heterosexual”, “Predominantly homosexual, only incidentally heterosexual”, and “Exclusively homosexual”). If the participants select one of the items from 0 to 6, they are regarded as heterosexual [0 or 1], bisexual [2 to 4], and gay [5 or 6], respectively (Besharat et al., 2016). To determine the sex role of participants, they were asked which of the sex roles they could better describe. This third question consisted of three items for homosexuals (top, bottom, or versatile) and one item for heterosexuals (none).

Revised Adult Attachment Scale (RAAS): This scale was developed by Collins and Read in 1990 to measure attachment styles. The RAAS initially consisted of 21 items that were later (1996) reduced to 18 items. The items are scored based on a 5-point Likert scale (from Not at all characteristic of me to Very characteristic of me). The items of this scale, such as “In relationships, I often worry that my partner does not really love me”, measure three attachment styles of secure, avoidance, and anxious-ambivalent. Secure attachment style: The caregiver gives predictable and sincere answers to the child and leaves him/her while the child is confident about the caregiver’s availability. Avoidance attachment style: This attachment style refers to the situation in which the child realizes that the caregiver is emotionally distant and physically inaccessible. Avoidant children have little inclination to rely on their caregiver when needed, always keeping a distance between the caregiver and themselves. People with this attachment style believe that no one is available to help them when they are in stressful and threatening situations. Anxious-ambivalent attachment style: This attachment style refers to the situation in which children feel that the caregiver is not aware of their needs and are faced with unpredictable responses from them. Such children are more attached to their caregiver, ask them greater demands, and show less desire to explore the world around them. This attachment style is usually observed in individuals who are not comfortable with emotional closeness (Allan, 2018). This scale also measures three other factors using 18 items. The first factor is “anxiety” that deals with stresses such as fear of being abandoned and not being loved in a relationship, the second factor is “dependence” that measures one’s degree of trust in others and their availability, and the last factor is “closeness” that examines how one feels uncomfortable with intimate relationships (Teixeira, 2019). Collins and Read assessed the reliability of this scale by the repeatability test on a sample of 101 members who filled out the scale at an interval of two months. The correlation between scores on secure, avoidant, and anxiety-ambivalent attachment styles was obtained 0.68, 0.72, and 0.52, respectively (Collins and Read, 1990). In Iran, Pakdaman et al. assessed the reliability of this scale by the repeatability test on a random sample of 100 male and female junior high school students who filled out the scale twice at an interval of one month. The results showed that this scale was reliable at a 95% level of confidence. The construct validity of this scale was also evaluated by divergent or diagnostic validity. At the 0.001 level of significance, the correlation coefficient between subscales was -0.313 and -0.336, respectively. It is noteworthy that the correlation coefficient between “closeness” and “dependence” was equal to 0.264 at the 0.014 level of significance (Pakdaman, 2001; Tardast, 2015).

Statistical analysis:

All statistical analyses were performed in SPSS-24. The multivariate analysis of variance was employed to compare different levels of attachment styles in three groups of gay men and a group of normal heterosexual men. Since matching groups no confounding demographic or background variable was found, there was no need to control their values by analysis of covariance. Considering the sample size of subgroups and the homogeneity of variances, the Games-Howell post-hoc test was used to compare the mean difference between the four groups.

The data obtained from 332 participants were statistically analyzed. Table 1 shows the frequency distribution and percentage of sexual orientation by the gender of participants separately

Table 1: Frequency distribution and percentage of sexual orientation by the gender of participants (n=332)

Based on the exclusion criteria, the participants who stated that they were female or transsexual and the males who reported a bisexual orientation were excluded from the study. Of the remaining 208 gay men, 3.3% of them due to being under 21 years and 1.9% of them because of being categorized as bisexual (based on their answers to the question about romantic affairs) were excluded from the study. As a result, a total of 49 heterosexual men and 197 gay men advanced to the next stage. The results indicated that 30 (15.2%), 36 (18.3%), and 131 (66.5%) of the gay men were playing the role of top, bottom, and versatile, respectively. Table 2 presents the frequency distribution and percentage of age groups for each sexual orientation and role.

Table 2: Frequency distribution and percentage of age groups for each sexual orientation and role

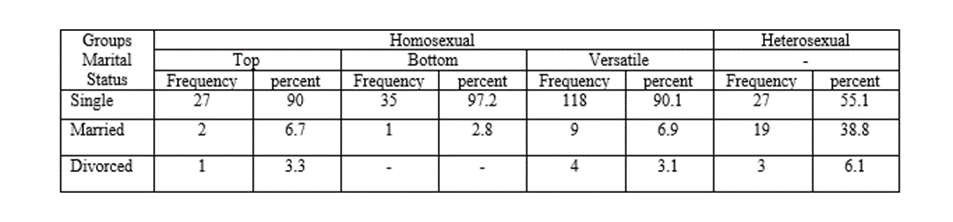

Table 3 shows the frequency distribution and percentage of marital status for each sexual orientation and role. The results showed that the highest rates of marriage and separation were observed among versatile gay men (6.9%) and top gay men (3.3%), respectively.

Table 3: Frequency distribution and percentage of marital status for each sexual orientation and role

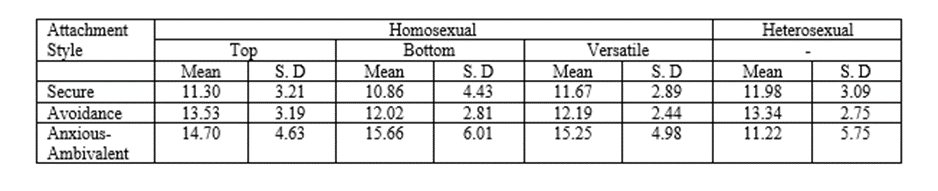

Table 4: The mean and standard deviation of attachment style in studied groups

Levene’s test was employed to compare the research variables in terms of the homogeneity of variance. The results indicated that the F-statistic of Levene’s test to evaluate the homogeneity of variance of variables in study groups was not statistically significant for the avoidance attachment style (F=1.28, P=0.279) and the anxious-ambivalent attachment style (F=1.85, P=0.138). This means that the variance of these variables was homogeneous in the studied groups. By contrast, the F-statistic of Levene’s test was statistically significant for the secure attachment style (F=4.54, P=0.004). Allen and Bennett (2008) suggest that if the homogeneity of variances is not established for one or more dependent variables, it is better to use a stricter alpha or significance level, such as 0.001 than 0.05. Therefore, the significance levels of the -statistic of Levene’s test were processed based on the suggestion of Allen and Bennett (2008).

The Box's M test was used to investigate the homogeneity of the variance-covariance matrix of dependent variables in the studied groups. The results demonstrated that the F-statistic of Box's M test was statistically significant for all attachment styles (F=1.72, Box’s M=32.054, P=0.029). Allen and Bennett (2008) suggest that the Box's M test is resistant to the heterogeneity of variance-covariance matrices when the sample size of each group is greater than 30. In this study, the sample size of all gay and heterosexual groups was greater than 30.

The Games-Howell post-hoc test for unequal variance was also employed for pairwise comparisons of means. The results of Wilks' lambda multivariate analysis of variance showed that there was a significant difference between the groups in attachment styles at the 0.0001 level of significance (Wilks' lambda=0.87, F(9.584632)=3.75, P<0>

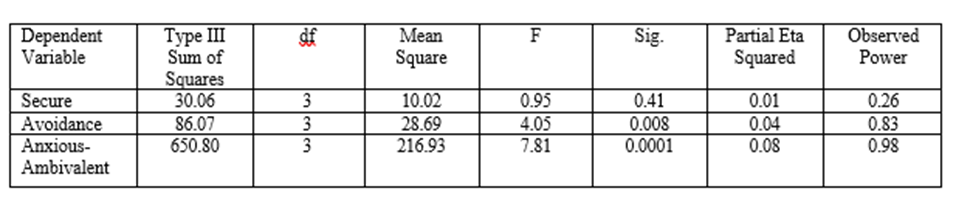

Table 5: One-way analysis of variance on attachment styles for difference between the groups

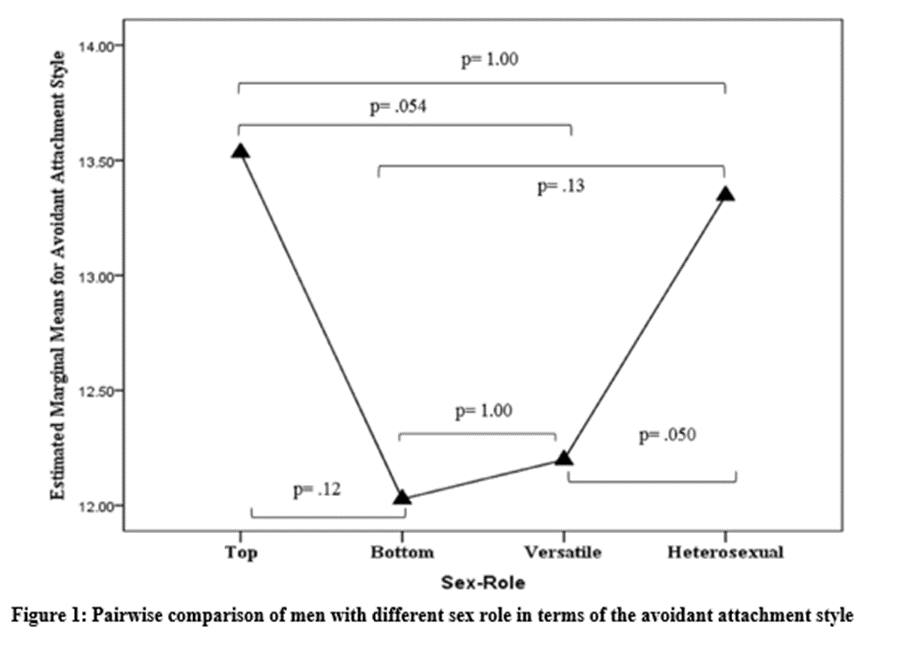

The data contained in Table 5 show that the F-statistic of avoidance style (4.05) and anxious-ambivalent style (7.81) were statistically significant at the 0.01 level. This means that there was a significant difference between the study groups in this attachment style. However, the F-statistic of secure attachment style (F= 0.95, P>0.05) was not statistically significant. Considering the effect size of the avoidance attunement style (η2= 0.04) and the anxious-ambivalent attachment style (η2= 0.08), it can be stated that the difference between the population members in these two attachment styles was at a moderate level. Figures 1 and 2 presents the results of pairwise comparisons between the studied groups in the mean scores of avoidant and anxious-ambivalent attachment styles.

According to the data presented in figures 1 and 2, the results of the Games-Howell post-hoc test were statistically significant for avoidant and anxious-ambivalent attachment styles. The results of this post-hoc test indicated that there was a significant difference between versatile gay men and heterosexual men in the avoidant attachment style. In addition, there was a significant difference between top, bottom, versatile gay men with the heterosexual men in terms of the anxious-ambivalent attachment style (P=0.02, P lessthan 0.001, and P lessthan 0.0001, respectively). However, the highest mean score was related to bottom and then versatile gay men.

The study findings revealed that there was a significant difference between versatile gay men and heterosexual men in the avoidance attachment style, as heterosexual men obtained higher mean scores. A high score on the avoidance attachment style means that one evaluates others as controller, hostile, and inattentive. Accordingly, such individuals do not find physical relationships and emotional intimacy soothing and have any curiosity about other people's psycho-inner world. Such people are self-sufficient, self-confident, and independent and do not make any requests for help and deal with anxiety by ignoring emotions in stressful situations. In fact, the more internally angry they are, the more socially isolated they will be. Based on the study results, the level of avoidant attachment style was lower in versatile gay men compared to heterosexual men. This is not consistent with the findings of Shenkman and Boss (2019) and Shenkman and Stein (2021) who reported a higher level of the avoidant attachment style in gay men compared to their heterosexual peers.In a qualitative study, Gil (2007) showed that the level of internalized homophobia was lower in versatile gay men than their peers who play the top role. Moreover, versatile gay men assumed that they were psychologically, emotionally, and sexually more flexible than their peers who play other roles (top and bottom). It is noteworthy that internalized homophobia actually refers to the misconceptions internalized by homosexuals. Such misconceptions are the result of living in a society that values only heteronormative standards and undervalues the experiences of people with different sexual orientations. This exposes such people to negative feelings about themselves and their sexual orientation and even makes them reject their sexual identity and orientation (Frost and Meyer, 2009; Herek and Mclemore, 2013).Since internalized homophobia has a significant relationship with self-esteem, emotional stability, and self-acceptance (Ross and Rosser, 1996; Rowen and Malcolm, 2003), the low level of internalized homophobia in versatile gay men can be attributed to their increased self-acceptance and self-esteem. Therefore, versatile gay men enjoy a higher level of mental health compared to their peers who play other sex roles. Since versatile gay men do not have stubborn preferences in their sexual behaviors and are more flexible than their peers playing other sexual roles (Hart, 2003), it can be assumed that this group of gay men has more opportunities to interact with the surrounding world, both sexually and socially, resulting in their higher flexibility and adaptation to societal adversity. Iran is a patriarchal society while Gilligan (2018) and Chu (2014) explain patriarchy as an order of living that privileges some men over men, for instance, straights over gays. In patriarchy, from a young age, men learn the codes of masculinity contingent on the suppression of empathy and hiding of their vulnerability necessary for claiming superiority, and by shielding their relational desires and sensitivities, they wish to become a part of the boys’ community. Otherwise, they would not be accepted due to being seen as girly or gay. In other words, there is the internalization of the masculine taboo on tenderness which encourages men to cover their emotional vulnerabilities. So, patriarchy has roots in the separation of the self from the relationship and paradoxically men have to sacrifice their relationships with self and emotions in order to have “relationships”. The price of acceptance into patriarchal order is “The Loss” and the only way to guarantee security toward it is by sacrificing the freedom of intimacy. Furthermore, in this world, being a man means being self-reliant, emotionally stoic, and independent. However, Bowlby's observation depicts that this independence not only isn’t manhood but also is a kind of detachment that can be mistaken for maturity, because it mirrors the pseudo-independent of manhood which in patriarchy is synonymous with being fully human. It can show why heterosexual groups achieve higher mean scores in avoidant attachment style in the current study. This study showed that there was a significant difference between gay men of all three sex roles (top, bottom, and versatile) and heterosexual men in the anxious-ambivalent attachment style. However, the gay men playing the bottom sex role obtained higher scores. The higher mean score of gay men of all three sex roles in the anxious-ambivalent attachment style compared to their heterosexual peers indicates that such individuals greatly need physical-emotional intimacy and usually experience a high level of anxiety in establishing and maintaining intimate relationships, while their relationships have no or negligible effect on reducing their anxiety. Members of this sexual minority are often in turmoil between approaching and avoiding and usually experience no two-way communication; such people experience a complex mix of negative emotions such as sadness, fear, self-criticism, and disability. This finding is consistent with the results of Nematy (2016) who reported the high level of the anxious-ambivalent attachment style in Iranian homosexual men and women and bisexuals compared to their heterosexual peers. However, this result is not consistent with the findings of Ridge (1998) who stated that there was no significant difference between homosexuals and heterosexuals in the frequency of attachment styles and also the findings of Mohr (2008) who reported that there was no significant difference between gay men and their heterosexual peers in attachment styles and intimate relationships. On the one hand, previous studies have shown that most of gay men exhibit greater childhood gender nonconformity than their heterosexual peers do, indicating the relative dominance of feminine behaviors over masculine behaviors. There is a correlation between gender nonconforming in gay men and a poor father-child relationship. The above-mentioned correlation can be attributed to the fact that it is difficult for fathers to accept the gender-nonconforming of their gay children. It should be noted that gay men are more likely than their heterosexual peers to be rejected by and isolated from their fathers in childhood. It is a factor that can independently predict the emergence of the anxious-ambivalent attachment style in adulthood (Bradley, 1989; Lytton, 1991; Bailey & Zucker, 1995; Beard & Bakeman, 2000; Landolt, 2004).Given that Iranian gay grow up in a society dominated by the traditional culture of patriarchy and based on the common parenting styles in Iranian society, parents especially fathers play a very important role in making major decisions about their children's lives and children may live with their parents until marriage or even middle age. So, Iranian gay men are more prone to parental rejection (Nematy, 2016). Under these circumstances, gender nonconformity can increases the chance of losing family support and leads to emerge the anxious attachment style in such people.

On the other hand, the early parent-child relationship is not the only source of information to determine the attachment style of gay men (Allan, 2018). The results of Landolt (2004) showed that the rejection of gender nonconforming children not only from their parents, but also from their peers can lead to the formation of the anxiety attachment style in adulthood. Gay men also have a strong desire to explore and nurture their identity in a social context that allows them the opportunity to do so. Community and peers can serve gay men as a caregiver who helps a child to develop a lovely and secure self. In addition to relationships with parents, relationships with peers can independently affect the attachment style of gay men. Childhood gender nonconformity can affect a gay man’s relationships with his peers. The boys who exhibit cross-gendered behaviors from early childhood are usually punished by their peers. Many gay men are brutally harassed because of this gender nonconformity; some of them have reported that they were usually rejected by their peers from childhood to adolescence. Moreover, peer rejection can mediate childhood gender nonconformity and the anxious attachment style. It can be hence concluded that gender nonconforming is closely related to anxiety in intimate relationships because it can lead to peer rejection and, thereby, increase the anxiety level (Saghir, 1973; Fagot, 1977; Landolt, 2004; Allan, 2018).In another study conducted by Sherry (2007), it was shown that the preoccupied-fearful (anxious-ambivalent) attachment style exhibited the strongest relationship with internalized homophobia, resulting in poor communication performance, less satisfaction with relationships, and establishment of less intimate relationships. In Iranian patriarchal culture, the male gender is manifested by two rules: (1) A man must be attracted to the opposite sex, and (2) a man must be homophobic (Eslen-Ziya, 2016). Furthermore, this culture not only relates masculinity to the exhibition of behaviors conforming to gender-specific stereotypes but also considers a lower social position for women than men. So, Iranian gay men are perceived more feminine and are accused of being “less of a man.” To compensate for this social view, gay men internalize homophobic behaviors, such as negative feelings towards their feminine side and that of the other gay men, to create a safe haven for their masculinity. The imitation of the generally accepted masculinity criteria by Iranian gay men in an attempt to avoid rejection from parent and peers increases their anxiety levels and leads to the emergence of the anxious attachment style in them.

Research limitations and recommendations

The main strength of this study was that it was the first research about the comparison of gay men playing different sex roles with their heterosexual peers in attachment styles. However, due to the methodological and theoretical limitations, the study findings should be generalized very cautiously. The first research limitation was non-random sampling; due to the existing social, cultural, and political conditions of Iran regarding issues related to sexual minorities, it is almost impossible to use random sampling in this sexual minority. The second research limitation was that an online questionnaire was used to collect data in order to ensure the safety of the participants; considering the great fear of the members of this sexual minority about being identified and punished, those who have filled out and sent the questionnaire probably enjoy specific personal features such as higher educational attainment, better socioeconomic status, higher levels of self-disclosure, and less avoidance. This is a hypothesis that needs to be further examined in the future. The third research limitation was related to online surveys in the above-mentioned apps (i.e. Hornet, Telegram, WhatsApp, and Instagram); the false self-expression of people about their sexual orientation and identity in cyberspace may affect the study results. This is especially true for people who introduce themselves as full-top. However, a preliminary interview was conducted in this study to identify non-false profiles to increase the accuracy of the results. Since the author used the Internet and dating software applications for purposive sampling, the study sample included only a small proportion of people belonging to this sexual minority, and it was not possible to access a large number of gay men who were not active in social networks for various reasons such as old age or lack of Internet access. The demographic questionnaire used in this study for self-label sex roles did not include options for identifying and separating versatile-top and versatile-bottom gay men. Therefore, these two groups of gay men were categorized as a single group named “versatile”. However, future studies are recommended to develop a measurement tool to classify and prioritize different sex roles of gay men. This study opens the door for a number future exploration. For instance, comparing parent-child relationship of three main sex roles of gay men with heterosexual men. Furthermore, comparing internalized homophobia of three main sex roles of gay men in different populations and various religions. Finally, comparing psychological flexibility of three main sex roles of gay men in different populations and in comparison, with heterosexual men.

Acknowledgments

This paper was extracted from a certified master's thesis presented by Seyed Mohsen Pourmohseni Shakib at the University of Guilan (No. 136292, January 12, 2021). The authors would like to thank all the participants who helped us in this research.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. This study did not receive any funding.

Disclosure statement

No financial interest or benefit was derived from the application of this research

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Council of postgraduate courses at university of Guilan (No. 136292, January 12, 2021) and the Local Research Ethics Committees. Informed consent was obtained from the participants.

Clearly Auctoresonline and particularly Psychology and Mental Health Care Journal is dedicated to improving health care services for individuals and populations. The editorial boards' ability to efficiently recognize and share the global importance of health literacy with a variety of stakeholders. Auctoresonline publishing platform can be used to facilitate of optimal client-based services and should be added to health care professionals' repertoire of evidence-based health care resources.

Journal of Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Intervention The submission and review process was adequate. However I think that the publication total value should have been enlightened in early fases. Thank you for all.

Journal of Women Health Care and Issues By the present mail, I want to say thank to you and tour colleagues for facilitating my published article. Specially thank you for the peer review process, support from the editorial office. I appreciate positively the quality of your journal.

Journal of Clinical Research and Reports I would be very delighted to submit my testimonial regarding the reviewer board and the editorial office. The reviewer board were accurate and helpful regarding any modifications for my manuscript. And the editorial office were very helpful and supportive in contacting and monitoring with any update and offering help. It was my pleasure to contribute with your promising Journal and I am looking forward for more collaboration.

We would like to thank the Journal of Thoracic Disease and Cardiothoracic Surgery because of the services they provided us for our articles. The peer-review process was done in a very excellent time manner, and the opinions of the reviewers helped us to improve our manuscript further. The editorial office had an outstanding correspondence with us and guided us in many ways. During a hard time of the pandemic that is affecting every one of us tremendously, the editorial office helped us make everything easier for publishing scientific work. Hope for a more scientific relationship with your Journal.

The peer-review process which consisted high quality queries on the paper. I did answer six reviewers’ questions and comments before the paper was accepted. The support from the editorial office is excellent.

Journal of Neuroscience and Neurological Surgery. I had the experience of publishing a research article recently. The whole process was simple from submission to publication. The reviewers made specific and valuable recommendations and corrections that improved the quality of my publication. I strongly recommend this Journal.

Dr. Katarzyna Byczkowska My testimonial covering: "The peer review process is quick and effective. The support from the editorial office is very professional and friendly. Quality of the Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions is scientific and publishes ground-breaking research on cardiology that is useful for other professionals in the field.

Thank you most sincerely, with regard to the support you have given in relation to the reviewing process and the processing of my article entitled "Large Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of The Prostate Gland: A Review and Update" for publication in your esteemed Journal, Journal of Cancer Research and Cellular Therapeutics". The editorial team has been very supportive.

Testimony of Journal of Clinical Otorhinolaryngology: work with your Reviews has been a educational and constructive experience. The editorial office were very helpful and supportive. It was a pleasure to contribute to your Journal.

Dr. Bernard Terkimbi Utoo, I am happy to publish my scientific work in Journal of Women Health Care and Issues (JWHCI). The manuscript submission was seamless and peer review process was top notch. I was amazed that 4 reviewers worked on the manuscript which made it a highly technical, standard and excellent quality paper. I appreciate the format and consideration for the APC as well as the speed of publication. It is my pleasure to continue with this scientific relationship with the esteem JWHCI.

This is an acknowledgment for peer reviewers, editorial board of Journal of Clinical Research and Reports. They show a lot of consideration for us as publishers for our research article “Evaluation of the different factors associated with side effects of COVID-19 vaccination on medical students, Mutah university, Al-Karak, Jordan”, in a very professional and easy way. This journal is one of outstanding medical journal.

Dear Hao Jiang, to Journal of Nutrition and Food Processing We greatly appreciate the efficient, professional and rapid processing of our paper by your team. If there is anything else we should do, please do not hesitate to let us know. On behalf of my co-authors, we would like to express our great appreciation to editor and reviewers.

As an author who has recently published in the journal "Brain and Neurological Disorders". I am delighted to provide a testimonial on the peer review process, editorial office support, and the overall quality of the journal. The peer review process at Brain and Neurological Disorders is rigorous and meticulous, ensuring that only high-quality, evidence-based research is published. The reviewers are experts in their fields, and their comments and suggestions were constructive and helped improve the quality of my manuscript. The review process was timely and efficient, with clear communication from the editorial office at each stage. The support from the editorial office was exceptional throughout the entire process. The editorial staff was responsive, professional, and always willing to help. They provided valuable guidance on formatting, structure, and ethical considerations, making the submission process seamless. Moreover, they kept me informed about the status of my manuscript and provided timely updates, which made the process less stressful. The journal Brain and Neurological Disorders is of the highest quality, with a strong focus on publishing cutting-edge research in the field of neurology. The articles published in this journal are well-researched, rigorously peer-reviewed, and written by experts in the field. The journal maintains high standards, ensuring that readers are provided with the most up-to-date and reliable information on brain and neurological disorders. In conclusion, I had a wonderful experience publishing in Brain and Neurological Disorders. The peer review process was thorough, the editorial office provided exceptional support, and the journal's quality is second to none. I would highly recommend this journal to any researcher working in the field of neurology and brain disorders.

Dear Agrippa Hilda, Journal of Neuroscience and Neurological Surgery, Editorial Coordinator, I trust this message finds you well. I want to extend my appreciation for considering my article for publication in your esteemed journal. I am pleased to provide a testimonial regarding the peer review process and the support received from your editorial office. The peer review process for my paper was carried out in a highly professional and thorough manner. The feedback and comments provided by the authors were constructive and very useful in improving the quality of the manuscript. This rigorous assessment process undoubtedly contributes to the high standards maintained by your journal.

International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews. I strongly recommend to consider submitting your work to this high-quality journal. The support and availability of the Editorial staff is outstanding and the review process was both efficient and rigorous.

Thank you very much for publishing my Research Article titled “Comparing Treatment Outcome Of Allergic Rhinitis Patients After Using Fluticasone Nasal Spray And Nasal Douching" in the Journal of Clinical Otorhinolaryngology. As Medical Professionals we are immensely benefited from study of various informative Articles and Papers published in this high quality Journal. I look forward to enriching my knowledge by regular study of the Journal and contribute my future work in the field of ENT through the Journal for use by the medical fraternity. The support from the Editorial office was excellent and very prompt. I also welcome the comments received from the readers of my Research Article.

Dear Erica Kelsey, Editorial Coordinator of Cancer Research and Cellular Therapeutics Our team is very satisfied with the processing of our paper by your journal. That was fast, efficient, rigorous, but without unnecessary complications. We appreciated the very short time between the submission of the paper and its publication on line on your site.

I am very glad to say that the peer review process is very successful and fast and support from the Editorial Office. Therefore, I would like to continue our scientific relationship for a long time. And I especially thank you for your kindly attention towards my article. Have a good day!

"We recently published an article entitled “Influence of beta-Cyclodextrins upon the Degradation of Carbofuran Derivatives under Alkaline Conditions" in the Journal of “Pesticides and Biofertilizers” to show that the cyclodextrins protect the carbamates increasing their half-life time in the presence of basic conditions This will be very helpful to understand carbofuran behaviour in the analytical, agro-environmental and food areas. We greatly appreciated the interaction with the editor and the editorial team; we were particularly well accompanied during the course of the revision process, since all various steps towards publication were short and without delay".

I would like to express my gratitude towards you process of article review and submission. I found this to be very fair and expedient. Your follow up has been excellent. I have many publications in national and international journal and your process has been one of the best so far. Keep up the great work.

We are grateful for this opportunity to provide a glowing recommendation to the Journal of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy. We found that the editorial team were very supportive, helpful, kept us abreast of timelines and over all very professional in nature. The peer review process was rigorous, efficient and constructive that really enhanced our article submission. The experience with this journal remains one of our best ever and we look forward to providing future submissions in the near future.

I am very pleased to serve as EBM of the journal, I hope many years of my experience in stem cells can help the journal from one way or another. As we know, stem cells hold great potential for regenerative medicine, which are mostly used to promote the repair response of diseased, dysfunctional or injured tissue using stem cells or their derivatives. I think Stem Cell Research and Therapeutics International is a great platform to publish and share the understanding towards the biology and translational or clinical application of stem cells.

I would like to give my testimony in the support I have got by the peer review process and to support the editorial office where they were of asset to support young author like me to be encouraged to publish their work in your respected journal and globalize and share knowledge across the globe. I really give my great gratitude to your journal and the peer review including the editorial office.

I am delighted to publish our manuscript entitled "A Perspective on Cocaine Induced Stroke - Its Mechanisms and Management" in the Journal of Neuroscience and Neurological Surgery. The peer review process, support from the editorial office, and quality of the journal are excellent. The manuscripts published are of high quality and of excellent scientific value. I recommend this journal very much to colleagues.

Dr.Tania Muñoz, My experience as researcher and author of a review article in The Journal Clinical Cardiology and Interventions has been very enriching and stimulating. The editorial team is excellent, performs its work with absolute responsibility and delivery. They are proactive, dynamic and receptive to all proposals. Supporting at all times the vast universe of authors who choose them as an option for publication. The team of review specialists, members of the editorial board, are brilliant professionals, with remarkable performance in medical research and scientific methodology. Together they form a frontline team that consolidates the JCCI as a magnificent option for the publication and review of high-level medical articles and broad collective interest. I am honored to be able to share my review article and open to receive all your comments.

“The peer review process of JPMHC is quick and effective. Authors are benefited by good and professional reviewers with huge experience in the field of psychology and mental health. The support from the editorial office is very professional. People to contact to are friendly and happy to help and assist any query authors might have. Quality of the Journal is scientific and publishes ground-breaking research on mental health that is useful for other professionals in the field”.

Dear editorial department: On behalf of our team, I hereby certify the reliability and superiority of the International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews in the peer review process, editorial support, and journal quality. Firstly, the peer review process of the International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews is rigorous, fair, transparent, fast, and of high quality. The editorial department invites experts from relevant fields as anonymous reviewers to review all submitted manuscripts. These experts have rich academic backgrounds and experience, and can accurately evaluate the academic quality, originality, and suitability of manuscripts. The editorial department is committed to ensuring the rigor of the peer review process, while also making every effort to ensure a fast review cycle to meet the needs of authors and the academic community. Secondly, the editorial team of the International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews is composed of a group of senior scholars and professionals with rich experience and professional knowledge in related fields. The editorial department is committed to assisting authors in improving their manuscripts, ensuring their academic accuracy, clarity, and completeness. Editors actively collaborate with authors, providing useful suggestions and feedback to promote the improvement and development of the manuscript. We believe that the support of the editorial department is one of the key factors in ensuring the quality of the journal. Finally, the International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews is renowned for its high- quality articles and strict academic standards. The editorial department is committed to publishing innovative and academically valuable research results to promote the development and progress of related fields. The International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews is reasonably priced and ensures excellent service and quality ratio, allowing authors to obtain high-level academic publishing opportunities in an affordable manner. I hereby solemnly declare that the International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews has a high level of credibility and superiority in terms of peer review process, editorial support, reasonable fees, and journal quality. Sincerely, Rui Tao.

Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions I testity the covering of the peer review process, support from the editorial office, and quality of the journal.

Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions, we deeply appreciate the interest shown in our work and its publication. It has been a true pleasure to collaborate with you. The peer review process, as well as the support provided by the editorial office, have been exceptional, and the quality of the journal is very high, which was a determining factor in our decision to publish with you.

The peer reviewers process is quick and effective, the supports from editorial office is excellent, the quality of journal is high. I would like to collabroate with Internatioanl journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews journal clinically in the future time.

Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions, I would like to express my sincerest gratitude for the trust placed in our team for the publication in your journal. It has been a true pleasure to collaborate with you on this project. I am pleased to inform you that both the peer review process and the attention from the editorial coordination have been excellent. Your team has worked with dedication and professionalism to ensure that your publication meets the highest standards of quality. We are confident that this collaboration will result in mutual success, and we are eager to see the fruits of this shared effort.

Dear Dr. Jessica Magne, Editorial Coordinator 0f Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions, I hope this message finds you well. I want to express my utmost gratitude for your excellent work and for the dedication and speed in the publication process of my article titled "Navigating Innovation: Qualitative Insights on Using Technology for Health Education in Acute Coronary Syndrome Patients." I am very satisfied with the peer review process, the support from the editorial office, and the quality of the journal. I hope we can maintain our scientific relationship in the long term.

Dear Monica Gissare, - Editorial Coordinator of Nutrition and Food Processing. ¨My testimony with you is truly professional, with a positive response regarding the follow-up of the article and its review, you took into account my qualities and the importance of the topic¨.

Dear Dr. Jessica Magne, Editorial Coordinator 0f Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions, The review process for the article “The Handling of Anti-aggregants and Anticoagulants in the Oncologic Heart Patient Submitted to Surgery” was extremely rigorous and detailed. From the initial submission to the final acceptance, the editorial team at the “Journal of Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions” demonstrated a high level of professionalism and dedication. The reviewers provided constructive and detailed feedback, which was essential for improving the quality of our work. Communication was always clear and efficient, ensuring that all our questions were promptly addressed. The quality of the “Journal of Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions” is undeniable. It is a peer-reviewed, open-access publication dedicated exclusively to disseminating high-quality research in the field of clinical cardiology and cardiovascular interventions. The journal's impact factor is currently under evaluation, and it is indexed in reputable databases, which further reinforces its credibility and relevance in the scientific field. I highly recommend this journal to researchers looking for a reputable platform to publish their studies.

Dear Editorial Coordinator of the Journal of Nutrition and Food Processing! "I would like to thank the Journal of Nutrition and Food Processing for including and publishing my article. The peer review process was very quick, movement and precise. The Editorial Board has done an extremely conscientious job with much help, valuable comments and advices. I find the journal very valuable from a professional point of view, thank you very much for allowing me to be part of it and I would like to participate in the future!”

Dealing with The Journal of Neurology and Neurological Surgery was very smooth and comprehensive. The office staff took time to address my needs and the response from editors and the office was prompt and fair. I certainly hope to publish with this journal again.Their professionalism is apparent and more than satisfactory. Susan Weiner

My Testimonial Covering as fellowing: Lin-Show Chin. The peer reviewers process is quick and effective, the supports from editorial office is excellent, the quality of journal is high. I would like to collabroate with Internatioanl journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews.

My experience publishing in Psychology and Mental Health Care was exceptional. The peer review process was rigorous and constructive, with reviewers providing valuable insights that helped enhance the quality of our work. The editorial team was highly supportive and responsive, making the submission process smooth and efficient. The journal's commitment to high standards and academic rigor makes it a respected platform for quality research. I am grateful for the opportunity to publish in such a reputable journal.

My experience publishing in International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews was exceptional. I Come forth to Provide a Testimonial Covering the Peer Review Process and the editorial office for the Professional and Impartial Evaluation of the Manuscript.

I would like to offer my testimony in the support. I have received through the peer review process and support the editorial office where they are to support young authors like me, encourage them to publish their work in your esteemed journals, and globalize and share knowledge globally. I really appreciate your journal, peer review, and editorial office.

Dear Agrippa Hilda- Editorial Coordinator of Journal of Neuroscience and Neurological Surgery, "The peer review process was very quick and of high quality, which can also be seen in the articles in the journal. The collaboration with the editorial office was very good."

I would like to express my sincere gratitude for the support and efficiency provided by the editorial office throughout the publication process of my article, “Delayed Vulvar Metastases from Rectal Carcinoma: A Case Report.” I greatly appreciate the assistance and guidance I received from your team, which made the entire process smooth and efficient. The peer review process was thorough and constructive, contributing to the overall quality of the final article. I am very grateful for the high level of professionalism and commitment shown by the editorial staff, and I look forward to maintaining a long-term collaboration with the International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews.

To Dear Erin Aust, I would like to express my heartfelt appreciation for the opportunity to have my work published in this esteemed journal. The entire publication process was smooth and well-organized, and I am extremely satisfied with the final result. The Editorial Team demonstrated the utmost professionalism, providing prompt and insightful feedback throughout the review process. Their clear communication and constructive suggestions were invaluable in enhancing my manuscript, and their meticulous attention to detail and dedication to quality are truly commendable. Additionally, the support from the Editorial Office was exceptional. From the initial submission to the final publication, I was guided through every step of the process with great care and professionalism. The team's responsiveness and assistance made the entire experience both easy and stress-free. I am also deeply impressed by the quality and reputation of the journal. It is an honor to have my research featured in such a respected publication, and I am confident that it will make a meaningful contribution to the field.

"I am grateful for the opportunity of contributing to [International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews] and for the rigorous review process that enhances the quality of research published in your esteemed journal. I sincerely appreciate the time and effort of your team who have dedicatedly helped me in improvising changes and modifying my manuscript. The insightful comments and constructive feedback provided have been invaluable in refining and strengthening my work".

I thank the ‘Journal of Clinical Research and Reports’ for accepting this article for publication. This is a rigorously peer reviewed journal which is on all major global scientific data bases. I note the review process was prompt, thorough and professionally critical. It gave us an insight into a number of important scientific/statistical issues. The review prompted us to review the relevant literature again and look at the limitations of the study. The peer reviewers were open, clear in the instructions and the editorial team was very prompt in their communication. This journal certainly publishes quality research articles. I would recommend the journal for any future publications.

Dear Jessica Magne, with gratitude for the joint work. Fast process of receiving and processing the submitted scientific materials in “Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions”. High level of competence of the editors with clear and correct recommendations and ideas for enriching the article.

We found the peer review process quick and positive in its input. The support from the editorial officer has been very agile, always with the intention of improving the article and taking into account our subsequent corrections.

My article, titled 'No Way Out of the Smartphone Epidemic Without Considering the Insights of Brain Research,' has been republished in the International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews. The review process was seamless and professional, with the editors being both friendly and supportive. I am deeply grateful for their efforts.

To Dear Erin Aust – Editorial Coordinator of Journal of General Medicine and Clinical Practice! I declare that I am absolutely satisfied with your work carried out with great competence in following the manuscript during the various stages from its receipt, during the revision process to the final acceptance for publication. Thank Prof. Elvira Farina

Dear Jessica, and the super professional team of the ‘Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions’ I am sincerely grateful to the coordinated work of the journal team for the no problem with the submission of my manuscript: “Cardiometabolic Disorders in A Pregnant Woman with Severe Preeclampsia on the Background of Morbid Obesity (Case Report).” The review process by 5 experts was fast, and the comments were professional, which made it more specific and academic, and the process of publication and presentation of the article was excellent. I recommend that my colleagues publish articles in this journal, and I am interested in further scientific cooperation. Sincerely and best wishes, Dr. Oleg Golyanovskiy.

Dear Ashley Rosa, Editorial Coordinator of the journal - Psychology and Mental Health Care. " The process of obtaining publication of my article in the Psychology and Mental Health Journal was positive in all areas. The peer review process resulted in a number of valuable comments, the editorial process was collaborative and timely, and the quality of this journal has been quickly noticed, resulting in alternative journals contacting me to publish with them." Warm regards, Susan Anne Smith, PhD. Australian Breastfeeding Association.

Dear Jessica Magne, Editorial Coordinator, Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions, Auctores Publishing LLC. I appreciate the journal (JCCI) editorial office support, the entire team leads were always ready to help, not only on technical front but also on thorough process. Also, I should thank dear reviewers’ attention to detail and creative approach to teach me and bring new insights by their comments. Surely, more discussions and introduction of other hemodynamic devices would provide better prevention and management of shock states. Your efforts and dedication in presenting educational materials in this journal are commendable. Best wishes from, Farahnaz Fallahian.

Dear Maria Emerson, Editorial Coordinator, International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews, Auctores Publishing LLC. I am delighted to have published our manuscript, "Acute Colonic Pseudo-Obstruction (ACPO): A rare but serious complication following caesarean section." I want to thank the editorial team, especially Maria Emerson, for their prompt review of the manuscript, quick responses to queries, and overall support. Yours sincerely Dr. Victor Olagundoye.

Dear Ashley Rosa, Editorial Coordinator, International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews. Many thanks for publishing this manuscript after I lost confidence the editors were most helpful, more than other journals Best wishes from, Susan Anne Smith, PhD. Australian Breastfeeding Association.

Dear Agrippa Hilda, Editorial Coordinator, Journal of Neuroscience and Neurological Surgery. The entire process including article submission, review, revision, and publication was extremely easy. The journal editor was prompt and helpful, and the reviewers contributed to the quality of the paper. Thank you so much! Eric Nussbaum, MD

Dr Hala Al Shaikh This is to acknowledge that the peer review process for the article ’ A Novel Gnrh1 Gene Mutation in Four Omani Male Siblings, Presentation and Management ’ sent to the International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews was quick and smooth. The editorial office was prompt with easy communication.

Dear Erin Aust, Editorial Coordinator, Journal of General Medicine and Clinical Practice. We are pleased to share our experience with the “Journal of General Medicine and Clinical Practice”, following the successful publication of our article. The peer review process was thorough and constructive, helping to improve the clarity and quality of the manuscript. We are especially thankful to Ms. Erin Aust, the Editorial Coordinator, for her prompt communication and continuous support throughout the process. Her professionalism ensured a smooth and efficient publication experience. The journal upholds high editorial standards, and we highly recommend it to fellow researchers seeking a credible platform for their work. Best wishes By, Dr. Rakhi Mishra.

Dear Jessica Magne, Editorial Coordinator, Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions, Auctores Publishing LLC. The peer review process of the journal of Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions was excellent and fast, as was the support of the editorial office and the quality of the journal. Kind regards Walter F. Riesen Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. Walter F. Riesen.

Dear Ashley Rosa, Editorial Coordinator, International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews, Auctores Publishing LLC. Thank you for publishing our article, Exploring Clozapine's Efficacy in Managing Aggression: A Multiple Single-Case Study in Forensic Psychiatry in the international journal of clinical case reports and reviews. We found the peer review process very professional and efficient. The comments were constructive, and the whole process was efficient. On behalf of the co-authors, I would like to thank you for publishing this article. With regards, Dr. Jelle R. Lettinga.

Dear Clarissa Eric, Editorial Coordinator, Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Studies, I would like to express my deep admiration for the exceptional professionalism demonstrated by your journal. I am thoroughly impressed by the speed of the editorial process, the substantive and insightful reviews, and the meticulous preparation of the manuscript for publication. Additionally, I greatly appreciate the courteous and immediate responses from your editorial office to all my inquiries. Best Regards, Dariusz Ziora

Dear Chrystine Mejia, Editorial Coordinator, Journal of Neurodegeneration and Neurorehabilitation, Auctores Publishing LLC, We would like to thank the editorial team for the smooth and high-quality communication leading up to the publication of our article in the Journal of Neurodegeneration and Neurorehabilitation. The reviewers have extensive knowledge in the field, and their relevant questions helped to add value to our publication. Kind regards, Dr. Ravi Shrivastava.

Dear Clarissa Eric, Editorial Coordinator, Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Studies, Auctores Publishing LLC, USA Office: +1-(302)-520-2644. I would like to express my sincere appreciation for the efficient and professional handling of my case report by the ‘Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Studies’. The peer review process was not only fast but also highly constructive—the reviewers’ comments were clear, relevant, and greatly helped me improve the quality and clarity of my manuscript. I also received excellent support from the editorial office throughout the process. Communication was smooth and timely, and I felt well guided at every stage, from submission to publication. The overall quality and rigor of the journal are truly commendable. I am pleased to have published my work with Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Studies, and I look forward to future opportunities for collaboration. Sincerely, Aline Tollet, UCLouvain.

Dear Ms. Mayra Duenas, Editorial Coordinator, International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews. “The International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews represented the “ideal house” to share with the research community a first experience with the use of the Simeox device for speech rehabilitation. High scientific reputation and attractive website communication were first determinants for the selection of this Journal, and the following submission process exceeded expectations: fast but highly professional peer review, great support by the editorial office, elegant graphic layout. Exactly what a dynamic research team - also composed by allied professionals - needs!" From, Chiara Beccaluva, PT - Italy.

Dear Maria Emerson, Editorial Coordinator, we have deeply appreciated the professionalism demonstrated by the International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Reviews. The reviewers have extensive knowledge of our field and have been very efficient and fast in supporting the process. I am really looking forward to further collaboration. Thanks. Best regards, Dr. Claudio Ligresti